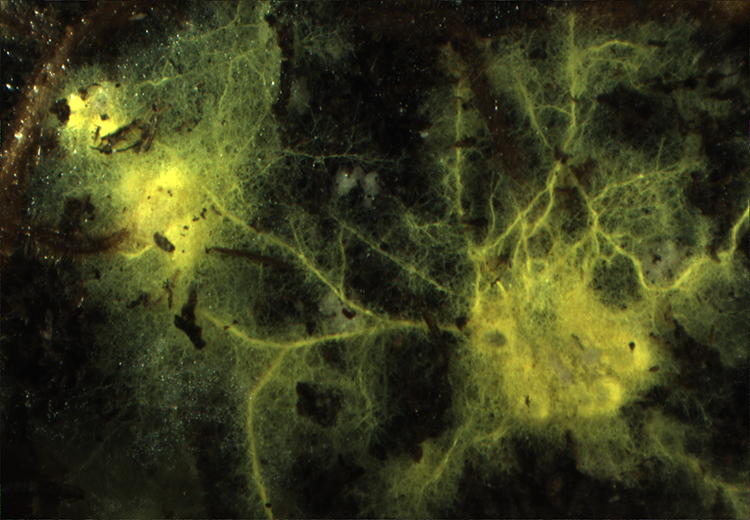

The Wood-Wide Web refers to network of fungi that connect roots of multiple plants of the same or different species underground, forming a common mycorrhizal network. Over the years, researchers have hypothesized that CMNs assist trees in providing resources to other trees, but a new study co-authored by University of Mississippi biologist Jason Hoeksema debunks that theory. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

University of Mississippi biology professor debunks popular theory about soil fungal networks

Imagine this: a tree in a forest is threatened by a predator or an invasive plant species. Underground, it sounds an alarm to neighboring trees through the “Wood-Wide Web,” a network of mycorrhizal fungi that connects them through the soil.

It is a fascinating theory, but a University of Mississippi scientist has doubts – and he’s published a paper that justifies them.

“Our paper investigates the science behind the idea that trees use common mycorrhizal networks to help redistribute resources and alter the balance of competitive interactions between them,” said Jason Hoeksema, professor of biology. “These ideas have grown really, really popular in recent years, particularly the idea that these connections are used by trees to help each other and even signal of enemies, danger or attack.”

The research – co-authored by Hoeksema; Justine Karst, first author and associate professor at the University of Alberta; and Melanie Jones, professor of biology at the University of British Columbia – was published February 13 as “Positive citation bias and overinterpreted results lead to misinformation on common mycorrhizal networks in forests” in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The Wood-Wide Web was coined in the late 1990s to refer to network of fungi that connect roots of multiple plants of the same or different species belowground, forming a common mycorrhizal network, or CMN. Over the years, researchers have hypothesized that CMNs assist trees, especially old and large ones, with providing resources to other trees.

The idea is so pervasive that it has been accepted as gospel among many scientists and in popular media as well. The subject has been featured in TED Talks, books, podcasts, documentaries, and even popped up in one of Hoeksema’s favorite television shows, “Ted Lasso.”

“As a society, we need to try to think critically when we see what seems like really convincing information on the internet, whether it’s a YouTube video, TikTok or documentary,” Hoeksema said. “If it seems too good to be true, and it’s not discussing possible alternatives, we should look at it skeptically.”

More than 25 years of research has been conducted, both in the lab and in the field, on mycorrhizal fungi networks and their relationship to trees. Hoeksema and his co-authors critically reviewed these studies for the strength of their evidence and how effectively the experiments were carried out.

The paper examines three main claims. The first is that common mycorrhizal networks are ubiquitous; they are everywhere and in a persistently functional state.

“We found that there are very few studies that find evidence of this in the field,” Hoeksema said. “Even if there is evidence that they form, which is likely, we don’t know if they last and whether they last long enough to be functional, because they may die frequently.”

The second claim the authors investigated is that CMNs are beneficial to the trees and forests. They found that these benefits were almost always tested in seedlings, not mature plants. While testing growth and survival on adult trees would be difficult, conclusions should not be drawn based on experiments with seedlings, Hoeksema said.

“Even in the studies on seedlings, only a small percentage of them show benefits for seedings to be connected to these networks,” he said. “Frequently those benefits are offset by negative effects that are happening at the same time.”

One such negative effect is mediated by roots when they are separated from the fungal networks during experimentation. This root competition would offset the benefits of the CMNs and allow for alternative explanations of the results. Hoeksema and his co-authors provide suggested approaches for experimentation going forward to eliminate this effect.

Some individuals advocate against clear-cutting old growth forests because of the purported benefits of CMNs. The paper concludes that knowledge on CMNs is too sparse and unsettled to inform forest management.

This does not negate the importance of mycorrhizal fungi to forest ecosystems, Karst said.

“Even if trees don’t ‘talk’ to one another through underground fungi, there are many reasons to be concerned about losing old growth forests,” Karst said. “While we don’t understand the function of common mycorrhizal networks in forests, we do know that mycorrhizal fungi are important to trees, soils, and forest ecosystems.

“Some of these fungi are essential for nutrient cycling and tree productivity, some aid trees in tolerance of stressors, and others promote carbon sequestration belowground.”

The third claim addressed in the paper is that trees warn one other of threats, such as insect damage, by signaling through the networks.

“We found the least evidence for this of all,” Hoeksema said. “There are no field studies that address this question and only one greenhouse study using seedlings in pots.”

That study is intriguing, but problematic, Hoeksema said. It showed signaling when seedlings in pots were connected only by CMNs and did not have overlapping roots. When the roots were allowed to interconnect, as they would in nature, the signaling was not present.

“We don’t understand why we would see the effect without roots, but when roots interact naturally the signaling goes away,” Hoeksema said. “It’s part of the fascination of forests and tree interactions and illustrates the mysteries that are out still there.”

Another component of the paper looks at a “disturbing” trend of inaccurate citations of influential scientific papers on the subject.

“Inaccurate citations were increasing over time during the last 25 years,” Hoeksema said. “It was to the point where, depending upon which part of the literature you look at, 25%-50% of the citations are now considered unsupported.

“This misinformation seems to be propagated through the scientific literature as well and growing.”

Karst said that science is not static and rarely “settled.”

“To many in the research community, that trees communicate through underground fungal networks was never settled,” she said. “It has recently been touted as an established fact, but this ignores a long-standing debate. It’s critical to scrutinize extraordinary claims because they can distort the science and mislead the public.

“As researchers in this field, we are obliged to call out misinformation; otherwise, science loses its credibility.”

Hoeksema agrees and hopes that the paper will “reset the field to some degree.”

“We want to encourage scientists and the next generation to look at these questions in a fresh way that doesn’t assume anything about the results,” he said. “Rather, to look at them critically and try to move forward while recognizing that we have fascinating complexities that need to be worked out.”

By Erin Garrett