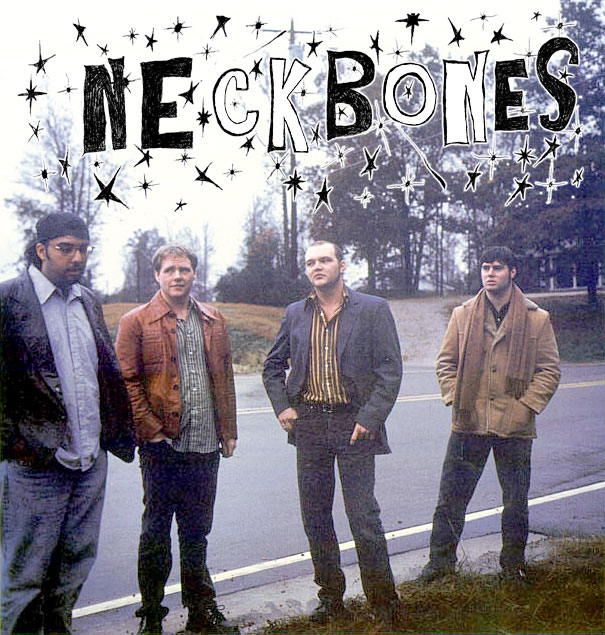

The Neckbones

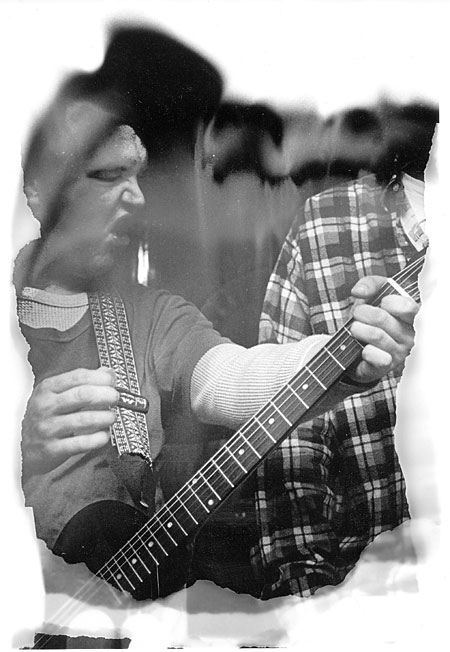

Interview and most photographs

by Newt Rayburn

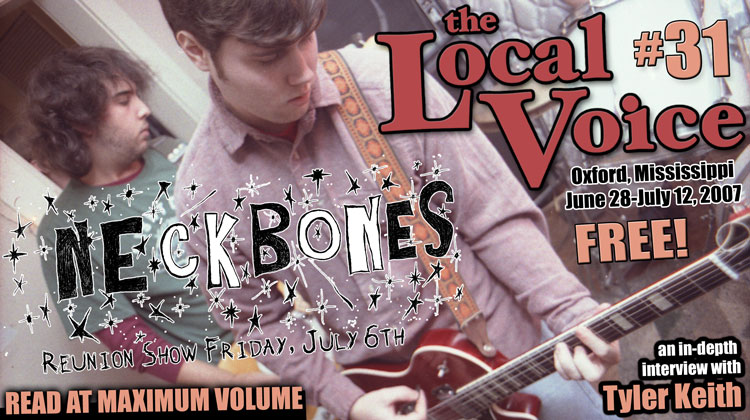

from The Local Voice #31

from The Local Voice #31

June 28, 2007

Download The Local Voice #31 PDF 99¢

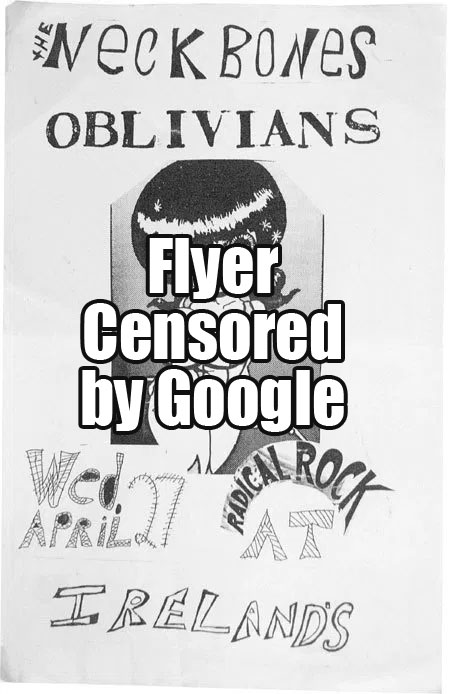

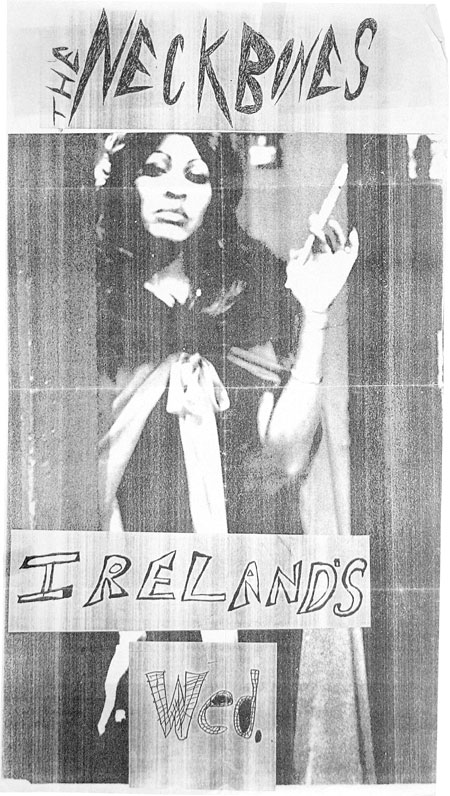

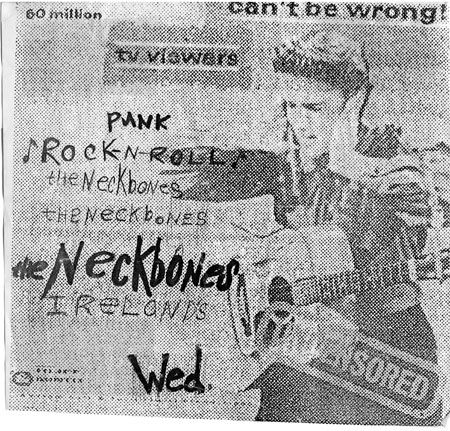

Publisher’s note: On July 20, 2017, The Local Voice was notified by Google Adsense that this page was in violation of their policies concerning “sexually suggestive or intended to sexually arouse. This includes, but is not limited to: pornographic images, videos, or games and sexually gratifying text, images, audio, or video.” We were told to either remove the content they would no longer serve ads to TheLocalVoice.net. Because it is not possible at this time to just remove their ads from just this one page on our site, we have been forced to censor the content of some of The Neckbones record covers, flyers, and videos. We adamantly disagree with Google’s assertion that we were serving pornographic images, but we have no recourse of action to challenge them. We apologize for having to remove The Neckbones original art.

