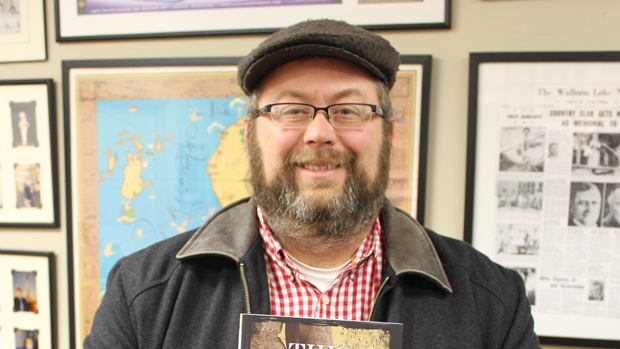

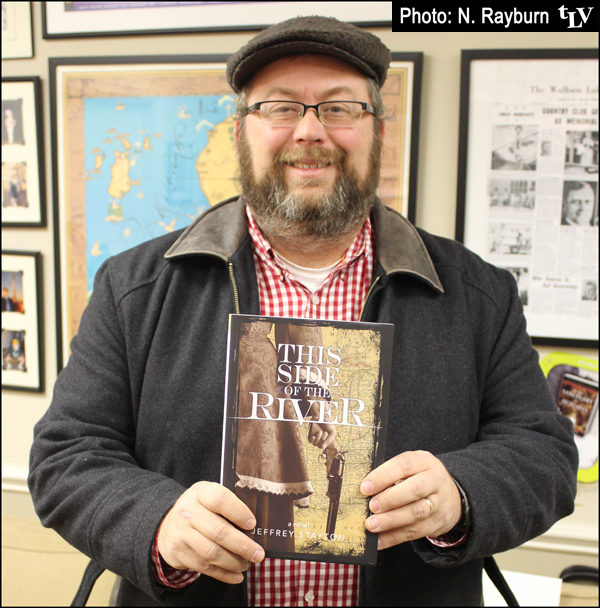

Ole Miss Professor Jeffrey Stayton publishes his first book, a Civil War novel of nostalgia, redemption, and a posse of women hell-bent on revenge.

by Newt Rayburn

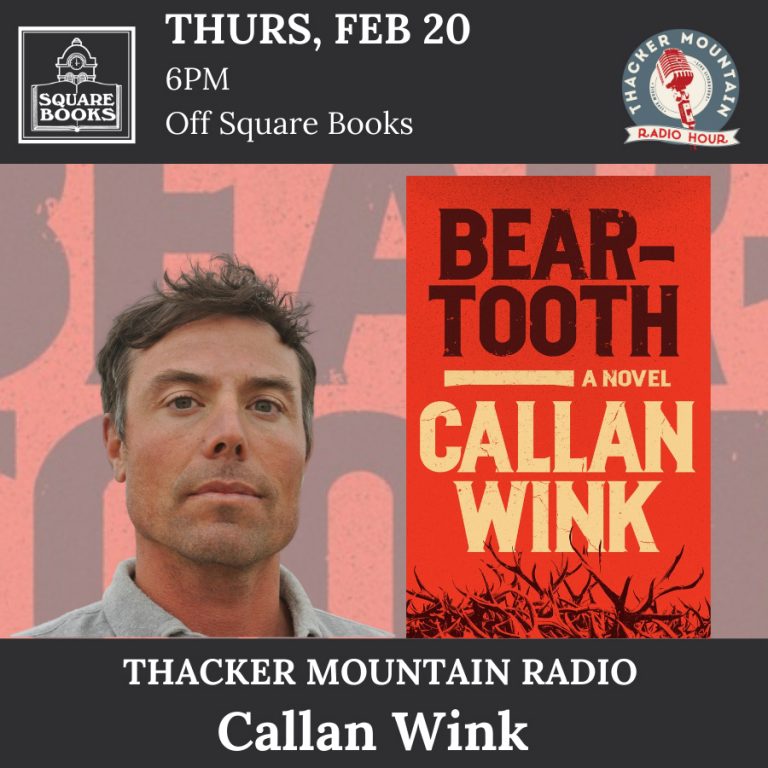

Coinciding with the Sesquicentennial of the end of the Civil War, Ole Miss Professor Jeffrey Stayton is set to release his first novel, This Side of the River, February 15 on Neil White’s Oxford-based Nautilus Publishing Company.

