This photograph is thought to show the devestation of Oxford, Mississippi after August 22, 1864. It was verified in the 1930s by a local DAR chapter. However its authenticity is disputed.

On August 22, 1864, Oxford, Mississippi was deliberately burned by the Union Army during the Civil War.

Just like the Civil War itself, the reasons for this tragedy are complicated.

by Newt Rayburn

United States President Abraham Lincoln was deeply invested into three years of homeland warfare in 1864, and the outcome of his military actions was uncertain.

Lincoln had trusted in many Generals, including William Tecumseh Sherman, who had invaded deep into Mississippi and Dixie.

Sherman was closing in on Atlanta, Georgia, with the bulk of the United States Army in August of 1864.

Sherman’s supply lines were fortified in many areas of Tennessee, but in many other areas, it was weak.

He was concerned about his lines of communication and sustainability deep into hostile, enemy territory.

In January 1864, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest returned to north Mississippi after the Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia.

Forrest raised a new cavalry in the area here, in Oxford, Como, Okolona, Columbus, Grenada, West Tennessee, and all parts in between.

Forrest’s army was extremely mobile, and he was able to defeat much larger forces at various areas in Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Kentucky.

Some of Forrest’s most famous engagements in the area include West Point, Okolona, Shiloh, Brice’s Crossroads, Harrisburg, Fort Pillow, Oxford, Memphis, and Paducah.

In 1864, North Mississippi was Nathan Bedford Forrest territory.

Forrest won many victories through impressive scouting, proper deception, cunning adaptability, complete surprise, and thorough, decisive actions.

Forrest was the bane of existence for the Union army, and no one could defeat him.

Union General Sherman was wisely concerned about the ability of Forrest’s Cavalry to invade Middle Tennessee and cut off his United States Army from supply lines and bases in the North.

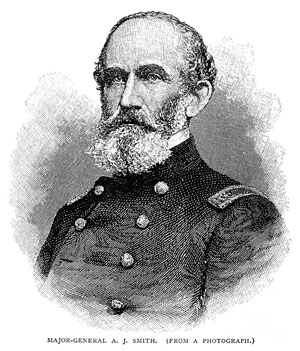

Sherman directed a new army lead by Andrew Jackson Smith to convene near Memphis, Tennessee.

Their purpose was to coax out Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate Cavalry from hiding in North Mississippi.

The Mission? Seek and Destroy!

Smith’s army of 15,000 made it as far as Pontotoc County before being challenged by Forrest, who was headquartered at Okolona.

From Pontotoc, Smith’s Army jettisoned to what is now Tupelo, in an area once known as the hamlet of Harrisburg.

The Union dug in and the Confederate forces under Generals Stephan D. Lee and Forrest attacked. The Battle of Harrisburg took place on July 14–16, 1864.

A.J. Smith claimed victory at Harrisburg, while retreating back to Memphis from Confederate forces.

General Forrest did suffer a gunshot wound to the foot, and he retired to the Golden Triangle area to recuperate. His cavalry spread throughout the region.

Sherman was not impressed. Neither was General Ulysses S. Grant or President Lincoln.

“I will order them to make up a force and go out and follow Forrest to the death, if it cost 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury,” General Sherman wrote.

“There never will be peace in Tennessee till Forrest is dead.”

A.J. Smith was ordered back into Mississippi immediately from Memphis, this time with 14,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.

While Forrest was tending to his foot wound in Okolona, he was unable to ride a horse with both feet in the stirrups.

When Smith’s army reached Holly Springs in early August 1864, General Forrest had no choice but to ride in a buggy to Oxford, while his 5,300 troops fortified the area.

Confederate General James Chalmers and the local boys in the 18th Mississippi Cavalry Battalion fortified North Lafayette, Marshall, and Panola Counties, around the Tallahatchie River and Hurricane Creek.

Smith decided to use the railroad from Holly Springs to get his troops to Oxford. This was the exact route that Grant had taken in 1862 when he invaded Lafayette County with his 40,000 troops.

Grant destroyed the railroad when he retreated, including the bridge over the Tallahatchie. Smith’s troops would have to repair the rails and bridges as they fought the Confederates, and advanced towards Oxford.

General Chalmer’s troops dug in deep in Marshall and Lafayette County, and the Confederate cavalry fought well.