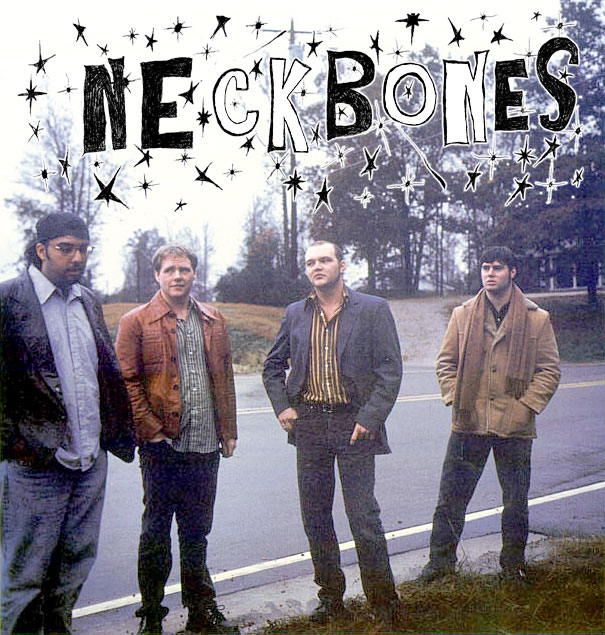

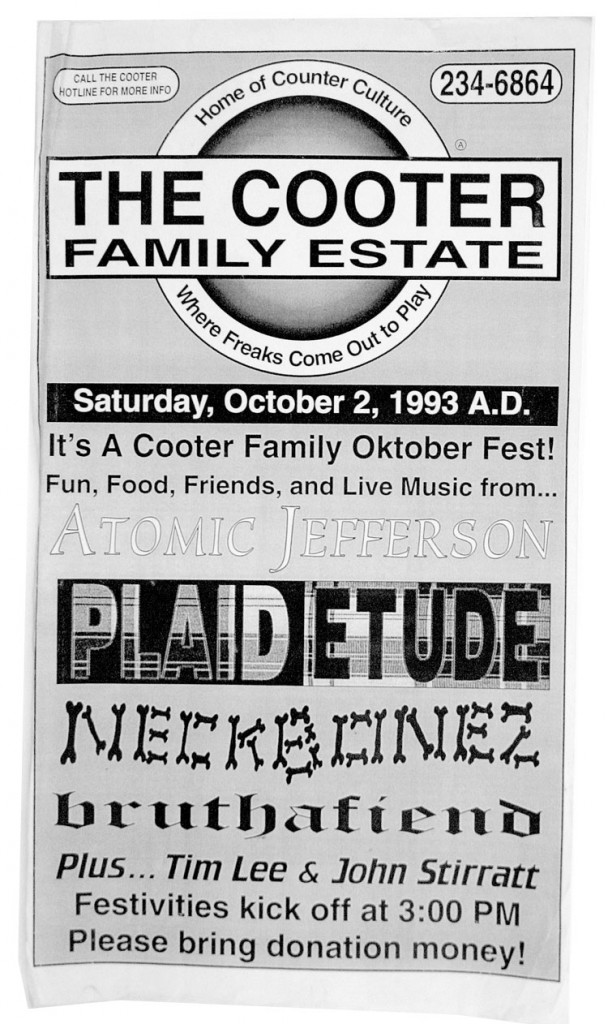

Oxford, Miss. (TLV) – The first time I ever saw The Neckbones, was in early 1993 at Lafayette’s (now The Library) opening up for Blue Mountain. The band consisted of Dave Boyer (guitar), Forrest Hewes (drums), and Robbie Alexander (bass).*

They looked like your typical Ole Miss students at the time, but these guys were rocking out to a high energy beat. Dave was plucking his guitar with his teeth and he held it behind his head to do a solo. It was awesome, but that was just the tip of the iceberg to what was about to happen to the band.

When Tyler Keith joined The Neckbones later that summer on guitar, the band went from being a good entertaining band, to a great rocknroll experience. If you were there, you know what I am talking about.

White Stripes, The Hives, The Oblivians, name whatever garage band you want. I have seen and heard a lot of these bands over the years. I’m here to tell you that The Neckbones blow them all away. They aren’t just one of Oxford’s greatest bands, The Neckbones are one of the greatest bands anywhere. It’s a crying shame that they never achieved the success they rightfully deserved.

In June of 2007, I interviewed Tyler Keith for The Local Voice.

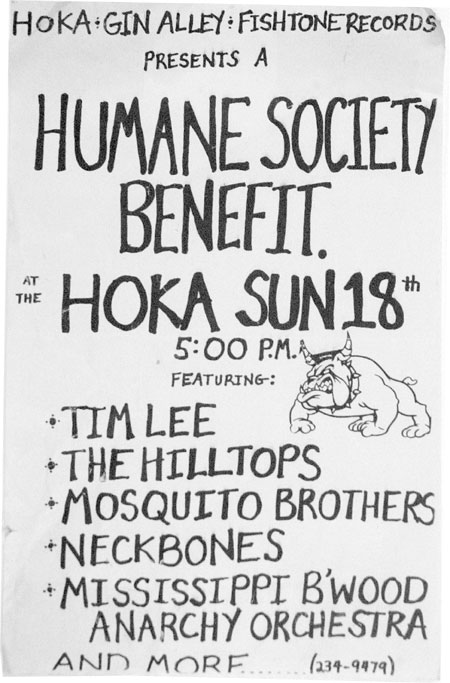

* On second thought, the first time I saw The Neckbones was actually in 1992 at the Hoka Theatre at a Humane Society Benefit show that also featured Tim Lee, John Stirratt, The Backwoods Mississippi Anarchy Orchestra, and the M0squito Brothers.

The Neckbones live at The Cooter Estate, 1993. Photographs and Collage by Newt Rayburn.

I’m personally excited about the Neckbones getting back together and I know a lot of other people are too, so let’s talk about The Neckbones. When did The Neckbones start, when did it end, and tell me who’s in the band?

The Neckbones started in 1992 or ‘93 before I joined. It was Dave Boyer, Forrest Hewes, and Robbie Alexander. They were a 3-piece and I joined in 1993. I started to live with Forrest, he had an attic space, I lived up there and we started playing. Dave and Robbie were gone for the summer.

It was right across from the Ice House on Van Buren Avenue. That was the old Hilltops house. Five people lived there at the time.

Yeah, so seven or eight years later, we stopped playing because our bass player quit, Robbie, and he quit somewhere around 1999 maybe and then we did another tour in Spring 2000.

We went to Europe with T-Model Ford and with Amos Harvey on bass. Then we just kinda didn’t play. It wasn’t like a breakup. We’ve gotten together for the 4 or 5 shows since 2000.

Tell me about The Neckbones records, the discography.

I think the first thing that came out was recorded by the Neckbones as 3-piece. They out a cassette called Painting in Trash. It was a really good tape but I wasn’t on that. A guy who lived in Oxford back then, Mark Roberts put out about 50 of them on his label, Fishtone Records. It was supposed to be more, but even the smallest record labels rarely come through with whatever their agreement was, even the cassette market. Mark ended up using most of the cassettes to record Clay Jones and Neilson Hubbard’s band, Spoon. That cassette was before I was in the band. I joined after that.

We did a 7 inch EP and that was released on the Seven Inch Mentality label in Memphis. That’s the one with the doll on it. That was our first 7 inch and a lot of those songs appeared on our first full length album, Pay The Rent, which we put out ourself. We recorded some of that in Memphis and some of that with Bruce Watson, I think, at Zombie Birdhouse studio, which was at the time out on Highway 6.

That old house that looks like a barn.

