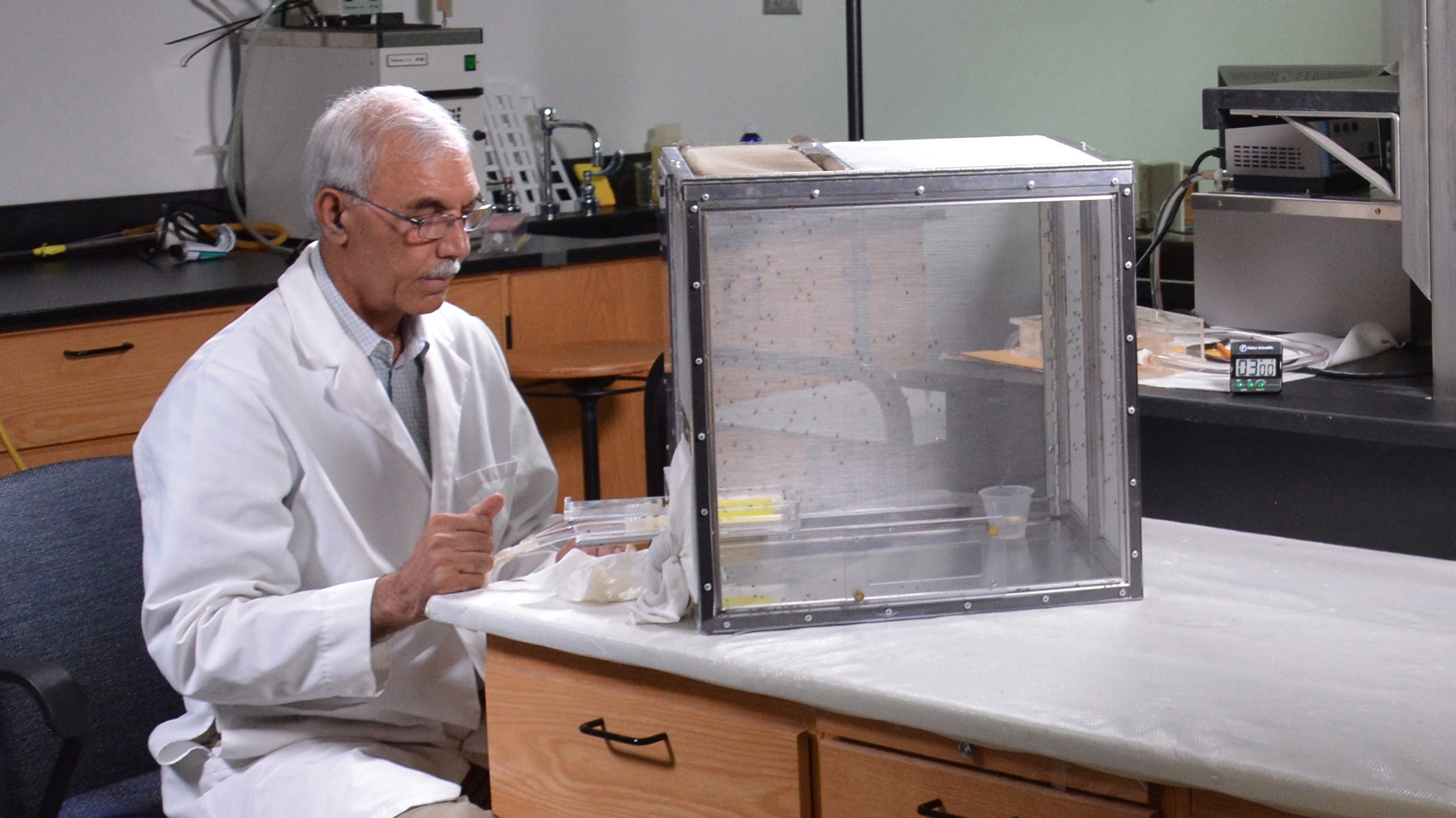

Abbas Ali, a principal scientist in the UM National Center for Natural Products Research, works to develop insect repellents from natural products, part of the School of Pharmacy's efforts to fight diseases transmitted by the insects. Photo by Sydney Slotkin DuPriest/School of Pharmacy

Latest development in University of Mississippi search for natural products with repellent properties

A flowering plant may provide a safe, biodegradable replacement for DEET as a primary insect repellent.

Researchers at the University of Mississippi‘s National Center for Natural Products Research have published a paper in the journal Molecules demonstrating that Stenaria nigricans contains compounds that repel mosquitos.

The study is the latest development in an ongoing, long-term partnership between the NCNPR, housed in the School of Pharmacy, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to screen natural products for a variety of potential uses in the areas of health and agriculture.

“There is very little information about the use of natural products in insect management, so that’s what we have set out to do,” said Ikhlas Khan, NCNPR director. “We are looking for natural sources that have compounds or molecules that have the potential to repel insects like mosquitoes and fire ants. Everyone is looking for natural remedies to take care of these problems.”

Stenaria nigricans, a perennial commonly known as bluet or diamond flower, produces small white or pale-lavender flowers with four petals arranged in a diamondlike pattern.

While NCNPR researchers often investigate natural products through ethnobotany, or the study of indigenous plants that are used by different cultures, Stenaria nigricans was flagged as part of a random screening of hundreds of plants for repellent activity against mosquitos and fire ants.

Mosquito repellency is particularly important on a global scale, since these insects can transmit diseases such as malaria, West Nile virus, yellow fever and encephalitis.

The samples used in NCNPR screens often come from the center’s repository of more than 18,000 natural product specimens. Abbas Ali, principal scientist at the NCNPR, has tested thousands of these samples during his 14 years at the center.

“Initial screening for mosquito repellency is conducted using a bioassay (biological assay) system that exposes female mosquitoes to compound-treated fabric in small chambers,” he said. “Females are used because they alone transmit disease when biting to feed. We record the landing and biting on the treated surface.

“If the test material is actively repellent, they will not land and feed.”

If a compound shows promise, it is then tested in another bioassay system that consists of a large cage where the mosquitos have the flexibility to move away from the repellent-treated surface. Finally, if the compound is active at this level, it is tested in a direct skin application bioassay by exposing a treated hand or arm in a cage.

The results show that compounds in Stenaria nigricans are very effective in repelling mosquitos.

Ali said it is important work because it supports the center’s mission to find compounds, extracts or essential oils that can be effectively used in practical situations. The benefits of natural insecticides as opposed to synthetic are great.

“With DEET, the chemical stays in place – degradation is very low,” he said. “We are working to find a safe and biodegradable natural compound to replace these chemicals.

“We have made great strides in identifying natural products that are equally effective and easily available.”

In 2022, the NCNPR team was awarded a U.S. patent for the use of carrot seed essential oil and its pure compound carotol as mosquito repellent. They are seeking a development and commercialization partner for this technology.

As for the diamond flower, further testing is needed to determine its practicality as a repellent, Khan said.

“Other studies will need to look at factors like the stability of the molecule, the availability of the molecule and whether it is economically feasible or not,” he said. “There’s a lot of research that has to happen beyond us, but we collaborate with other USDA labs that do this kind of work.

“After this, it could be considered a candidate for further development.”

The resources for this research were provided by grant “Toxicology, Chemical Ecology and Management of Invasive Ants,” funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Specific Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6066-1-025.

By Erin Garrett