But it wasn’t enough.

Forrest and his Escort arrived on the Oxford Square and quickly surmised the situation.

His Confederate troops were outnumbered, battered, and bruised, including himself.

Forrest was convinced that his troops would not be able to fight such a large force straight on, so he devised a plan to lure the Union army out of North Mississippi by boldly attacking their home base, Memphis, Tennessee.

General Forrest took about 2,000 cavalry troops and high tailed it from Oxford to Memphis, by way of Panola County, Mississippi.

Forrest got back into the saddle, but with only one foot in the stirrups.

General Chalmers cavalry held their own against the larger Union Army by pretending to be a much larger Confederate force. Surprisingly, A.J. Smith had no idea of Forrest’s Confederate troop movements in this area.

Forrest’s cavalry rode into Memphis, Tennessee on August 21, 1864 and Union troops there were completely caught off-guard.

Memphis had been under Federal control for most of the Civil War without serious resistance and they certainly weren’t expecting to be attacked.

Forrest’s raid was deep into the heart of the Union controlled city and he killed and captured about 400 Union soldiers, and nearly caught General Cadwallader Washburn in the process. Forrest high tailed it back to Hernando, Mississippi almost as fast as he invaded Memphis.

A.J. Smith was bogged down fighting with Confederate forces dug in at Hurricane Creek, in Lafayette County.

Smith was relieved to finally drive them from their fortifications, but by the time he reached Oxford, his supply line was stretched.

Smith was relieved to finally drive them from their fortifications, but by the time he reached Oxford, his supply line was stretched.

As General Smith took over the Oxford Square, he learned of Forrest’s attack on Memphis and realized that he was not fighting a large Confederate Cavalry, or even Bedford Forrest.

General Smith had been outwitted, and the attack on Memphis was completely embarrassing for the Union army. He was now in danger of being attacked by the Confederates on two sides.

Enraged, Smith ordered Oxford to be burned and the scene quickly devolved into absolute chaos.

Chaplin Elijah E. Edwards of the 7th Minnesota kept a diary and sketchbook during his time in Smith’s army and he described the scene in Oxford:

“I saw everywhere scenes of riot and the wildest confusion. Many houses were in flames, and others were being plundered relentlessly by the mob consisting of mostly of soldiers, without guidance but acting as any unruly mob would do. They carried from the buildings all kinds of plunder most of which could not be any use to them. They carried mirrors, rocking chairs, vases, articles of wearing apparel, bedding, books. As the smoke grew denser the scene grew more weird and more like Hades. This piece of diabolical tomfoolery was capped by an exhibition that would scarcely be deemed possible, in a CIVIL war. A drunken man on horseback came galloping through the smoke, holding before him a grinning skeleton which he had stolen from a Doctor’s office. It is said that this vandal was a Surgeon’s Assistant. Whoever he was, and I did not want to know more, his act was the most revolting that I have to chronicle.”

Smith’s army marched out of town to the glow of a canopy of flames. Oxford was destroyed. There were no more businesses, supply depots, warehouses, no courthouse, and nearly every house in the area was torched.

Several buildings at the University of Mississippi were spared as they were being used as a hospital for soldiers of both armies.

The Episcopal Church near the Square was also spared and a handful of houses were saved, too.

But Oxford was a ghost of its former self and those citizens and soldiers who had fled the town in the wake of the arrival of the Union army had nothing to return to.

A.J. Smith never talked about why he ransacked and burned Oxford, but it is clear to most observers that his actions were in retaliation from being outwitted by General Forrest.

If an army took this type of action today, it would probably be considered a war crime.

Smith’s actions and the drunken rioting of his soldiers earned him the nickname “Whiskey” by both the local citizens and the Rebel soldiers.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was never defeated or caught by the Union army and his cavalry continued the fight for another ten months.

When Forrest learned of General Robert E. Lee’s defeat and surrender at Appomattox in 1865, Forrest and his cavalry finally surrendered at Gainesville, Alabama on May 9, 1865. ![]()

Related: “Jacob Thompson: One of Oxford, Mississippi’s, and the South’s Most Wanted Confederates”

This article originally appeared in The Local Voice #210, August 14, 2014. Download the PDF of this issue, click here. It’s free.

© 2014-2023 The Local Voice – Rayburn Publishing