Yeah, so they must have formed in 1992 or maybe 1991 and then I guess about two or three years later we recorded a bunch of stuff, and Fat Possum wanted to release our records because we were having some big shows and stuff and playing really well. They had a conflict at the time with their partner company, Capricorn Records. We had the material for Souls On Fire but it took a few years for it to come out. I don’t think it came out until 1997, after Fat Possum switched to Epitaph Records, in between that time we did put out a single of “Hit Me” and “Bad Boy” that was on Sympathy For the Record Industry.

So why did it take so long, were you on Fat Possum for a while before a record came out?

We were on because they weren’t putting out any records for a while because of legal issues. Then that came out and then after that we put out another single “64 Days” and “We’re All Winners” on Misprint Records. That one came out right before The Lights Are Getting Dim, our last full length with Fat Possum. That came out in 1999. Then we have the 10 inch Gentlemen which was a lot of the tracks that didn’t make it on the record for whatever reason. This was our final release, which was one of the better ones. I like it a lot.

I have to agree with that. Tell me about the pre-Neckbones days.

I started playing music just as a kid, my family, my Dad, everybody played. I was forced into piano lessons of course. I played in the orchestra. My dad had a Bluegrass band, he taught me to play guitar and stand-up bass, then I developed from there. Yeah, I came from a music family. It was kind of square, I thought at the time. I discovered The Who when I was 13, got an electric guitar. In the beginning it took a while to grasp, to get confidence.

I played in punk rock bands, but just in bedrooms, we never played any shows. I couldn’t play fast. I was playing with the kind of people that wanted to play fast, I couldn’t. I was just inspired by that.

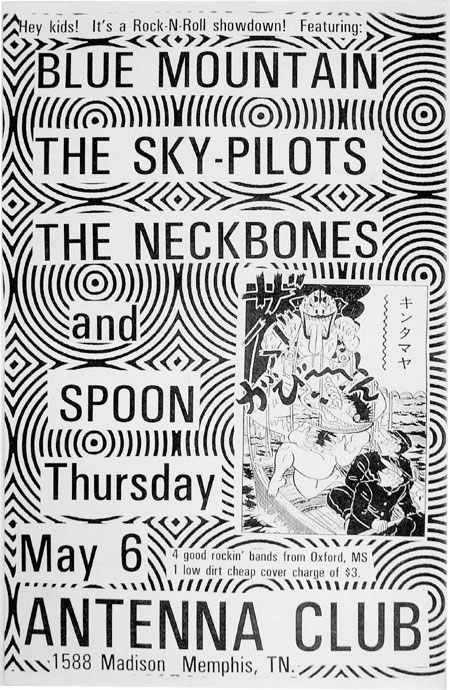

I moved to Oxford and started playing with Paul Tucker in The Sky Pilots. That was Spring 1991. That was the first real band I was in that played shows. He turned me on to a lot of great music. Paul had a bit more experience and stuff. He was a couple of years older than me. We played for a couple of years, two and a half years, maybe.

I felt like I’d gotten some rock lessons. Then I joined The Cooters as a drummer, but I wasn’t much of a drummer. But I was the original Cooters drummer!

How did you meet up with The Neckbones? They were playing around town at the same time as a three piece.

Well, I really liked what they were doing, they had a lot of energy and skills, to me they seemed different than the average band. When you’re young 20, 21, 22, whatever, 23, you live in crappy places. A $120 bucks a month gets whatever. I’d known Forrest from seeing him in the bars around town, and he had a place to live and I moved in his attic. He had a practice room set up for The Neckbones upstairs. Robbie and Dave went out of town for that summer that I was living there and we started practicing and playing some stuff.

I was starting to write songs and me and Forrest got a band together called The Recession Hookers with Gentry Webb… Raw Cooter… and this other guy named Lester. We went and recorded 4 songs. That was the first time I’d ever recorded a song that I’d written lyrics to, it was called “Deadbeat.” Yeah, that was before I was in The Neckbones. I think they had been talking about having another guitar player and maybe somebody else to sing because Forrest was pulling all the vocals.

A lot of those shows back then you know you would play two sets, two long sets a night, 25 songs, I think they wanted another guitar player and singer. I really wanted to play guitar so it worked out perfectly. We got that place out on Highway 334 at the corner of Fudgetown Road. We’d practice a lot. I immediately felt a real musical connection.

I think that was the first show I ever played with The Neckbones was at The Cooter Estate on Highway 334. We also started doing some shows in Memphis right off and they were going pretty well, playing with some bands like The Simple Ones. We played with them a lot down here and up there. Jared, the singer of The Simple Ones, had a recording studio in his basement. He was starting a record label called 7 Inch Mentality and he wanted to do a record with us. We went in there, some of the guitars plugged straight into the board. It was real raunchy, great sound. Completely raw.

The Neckbones already had quite a few originals before I joined. I just started writing. We had a great practice space out in the country where you could play all hours of the night. We recorded some more songs with Bruce Watson. I was not going to class at Ole Miss. I just played guitar all day! We had quite a bit of songs recorded. It took us a while to find somebody to give us the money to make a CD. I think at about that time they were really expensive compared to today. They’ve gotten cheaper since.

So we didn’t have two or three grand so we conned one of Forrest’s, Dave, and Robbie’s friends from the coast into putting out our first CD. I think he ended up going into rehab right after, so we’d kinda got possession of them! We didn’t really know anything about distribution or how to get them to anybody. Somebody probably still has quite a few of them sitting in a box somewhere, I’m sure. I don’t know who, but, so, yeah that was the first few records there. It’s a good album. Its a lot different from some of the other bands at the time.

Oh yeah! Some of my favorite songs that ya’ll ever did were on the first record.

It has a live quality, I think, because we were really having a great time playing together. It was like an electricity. There still is! A combination of certain people makes you play better. There’s a lot of competition and so forth, it makes things better inside the band. You have to keep up with the people in your band.

Well, y’all were really unique because you didn’t have just 1 or 2 songwriters, you had 3 in the band, at least 3, and then you had 3 different people singing songs, so none of your songs sounded the same, but they all had that feel.

Right, it was really, it’s hard to top that. If you were playing in a band where one person mainly sings, it’s a lot harder you know? It’s not as much fun really, to be honest. You rarely see 3 people singing. It sounds powerful. Our 7 inch was recorded in Memphis and our first CD was recorded at Bruce Watson’s house on Beanland Avenue. We looked up to Blue Mountain as a model, because they did a lot of stuff themselves, they worked extremely hard you know? I’d go over to their house and they were always playing music all the time, they always had a gig, Laurie always worked the phone. Blue Mountain, they were really a model of as far as working music, they didn’t drink which helped immensely, I’m sure.

Blue Mountain used one of Lawrence Wells’s paintings on their first record. He was an artist living in Oxford back then. I liked his paintings. He let us go through his paintings and we picked out this one that had like four insects on there. Lawrence was one of the greatest dancers I’ve ever seen at live shows, and just an all around talented artist.

We got Pay The Rent mastered by this guy from Memphis who had mastered amazingly classic records, wow, we’re getting him to do it. After we got all the CDs pressed up and played it for the first time, about the 4th song, it starts up and stops about 10 seconds through and starts over, which was, at the time, really heartbreaking. It’s no big deal now looking back, cause this was our first CD that was good and we were sure that something was going to happen like that. We thought that it would ruin everything, but it is great looking back.

Not long after Pay the Rent came out, you guys signed to Fat Possum Records. How did you hook up with them and what was it like being on a blues label, positive or negative?

