Over the last twenty or so years there’s been a lot of talk about something called “closure”. In most cases it’s being used in the context of death, particularly tragic deaths like the mass shootings of innocents, especially children. It’s also used when someone goes missing and cannot be found. Recovery after a major disaster, natural or otherwise, is often called “closure”. Closure is supposed to free us from the pain of tragedy and allow us to move forward in our lives. I understand that, but being the picky person about language that I am, it bugs me.

My high school English teacher, Mrs. Corinne King Guild, may her memory be a blessing, was more of a stickler for the proper use of grammar than am I. She taught me the difference between the denotation and the connotation of words. That’s one of the things that sometimes can make me seem like a pain in the ass to be around. I have learned through the years, though, to keep my mouth shut—sometimes.

The primary connotation that I hear in the word “closure” has to do with finality. When I hear someone talk about getting closure after a dreadful experience, sometimes I get the feeling that they’re saying, “Let’s put this in a box, tie a ribbon around it, hide it in a closet, and move on.” If that helps them, so be it.

To me, use of the word “closure” in many cases can lead people to think, “Well, they caught the killer so now those poor people are set free from their pain.” I’ve got news for you: those “poor people” will never be free from their pain. If they successfully travel the path of grief and healing, things will get better and they will be able to find a new normal for their lives, but very few will be able to carry on without a hole in their heart and a pain in their soul. There will still be triggers for their grief that will bring the whole experience back to the surface. The pain might not be as intense. It might not come as often or last as long. But it’s still there.

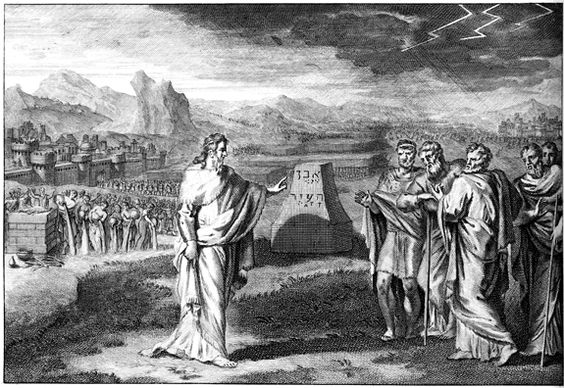

I am reminded of the Biblical story of the prophet Samuel as recorded in 1 Samuel 4-7. After years of warring, the Israelites defeated the Philistines. In commemoration, Samuel raised a great stone to G_d, naming it “Ebenezer”, meaning “Hitherto hath the LORD helped us.” The Stone of Help was a reminder of how G_d had helped them through their trials and troubles TO THAT POINT.

I submit that ofttimes when we use the word “closure” it more accurately is an Ebenezer—a recognition of having made it through another period of grief, growth, and recovery and a thanksgiving for the same.

Like peeling away the layers of an onion, every layer reduces the size of the onion and brings you that much closer to the core. Every layer of grief and pain that gets peeled away moves you to another chapter of your pain, but you give thanks for having gotten as far as you have. But then you find there’s another layer to face. Eventually you reach the center of the onion and there it is: the very thing that all those layers were covering up, and there you are, standing face-to-face with that which has broken you over and over and over again.

At that point true closure doesn’t consist of closure at all. It means fully embracing the pain of your loss, making a decision to give thanks for that which you once had, finding a safe place in your heart and soul to hold it, and keeping on keeping on in a way that honors your loss, not closed to the pain, but courageously open to the reality that one cannot love without the probability of loss.

What Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote in his poem In Memoriam AHH, 1850, I believe to be true: Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all.

Therefore, Here I raise my Ebenezer; / hither by Thy help I’m come.*

…and that’s the View from The Balcony.

Randy Weeks is a Licensed Professional Counselor, a Certified Shamanic Life Coach, an ordained minister, a singer-songwriter, and an actor. He is well-acquainted with the experiences of love, loss, grief, and healing. Randy may be reached at randallsweeks@gmail.com

*Come, thou Fount of every blessing, Author: Robert Robinson, (1758); Alterer: Martin Madan (1760)