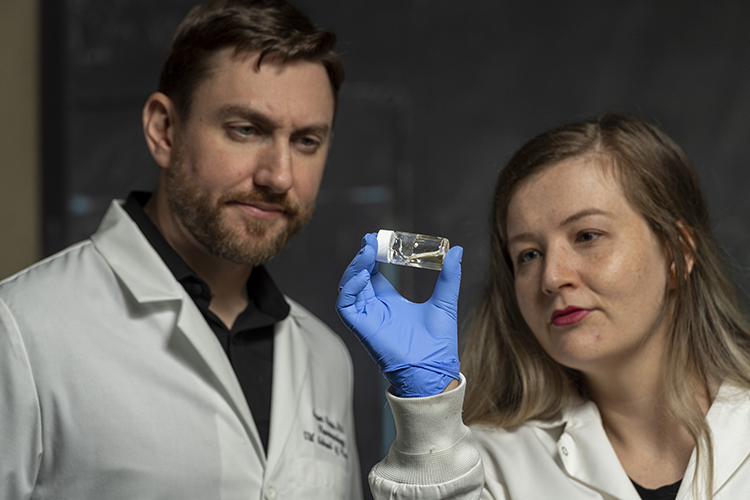

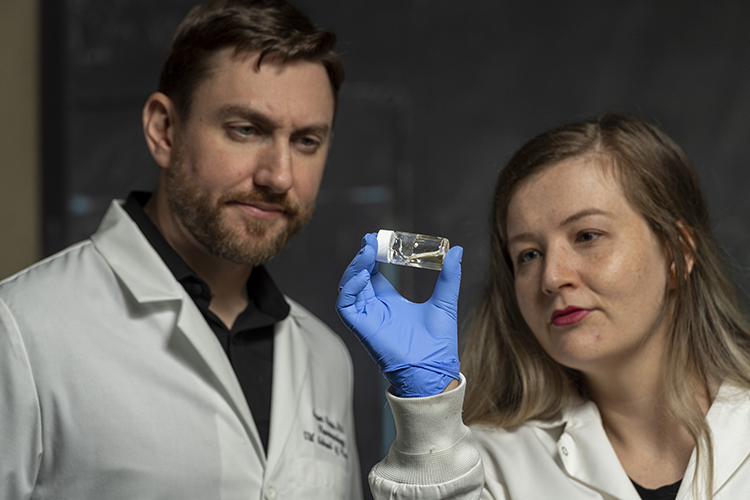

Eden Tanner (right), an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Mississippi, studies ionic liquids and their potential uses. She is working with Jason Paris, research associate professor of pharmacology, to coat nanoparticles with ionic liquids, allowing them to attach themselves to red blood cells. Once the red blood cells reach the brain, the nanoparticles self-destruct and release a drug. Photo by Srijita Chattopadhyay/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

Researchers use ‘body’s natural transport mechanisms’ to target the brain

University of Mississippi researchers are developing a novel treatment for the neurological complications of HIV, also known as neuro-HIV.

The National Institutes of Health awarded a five-year grant to Eden Tanner, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and Jason Paris, research associate professor of pharmacology, to support this work. The duo received $436,000 for the first year of the project.

Antiretroviral therapies, which are the only existing treatment for HIV, are unable to sufficiently accumulate in the brain to target infected cells there. This renders them largely useless against the neurological effects of HIV, which can be debilitating.

These effects, such as cognitive impairment, major depression and chronic pain, are intensified if the virus progresses to AIDS.

“Retroviral therapies can stop the virus from being replicated in the rest of the body, but we can’t get those drugs into the brain in therapeutic concentrations – essentially, this virus goes unimpeded into the brain,” Tanner said. “This causes worsening neurological deficits and affects a large percentage of the patient population. Currently, there’s nothing we can do for it.”

Tanner’s lab at Ole Miss uses a method that allows nanoparticles to “hitch a ride” on red blood cells. Once the red blood cells reach the brain, the nanoparticles are programmed to self-destruct and release a drug. Her research has proven the technique to be successful.

Paris has studied HIV since he was a postdoctoral researcher. After hearing Tanner give a presentation on her work, he approached her with an idea to use the technology developed in her lab for neuro-HIV treatment.

“Her talk was great, and she asked if anyone had a use for these ionic liquid-coated nanoparticles that could target certain immune cells found in blood,” Paris said. “I told her this could solve a major problem in HIV if we could load them with antiretrovirals and target them to the immune cells of the brain.”

Tanner said their innovative approach could have a significant impact on the delivery of these drugs to the brain.

“What’s really unique is that we’re kind of using the human body’s natural transport mechanisms rather than trying to fight with them to deliver these drugs,” Tanner said. “The material I develop is called ionic liquids. This is what sticks the nanoparticles to the red blood cells to make this possible.

“Fifty percent of the nanoparticles that we deliver in this manner make it into the brain. Normally we get 1% to 2%, so this is a really big increase in delivery efficacy. I like to think about our work as being a fancy FedEx where the parcel gets there half of the time.”

Promising early data led the university to invest in patent protection around the core technology as well as its use against HIV and other diseases.

“Now this support from NIH provides a critical step in garnering the data that will be necessary for the long-term plan of taking this technology to first in-human trials,” Paris said.

The planned studies, in collaboration with Tulane University and its National Primate Research Center, will fund the extensive safety and pharmacokinetic testing that aims to demonstrate the materials are not harmful.

“This is actually the most exciting thing I’ve done in my career so far,” Paris said. “If successful, it could be transformative. This grant, in particular, will take us all the way from cells in a dish up to rodent models all the way to nonhuman primates. It’s a completely translational grant.”

The possibilities that this project represents are exciting, Tanner said.

“The goal is to eventually begin human trials,” she said. “What I’m most excited about is the opportunity to provide help to this patient population who is often vulnerable in other ways as well.

“That’s something that me and the rest of the team really hope to accomplish – to develop technology that improves people’s quality of life.”

Research reported in this press release was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DA056875.

By Erin Garrett