Well, that’s a complicated question. I think we got on the label because they wanted to get a rock band on there. We were playing some shows at the time at Ireland’s, which is now Murff’s (editor’s note: as of 2014, this bar is now Frank & Marlee’s), and we were on fire and there was 100 people there every time, so crammed in there the floors would be shaking. We had some really rabid fans in town!

I’d known Matthew Johnson, who runs Fat Possum. I had a class with him on campus at Ole Miss. He saw us play, and I think part of it was, he didn’t want someone else to sign us before he did. I’m not saying anybody else would have, but he could tell we had something going here. It was an incredibly exciting idea because Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside are complete heroes. We’d been out to their club a lot, and it was some of the greatest music I’d ever seen… most unique experience I’d ever had.

The thought of getting to play with these people was a dream come true, but by the time our first Fat Possum record, Souls on Fire, came out there had been so much time gone by. And there were a lot of weird mind games going on where certain people were pitted against each other. It was really a stupid thing.

By the time Souls on Fire actually came out there was already certain resentments by certain band members and certain label people just because it’s a small town and I don’t think anybody in our band is particularly comfortable with authority. A lot of misunderstandings by what some people thought we should do. It was just complicated. There was a lot of push and pull, and there was an incident the day our record came out.

Well, lets talk about that. The night Souls on Fire was released, you guys had a party at Proud Larry’s and that night’s infamously known as one of the “Most Shocking Moments in Oxford Music History.” What happened?

It was a stupid drunken incident basically. There were some things behind it. It was a real triumph for us finally to have this record coming out. Some people… Matthew likes to push people’s buttons, that night he pushed the wrong person’s buttons at an inappropriate time, and was bitch slapped for it.

We payed for it in a lot of ways, but it was worth it. They were putting in their catalogs “The Neckbones are pussies but we love them anyway,” “The Neckbones sound like .38 Special.”

None of those tours with R.L. or Junior or any of those people came out of it. Sort of backbiting behind each other’s backs, but we were guilty of it. But you know, artists don’t really want to have an authority figure with the people you’re supposed to be working with, a clash, basically where you don’t have to tell me what to do.

It was kind of stupid, macho crap. The incident did happen, the only reason it was a big deal was because some people around town might have enjoyed the story.

It was definitely talked about, it was the night your first record with Fat Possum came out, it was a huge talked about incident at the time. Do you think that it really hurt your career with Fat Possum? It seems that they didn’t ever really push you guys like they were pushing other artists on the label, in my opinion.

Yeah, it did hurt us but then it happened again a couple of times because I think that what we felt whether it was right or not, we felt a lack of respect. So yeah, i think it hurt, it’s one of those things that I wouldn’t take any of it back, cause I’m not going to back down from any of that. I think it hurt everybody involved. It hurt, we could have sold more records… it could have been more enjoyable, but I don’t regret it, but yeah, it did hurt. It was dumb… rock’n roll is dumb, that’s just the nature of it.

Let’s talk about Souls on Fire. A lot of people consider that the quintessential Neckbones album, tell me about recording that.

We recorded this one at Bruce’s studio. We did record 1 or 2 songs with Jeffrey Reed at the Hog’s Nest in Little Rock owned by Dale Hawkins, writer of “Suzy Q.” He’ as legendary rockabilly star. We recorded some stuff with Jeffrey Reed over there and that was really good. But mainly I think this was recorded in that warehouse on South 16th. It took a long time to make this record because of various business things. We had a lot of songs to choose from, a lot more time, we’d play quite a few shows, it was more of a mature effort. I think it is probably all the way through our best record, but not by a lot. I think the other ones are really good, close to, I think it’s just because we were at the top of our playing.

Tell me about the cover of Souls on Fire, who is this girl?!

That’s Emily Marshall, a girlfriend of Dale Beavers. She sent him this picture for Valentine’s Day. She actually sent him a whole roll of these pictures for her Valentine’s Day. Dale was a friend of mine. I just picked this one out to use for the cover. It seemed to capture something. I’m not sure what the heck is going on there! We ended up having to pay her for it.

How did she feel about it after it came out?

I think after she got paid for it she felt alright about it, I think she might have liked to have had a choice in which photo we picked.

Let’s move on to The Lights Are Getting Dim. This record was recorded by Bruce Watson again, but John Stirratt of Wilco mixed this album?

Yeah, he did, he mixed it after we recorded it, we got him to mix it. He was from Oxford, and we kind of felt we needed a fresh set of ears on it. We knew he wouldn’t really charge much or anything. He has a really good ear, really wanted to get somebody that knew us and knew what we did, some fresh ears on it. That album was recorded at Bruce’s house off Highway 6 going towards Pontotoc. There used to be a karate dojo in back and we recorded in there. It was really fun sessions, we had a lot of people play on it!

Yeah, tell me about that, you got JoJo from Widespread Panic, Jack from The Oblivians, pedal steelist Bob Egan, Cary Hudson and Laurie Stirratt of Blue Mountain. That’s a room full of people right there!

They all came out at different times. Bob Egan was living in Oxford and we wanted him to come to the studio. JoJo lived here at the time and was a partner in Fat Possum and he’d always liked our band. Jack Oblivian was a friend and we were definitely very big fans of his music. I think we were just trying to do a little more with more instrumentation. There was a lot of, gotten to the point where a lot of bands were just sounding just the same old garagey sort of sound. I think we were trying to, trying to… I don’t know if it worked or not… trying to have a little bit more layers, a few… the saxophone, piano, to make it a little more nuanced.

That’s pretty natural for any band writing their 3rd album definitely. You think about what else can you do in the studio besides just playing straight up rocknroll, sometimes its fun to experiment and you guys do that on this album.

Yeah the whole part about being in a rocknroll band is pretending like you’re whatever you read about your hero or whatever, hey, I can go into the studio do something interesting! That’s part of the fantasy, that’s part of the fun. I think it turned out really well.

Another thing about this record, The Lights Are Getting Dim. This record barely came out because another incident occurred. I basically had to beg them. Fat Possum was charging us for studio time, against our royalties. They said they would put it out but not do anything. I borrowed money from my sister to hire a publicist.

Amos Harvey was touring with and booking R.L. I think he got us on a couple of weeks there right when the record came out he ended up booking us in the spring in Europe clandestinely, without the label’s knowledge. I basically hired a publicist for 1500 bucks a month to help, but it started to die around that time. It was such a struggle to keep it going, all that business trying to afford to tour, just trying to live a slightly clean life.

We had a lot of left over songs so that’s why we put out Gentlemen, our 10-inch. We’d actually done a lot of sessions for The Lights Are Getting Dim and some is from Souls on Fire, a lot of stuff left over, both those records had 16 songs each. I don’t like a record that’s 70 minutes long, you should be 35-40 minutes, after that people get bored. Just because you can put 85 minutes on a CD doesn’t mean that you should. We had a lot of good tracks left over and I know a lot of people are like, “why didn’t that get on,” it’s just when you start looking at the sequencing, trying to put an album together, some things just don’t make it on there.

The 10 inch, Gentlemen. I don’t know how many people heard that record compared to Souls on Fire or The Lights Are Getting Dim, but it is really, in a way, your best release.

I think so, it’s a solid, it’s a really great thing.

The cover art, everything, the whole package is there.

I think it was. The weird thing about it was the songs got left off those other records, but when you put them together, they seemed like they fit just right.

I didn’t know that record had been released. I was with The Cooters in Nashville, and we were at a record store and I was like, “Hey, look at this, I’ve never seen this before” and turned it over and saw the back cover and everybody was on the floor laughing! That’s one of the greatest back covers ever!

I love vintage records, they look cool. Yeah, so that was the last thing that we put out and then Robbie kind of moved on, he was tired. What happened basically the end we had a show in Memphis and we’d been struggling for years, we have like a handful of people who really like us that came every time, really good people, wasn’t that many, and we were really starting to make a little headway up there, the shows were starting to get a lot of people there.

We had one show that was our own show. We had a lot of people. That was probably our biggest show ever, our own show, not opening up for anybody. Robbie just did not show up, and he just refused to come. George Sheldon was there so we were like “George, jump on bass, you’ll have to hang on!” So he jumped up there and it turned out to be a really great show.

But the thought of getting somebody else permanently to replace Robbie… I think we were all just kind of like, we’d done a lot of good things in our time, getting somebody else may not really be worth this. We didn’t have a label then either. Basically, we were back at the beginning, I don’t think anybody really wanted to try and do that kind of work, you just get tired of it, but we got together for a tour of Europe with T-Model Ford in Spring 2000. That was a really great experience. The Neckbones didn’t break up, we just decided not to play for a while, kind of take a break.

You did the European tour with T-Model Ford in 2000 with Amos Harvey on bass, tell me about that because that’s obviously not something that a lot of bands get to do.

Amos orchestrated that tour because he liked our band a lot, he could play bass, so he could play bass with us and take us around with T-Model Ford, I think he felt some empathy towards us because he booked this tour behind Fat Possum’s back, kind of stuck his neck out there doing it, which we really appreciate.

Fat Possum just wanted to write us off and forget about it but we didn’t get to do that because one of the best experiences ever was had to play all these shows with T-Model Ford who is very inspiring person. I think he has more love for music than any person I’ve ever seen. I’ve never seen anybody play as much.

He comes to the club at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, he starts playing at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, you have to take the guitar away from him that night, he’ll play a good 10 hours with a smile, he had an incredibly hard life, he’s not bitter at all, he’s tough. We were drinking and partying up in his room after shows and he’d have his shirt off and he pulled up his pants, he’s got this ball and chain scar on his ankle from being on a chain in 1948. This guy stabbed him in the back. He’s like, “Look at my back. I had to whip my knife out and grabbed him by the neck and killed him after he stabbed me.”

Just telling stories, it was funny, he got a lot more action with the women than any of us! He would totally show off. He would hook up with these odd European women and make out in front of us, he’d be like, “hey, watch this.” It was pretty amazing, an 80 year old man is getting more action than you, and you’re like 27, that’s pretty humbling, you know who’s got the goods.

You guys covered a T-Model Ford song, which album was that on?

The Lights Are Getting Dim, “Nobody Gets Me Down.” We used to play that every night, he liked to hear it, he’d get excited. It was really a great experience being around him. We did another 2 1/2 weeks with R. L. Burnside. That was as equally another really great experience. These people are very giving.

We were staying on R.L.’s floor, he’s like, “Get up in the bed with me.” He was just really genuine. That just made it all worth it for me, to have some interaction with those people, that made everything we went through worth it. We went to the East Coast and Mid-West with R.L. He was playing with Kenny Brown and Cedric Burnside, it was 3 piece, two guitars and drums. We traded jokes with R.L. and drank a lot of whiskey. So much of it is an alcoholic haze. We did drink quite a bit.

You guys would out-drink every band in town!

We did, you get a reputation for it, which was sometimes harmful. We rarely did bad shows despite how much we drank, there were a few, but not many, there was definitely a lot of drinking. One time in Europe, we played where marijuana was legal. We smoked so much of that, I couldn’t play, completely incapable of doing anything, just standing on stage going uh, uhh,uh, I can’t… I don’t know… a lot of the memories are not clear.

You didn’t know what to expect at a Neckbones show. There was a lot of chaos going on; you didn’t know if a fight was gonna break out, or somebody was gonna get smashed or what! There was a show you guys did on Halloween of 1995 at Ireland’s. You bought a Ventura guitar that day and I guess you couldn’t keep it in tune or something. The room was packed, but you got pissed off at that guitar, so much so that you started swinging it and you smashed it in the middle of a song! I couldn’t get out of the way fast enough, and you ended up breaking…

I broke your toe!

You broke my toe! I’ve still got what’s left of that guitar, too!

That’s awesome! I’m sorry about that!

It was a great memory. I got my toe broken by a Neckbone.

Robbie used to play with a broken arm for a while. He had a cast and he would smash his cast open every show, he’d have to go get another cast every time we played. I’ve never felt that kind of energy focused since. But I hurt myself pretty bad in the end, just jumping off stuff, my knees. I’m kind of frightened to do that stuff, I mean, maybe I’ve gotten too old.

Remember that show, in Memphis, I was talking about that George Sheldon played? I climbed up on a stack of speakers and it was way too high. But once you’re up there you can’t just climb back down, you have to jump; I made it, but the shock – it hurt. The music was real physical and I really enjoyed that. Because people would get, the crowd would get whipped up in this strange, chaotic circle. Someone could get punched or something could get broken, it was great.

So, towards the end of The Neckbones… I don’t know if “broken up” is the way to put it, but sometime around that time was when you started The Preacher’s Kids and did the Romeo Hood album. Was The Neckbones still going on during that time?

No, that was after we went to Europe and we really didn’t have a bass player and I was still kind of eager to go on the road. I think I was the only one at that point. I had some songs at that point, and it was, again, taking a long time for the record to come out. We weren’t the best practicing band, but I was doing a lot of home recordings and stuff.

So, I just went down and recorded a record of these songs I had with basically Blue Mountain backing me up down at Chris Hudson’s. And it was kinda just gonna be a solo record, and I just called it Tyler Keith and The Preacher’s Kids cause I didn’t have a band. So it wasn’t supposed to be anything like…I just wanted to make a record, really…

But that ended up being your next band.

Yeah, cause Dave basically started The Cool Jerks right around then, but Dave was playing in The Preacher’s Kids at first, too. So, it wasn’t really that serious at first. Black Dog, the label wanted to put out the record, so it got a little more serious, I wanted to go out and put a band together or something. But at the time it was just to make a record, really. I had a collection of songs. Sometimes you just write songs in clumps and it’s hard to go on to the next clump if you don’t do something with this, you know what I mean? So that’s kind of why, I just had some songs that I wanted to get out. Cause if you don’t, you lose interest and then you even forget about some songs. Somebody’s like, “You remember that song?” and you’re like “Oh yeah…” For me anyway, unless you put it together it can just go all over the place.

You said that after Robbie quit the band, you weren’t really wanting to replace Robbie, but I understand he’s not playing at these Neckbones reunion shows?

He’s not. But we played a couple of years ago and he played. We played like two years ago and he played on that, but we haven’t really been able to get in touch with him and I just have the feeling he probably doesn’t… I don’t know, he’s kind of a reclusive guy. I think he’s in Florida somewhere, but we decided to play anyway with Van Thompson. I haven’t seen Robbie since 2004.

Talk about some of the shows you guys played.

The Cooter Estate was really the first venue that I played. We played there quite a bit at first, and there was not really a place where touring bands could play, punk rock bands, at that time except The Cooter Estate. So, we started playing there and those shows were always great. It was best to be the first couple bands, so you could get in before the cops came or the keg floated or somebody broke into your car or something, but yeah, those were great.

Then the Hoka was always fun cause you could play films behind you and that was always fun. You could bring your own beer. We played with The Oblivions, Load, Man or Astro-Man, The Woggles, so many band… Like I said, a lot of brain cells are gone since then. But I saw Beat Happening, and some other stuff, Grisham’s Army – I don’t think we played with them, but I saw them.

Let’s see, Ireland’s… that was… Forrest had a lot of friends from the coast and there was a lot of wildness. So at the time there were a lot of Mexican pills. So some people were wild and some people could barely stand up. That’s when we got a full set of basically originals, a long hour and a half of music and it was jam-packed in there. When you played upstairs, the floor would just be bouncing.

That’s the weird thing about playing in a college town – after three or four years, half your crowd or more has graduated and moved on and you kind of gotta keep starting over. But that was our first big crowd; it’s really good for your confidence. There was always this feeling of you gotta be cool, but it was good to have your own thing, good to have that Ireland’s thing early on so you could be more self-reliant and be more secure.

Yeah. You guys definitely had a loyal following.

Yeah, but it was not really a scene, per se, here, because all the bands were of different genres, but that was always good, I thought. Because you totally develop independently of other things which is really important for trying to have some originality as an artist.

That time period 1993, 1994, was a very exciting time in Oxford.

It was. Everything was still cheap to live, too, and the drinks were cheap. I don’t think the money you pay to see a band has changed since the 1960’s, you know bands now get paid nothing. Back in the ‘60’s they were getting 2 or 3 bucks at the door. Now, forty years later, we’re still getting 5 bucks at the door. People will complain about a door charge, and then they’ll go in and buy one shot for like seven bucks and throw it down their throat. That’s just sad. I think that’s a problem, why bands can’t charge… people go in there and pay 3 dollars for a cup of draft beer and then no one will wanna pay you. That’s the whole problem, why bands can’t afford to keep doing it. Inflation’s gone up, and things are more expensive, but I don’t think the pay for bands has really changed much. I don’t know, maybe that’s just bitterness…

No, you’re exactly right.

And the promoters aren’t willing to do their job. The promoters, they book you, they don’t promote you. There’s no promotion involved. I’ve booked your show in here, that’s about it. Here’s your two drink tickets, have fun with that. I think it has something to do with Baby Boomers, the people that run these bars, the most tight people that have ever lived. I think it has something to do with Baby Boomers, the people that run these bars, the most tight people that have ever lived. I think the state we’re in in general is because of this.

Well, now that we’re on this subject, Oxford in ’93 – ’94 compared to now, I mean it’s a big difference. Talk about that a little bit.

It’s a big difference, community-wise…

Do you think The Neckbones could, if it had never happened, do you think the same thing could happen now in Oxford?

I think it’s possible, yeah. I think there’s some good younger bands in town here that are coming up. The worse it gets, the more of that is gonna come out, cause kids are the first people to hate the homogenizing of their own town. We’ve got a lot of good bands coming down the track here just because…there’s a lot of real stupid kids around, but there’s a lot of really sharp kids that are digging the stuff, maybe not as big a crowd of people.I think, yeah, the college kids have changed a lot. They all look exactly the same, but some of the other kids that aren’t like that…I don’t know. There’s less, but the kids that are into good things are more into than I was because they have more access.

1993 there was no internet. It’s easier for bands to make connections now. But they can also find out more about the roots of things. You can go on there and find out about the MC-5 really quick. I remember trying to find those records before they were out on CD. It would take years to even find one of their records.So, I think it could happen here and it probably will because you can’t really try to make something, make this town into something that its not.

This town is not a resort, whether you want to make it one or not. And if, God forbid, if there’s ever any kind of economic crisis in this country or stock market crash, these places are gonna be empty. I mean, these people have so much money that they’re allowed to buy these extra houses, but eventually, if something happens, I don’t know. That’s getting off on a tangent. This is a nice town, and there’s a college here and there’s football and baseball and stuff, but it’s not a resort town. There’s nothing to do here except drink.

I have to say you’re one of the lucky musicians who has an apartment that’s almost on The Square. I know a lot of other people that can’t even afford to live near Oxford. Do you see that kind of stuff hurting the music scene here? Is it running people off?

Yeah, it does run people off. You get the impression that there’s some people in the town that would like to see some of the riff-raff gone. I think it’s just natural anyway when people realize, I can’t live like a college kid anymore and then they move. That’s a natural progression and it happens. And I regret not leaving here a lot. I had opportunities and I didn’t. Sometimes I regret it, but I don’t know.

I’m personally glad you didn’t because Oxford’s been a lot better because you’ve lived here.

Well, I regret it and don’t regret it. You sacrifice a lot of personal relationships by trying to stick around and keep a band together and be a musician. The other thing about this town is there’s not industry here. You can’t go get a job anywhere except at the University or at a restaurant, or the hospital. You get a certain age, I don’t wanna live like a scumbag and live, work in a restaurant anymore. I guess I just hung on longer than most people, I just have a high tolerance for it. I don’t know. I like this place, but I think about leaving almost every day. But I do like it here.

Where do you see yourself in 10 or 20 years? Do you think you’ll still be here?

I don’t know. There’s a good chance I’ll still be here, or be back here from somewhere. I guess I keep saying about Oxford, it’s not an amusement park, but it’s not the real world necessarily either. I hope to be just playing some music, hopefully have 6 or 8 or 10 more records out and hopefully will have made some money on them somehow.

Do you think The Neckbones could ever record again?

Yeah, I’m sure we will. Cause Dave’s got a really nice studio in his basement, so we kind of have some tentative plans to do that. We’re talking about playing in Nashville, cause they live up there, but we haven’t booked anything at the moment.

So this may not be like a one time thing, it could be a semi-regular…

I hope not, I mean maybe biannually and then maybe a few more if we put out a record or something. I’m keeping The Preacher’s Kids going and I’m playing some solo stuff, Kid Twist, yeah.

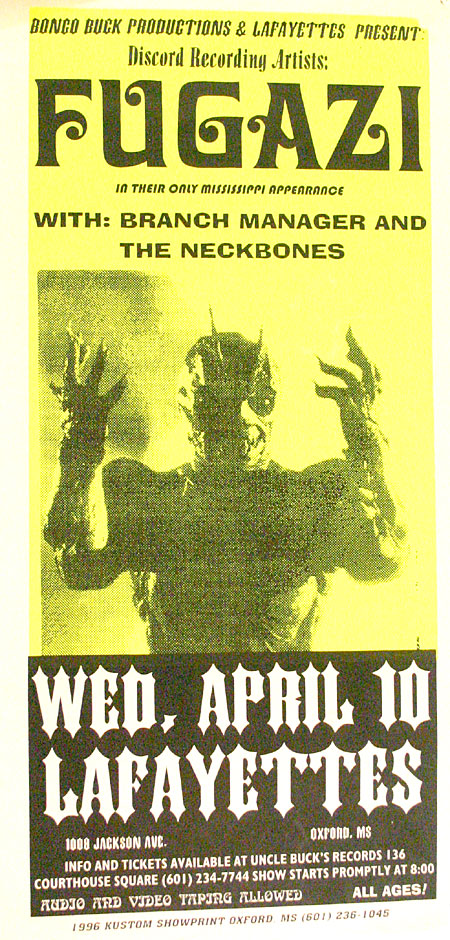

OK, back to some Neckbones stuff… You guys did a show back in the day with Fugazi at Lafayette’s, and that show ended up being part of Fugazi’s movie, Instrument, and there’s a section in that movie where they’re backstage at Lafayette’s and you can hear you guys playing in the movie. Tell me a little bit about that experience of playing with such a big band.

Well, I didn’t really know that they were filming that. I guess I maybe remember there being some cameras or something, but we liked Fugazi a lot and it was good to play an all ages show with a lot of people. They were fairly friendly. I think I saw a couple of them drinking a beer or two, and that was kind of a shock, you know…

A scandal!

That was great, yeah, and I remember watching that movie and going, Hey wait! They’re playing “Souls On Fire”… you can hear it in the background playing! So, we’re pretty much on our way now. We had another song on some Christina Ricci movie. It was “Scronky Tonk”, but I can’t remember the name of the movie.

Let’s talk about some of The Neckbones songs. What was the typical writing process like? You joined a band that was already together and they already had a style.

It was usually just kind of like bringing a song in, and bringing music in, and Forrest would just write some lyrics, and then Robbie was always good about putting in some bridges, but mainly it was just like bringing in your song. We initially practiced a lot more, so there was more interaction.

Towards the end, we rarely, if ever practiced, so it was extremely hard to collaborate. Usually we would practice the day or so before a recording session. So a lot of the stuff that came off hadn’t really been played much, which was good and bad, in some ways it was more spontaneous ideas, but in other ways, there could’ve been some better parts that we came up with that we did end up coming up with later live, on them. And sometimes I wish we would’ve played this on the recording.

It got to be kind of an issue for me, the lack of practice, and I was just as guilty as anybody else of not getting it together, but it became a real problem towards the end was not practicing. Everybody just had to work, and had weird schedules at different times, and basically none of us, including me, made the effort to make a specific time every week, Sunday afternoon or whatever. Seriously, we didn’t practice for a couple years, and the same with The Preacher’s Kids, we haven’t practiced with The Preacher’s Kids… and it’s bad when that happens.

Do you think that’s why you’ve been doing more solo shows?

That’s part of it. But part of it is that I never had the confidence to do it, but now you don’t have to practice with a band to do a song. You can write it one afternoon and then that play it that night live, if you want.

The Neckbones were notorious for never including any lyrics in anything that you ever released, why was that?

I don’t know, I guess we probably weren’t that confident in it. Maybe it was just, I don’t know I guess we didn’t really think about it in that way.

Well, I’m gonna mention a song, and I want you to talk about it. “Teenage Rock Idol?”

Okay, that was just a fun track. I guess at the time there was a lot of… I guess it’s kind of a fun mock of a straight-edge band or something. At the time I had serious issues with music that was preachy, cause there was some of that around. And basically it was just the riff, and then I just put something to it. I thought it sounded good; it was kind of comical. It was sort of about this indie-rock elitism that bothered me, just this pretension that I’ve always despised in music of any type.

“Crack Whore Blues?”

“Crack Whore Blues” is basically an empathetic song towards a crack whore. I wrote that the night before the night we had a recording session. I decided I was gonna write the most simple song I could do, and I had the lyrical ideas. It’s about realizing that a crack whore is… you’re only really a few steps away from that, or I feel like I am sometimes… Anybody can end up that way. Sure, and the beginning of that is the same as a john that goes to a crack whore, you just wanna get some kicks or whatever, but then there’s certain rules, like, dealing with whores… (laughs)… you just know this is about the money, has nothing else to do with it, you just gotta watch the transaction… I don’t know. That’s enough about that…

You wrote that the night before you recorded it?

Yeah, and I’ve kind of gotten to a place where I’ve done that quite a bit where it’s just like, you can over think things too much. And just say, I’m gonna write a simple riff, the simplest thing, and just put it together and not think about it and not over-analyze it and just see what happens. And a lot of times it works, your first instincts are the best.

That song, I remember seeing Matthew Smith cover that on acoustic guitar…

Yeah he did a great version of it.

Yeah, it was kinda cool. What’s that like, seeing someone else playing your song?

Excellent. It’s the best feeling. Because I didn’t know him when he moved to town he was doing it, and somebody told me and I went in there, and it was awesome. Yeah, it’s great.

What was The Neckbones’ approach to songwriting, keep it simple?

Well, I think that each song was different. There was an effort, maybe not talked about, to have a wide range of types, or whatever just came out. It was naturally loose, no matter what, which is always good. But it was tight; it was this weird dichotomy of tight and loose that the best rock and roll bands have, I think. And we just had that natural, we would never be rushed, there was no way to be that tight for us, because, me personally, in the beginning I was just not that good of a musician, so there was always gonna be that rough element. Dave was always great; he could always play. It wasn’t really a conscious effort of that. But there was a lot… the studio involved a lot of drinking and partying and it was always really fun. We’d have go record, and then get up and go to work the next morning and still be drunk.

Was that ever an issue in the studio, drinking too much, or you just did it and didn’t worry about it?

There were some issues. Some people got, like, peed on and stuff just from being too drunk. Luckily the tapes never got peed on. It wasn’t ever an issue in the studio. It was an issue sometimes live, but not that often.

“Cardiac Suture?”

Yeah that was kind of, I don’t know, I was trying to step it up a little bit as far a step away from “Crack Whore,” more of… I hesitate to say serious, but more of like a real, emotional, I don’t know, a creative type of thing. I’d found the title in this place, and I guess it was more of an attempt at crafting something a little bit more interesting than before, a little bit more depth. It’s just about a person, it’s the image of a surgeon who has a certain ability. At the time I was dating someone. Have you ever met someone who basically just saved your ass, saved your life. You know what I mean, it sounds over dramatic, but it’s just about somebody you meet that knocks you out.

“Sick Twist?”

“Sick Twist” was kind of like a “Crack Whore Blues,” quick type. It think I was conscious of having songs that – I personally like music that people dance to, and I wanted to make a song that people could easily dance to and I think the lyrics are meaningless and it’s just a fun, dance type number. I’d rather have girls dancing at the front than a bunch of shirtless dudes punching each other. That’s me, call me crazy. I like the riff for it, but the lyrics are totally stupid. But yeah, it was conscious to make a dance song.

Well, since you’re an expert at it, what makes a good dance song that girls really get into?

Well, if it’s too fast, a girl can’t dance to it, and if it’s too slow, they can’t. If it has too many stops it throws people off. You have to have a good beat, it has to have a hook and it’s a classic formula.

“Vice Lord?”

“Vice Lord.” That was my attempt at writing a rap song, but not rapping, just trying to, I don’t know what you call that… the Vice Lords… just this pretending to be… I don’t care for rap, but it was almost like, at the time I was not exactly living a clean life. There was lot of drinking and partying and stuff, so I just felt like this, I don’t know. I just always liked it… when I lived in Jackson in the 1980’s the Vice Lords were big and I always thought that was the greatest name. At the time I kind of felt like a Vice Lord, cause I was living in an extreme manner. It’s kind of like the blues songs, like “Who Do You Love,” you know, cobra snake for a necktie, just bragging.

“Red Wagon,” which I have heard you do solo.

Well, I just had a song, Forrest wrote a verse of it and I thought he would sing it really well and… Bob Egan put the pedal steel on it and I think it sounds great. I grew up with a lot of country music. We were trying to do some more textured stuff, that maybe a lot of other bands weren’t capable of doing at the time.

“Eyeful?”

That was one of the first songs I wrote with The Neckbones. It was just about looking at people and being disgusted by the things that they enjoy. If you really look at something, just by noticing…I don’t know, I can’t really analyze it too much, it basically was one of the first ones I did with them, it was real fun to play.

“Pursy Lips?”

I had heard that phrase from something, I think some kind of Jack Kerouac poem or something. I thought it would make a funny…you could say that and people would misinterpret you, and you could say, “No, I didn’t say anything bad.” And I just wanted to do like a stripper type song, and just do it in the studio, and just, hey let’s try this. Basically just made it up on the spot. We got Jeff Calloway on trombone there, just trying to be spontaneous. It was stupid, sleazy.

“Art School Dropout?”

Yeah, that’s about when I quit school I wrote that song.

It was about quitting Ole Miss?

I was basically an English major, but it’s the same thing, I guess. We started playing a lot and I would just rather have done that. I was just in no rush to get an English degree and go out in the world and teach High School or something like that.

So I understand you’re finally going back to Ole Miss to finish your degree?

It feels like I lost, you know. I feel like I failed in a way.

Well you shouldn’t feel that way, cause you…

Well, all I ever wanted was to be able to do was be a musician just for a few years without having to work another job. And I never succeeded in that; I always had to work. Just a couple of years to be a musician, but I didn’t do the work it takes to make that happen. It was always something. If you have something to fall back on, you know, if all else fails I’ll do that.

So I guess all else failed and so I’m back to it, so part of me is completely, just, I feel like I lost in a way. But another part of me just looks at it, like, I don’t have much and it’s just an accomplishment. Plus my dad said he’d buy me a guitar if I graduated from college. I don’t know if he remembers it, but… Yeah it would make my parents really happy. I have like 12 hours, I have 2 French courses which is gonna be hard. 200-level French courses.

Well, I can understand how you feel that way, but I don’t think you should because you have all these great Neckbones albums and all these great Preacher’s Kids albums…

And I’m proud of that. I know. I’m lucky in a lot of ways. I think we did get a streak of luck with Fat Possum in that we got something right off which gave us a lot of exposure despite whatever problems arose from it. A lot of people would’ve killed for just that but we did put in a lot of work.

“Dead End Kids?”

“Dead End Kids” was sort of about myself and a bunch of other people at a certain time at Ireland’s, right at the peak of that Ireland’s thing. There was an instance where some kids set fire to their frat house or something and split town and I just thought that was great, cause I was feeling like that.

Well, what is your favorite Neckbones song?

I don’t know. I don’t really have a specific favorite. I like playing “Superstar Chevrolet” – is really fun to play. I like “Ocean of Blues,” really fun to play. I like playing “Cardiac Suture” a lot. I really enjoy playing the stupid covers we play, like “Crackpipe” and “Bad Boy” and stuff. I really enjoy playing a whole set because it goes in a lot of different directions. So much can happen, and it’s really hard to say one thing, but just doing these practices has been great, it’s just awesome. It just goes so many different places.

Well, that brings up something else. Obviously you’ve done a lot with The Preacher’s Kids, too, both bands have been really great. You’ve got awesome albums with both bands, but what’s the difference between playing with The Preacher’s Kids versus playing with The Neckbones?

The difference is that so much of The Neckbones for me is, that it’s like my DNA, because so much of my development, so much that I learned just form the act of playing, its something that’s ingrained. There’s a certain dynamic and energy that comes from The Neckbones because we came together at such a critical time in each of our developments and we became really close. There’s that kind of unconscious connection.

And then the Preacher’s Kids, frankly, some of the songwriting I think I’m doing better and it’s easier to focus on that part. We’ve had a lot of band members, that’s one different thing. Playing with Jon and Frank and Van for the last two or three years has got a different kind of dynamic. It’s still powerful, but it’s more interesting because it’s more insular. It’s more going inside, it’s more like imploding.

Then like The Neckbones is like going out. And the older you get as a musician, the more you can do that. It’s a more intense feeling than the other thing. Even though that’s great — going out — but the more intense artistic feeling is The Preacher’s Kid’s with going more inside yourself than bringing inside out. That’s the difference, I think. It’s just two different things.

When you’re younger, that’s more important for you, but then when you get older… see with The Neckbones, sometimes I just like to jump around and explode. Sometimes with The Preacher’s Kids I’ll make a point to see how still I can be and just deliver and project and get into the emotion of it more instead. I think that’s the difference.

It’ll be interesting to see what the new Neckbones songs are like, cause you guys are a lot older and a lot wiser and more experienced.

It’ll definitely be different. There might not be as much goofy, “Sick Twist” type stuff, for better or for worse. Probably for worse, but I don’t know.

I’m sure it’s gonna be great. I’m excited you guys are playing again. Alright I got just a few more questions. Are there any Neckbones albums that are still available?

Yeah, you can still get Souls on Fire for sure from Fat Possum. I know they printed up like 10,000 copies cause what Epitath was doing at the time, so yeah, there’s plenty of those. I imagine there’s plenty of Lights Are Getting Dim available on order from Fat Possum. As far as the rest, the singles are probably fairly rare. The LP’s might be rare, but the 10” is still available through the record company, through Misprint Records. But probably a lot of these records are not in stores. Pay the Rent isn’t available.

Do you think you’ll ever put it out again, cause it’s an awesome record.

I’d like to put them out and put the 10” on a CD or something.

Do you guys have the rights to your albums? How does that work?

We do to Pay the Rent, and Dim. I think we had some leftover stuff, some B-sides and stuff that we might put out on some things, too. I know that there’s some things from before I joined, too, that will probably come out sometime.

Well, just going back to the Fat Possum thing, you talked about all that happened and all the chaos that surrounded back in the day, but what is it like now? Is that all water under the bridge, or is it all smoothed out or is there still some of that…

You know, I don’t worry about that stuff anymore. Whenever I see those guys it’s just water under the bridge for me. I’m not saying that I’m completely fine with everything, but I just have a lot of other stuff to worry about. For such a long time it seriously bothered me when I was in the band. It sort of went…when we stopped I was able to not let it bring me down, I just let it go. Cause then you have other labels and you have a new set of resentments with new people you’re working with.

All these labels, and the small ones are the same as any big ones. My advice to anyone out there is put out your own records. Especially now with the internet and all that, you don’t need anyone to do anything for you. And you’ll own it, and you’ll be happy with it and you’ll have no one to blame but yourself and it’s just better to do that. Unless you get a large amount of money up front from a label, you should never…a small label just gets you for less money. It’s complicated to make something and then do a lot of touring and then owe people money.

Is that what’s going on with Fat Possum now?

No, we don’t owe them money, but just after a while it’s just useless, it’s kind of pointless. You just gotta let it go until you get some kind of opportunity to do something about it which would be just try get your records back, buy them or something.

So Fat Possum still has all the rights to those two records, then?

Yeah. But it was a group effort in fucking it up, on both sides. It’s hard to look back and say…right now I just really don’t care. But there are some funny stories, especially once you start drinking and stuff it just gets funnier.

Well, should I go get us a six pack or what?

Well, they just get embellished a little more, is what I’m saying. Have you ever seen that movie The Longest Yard, with Burt Reynolds where he asks that old timer who got like 20 extra years for punching a guard, and he asks him if it was worth it? And he’s like, “It was worth every day I served,” you know that’s kinda the way I feel. Whatever we did, whatever Dave did, just whatever.

copyright © 2007, 2014 The Local Voice – Rayburn Publishing