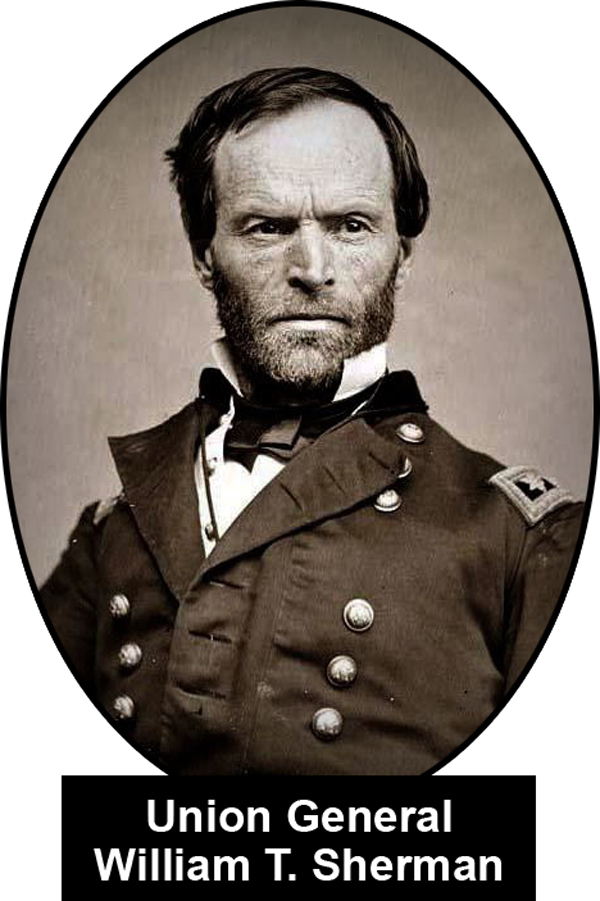

Stayton’s fiction is set in summer of 1865, after the collapse of the Confederacy. Told from the perspective of multiple narrators, the story chronicles a group of widowers from Georgia who are mad as hell at Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, after losing everything but their lives during the infamous Sherman’s March. The women form a posse and decide to travel to Lancaster, Ohio, for the purpose of giving the General a taste of his own warfare and seek to burn down his home. Stayton’s tale explores themes of trauma, revenge, redemption, and the disorder known as “nostalgia,” or “soldier’s heart.”

Stayton’s fiction is set in summer of 1865, after the collapse of the Confederacy. Told from the perspective of multiple narrators, the story chronicles a group of widowers from Georgia who are mad as hell at Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, after losing everything but their lives during the infamous Sherman’s March. The women form a posse and decide to travel to Lancaster, Ohio, for the purpose of giving the General a taste of his own warfare and seek to burn down his home. Stayton’s tale explores themes of trauma, revenge, redemption, and the disorder known as “nostalgia,” or “soldier’s heart.”

Jeffrey Stayton grew up in Texas, but eventually moved to Mississippi and earned a Ph.D. in English at Ole Miss, where he currently teaches. Stayton lives in Midtown Memphis, Tennessee and commutes to Ole Miss to teach. Jeffrey is a scholar of Modernist, Southern, and African-American literature, often teaching women’s literature courses as well. When he’s not teaching or writing, Stayton can be found in his Midtown studio working on oil paintings, a passion that was renewed after hiking 500 miles on the Camino de Santiago in Spain.

Stayton writes poetry, has written reviews for The Missouri Review and has published stories in StorySouth, Lascaux, and Burningword Literary Journal. His original story “Pepper” won the Bondurant Award for Fiction, and his story “Chisanbop” appeared in the Best of Carve Magazine.

Stayton spent eighteen years writing and rewriting This Side of the River. During that time he spent many hours researching Civil War history, battles, and diaries. Jeffrey travelled the South to Civil War hot spots and retraced General Sherman’s March through Georgia and the Carolinas.

An audio book of Jeff’s novel is also under production now, featuring locals Rory Ledbetter, Darby Burghart, Rachel Stayton (no relation), and Whit Hubbard, as well as actors from the Hattie Lou Theater and Chatterbox Audio Theater in Memphis.

Jeffrey Stayton will be reading and signing copies of his novel at Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi. The signing was scheduled for Monday, February 16, 2015 but was cancelled due to weather conditions. It has now been rescheduled for Monday, March 2 at 5 pm.

What drew you to writing about the Civil War?

What drew you to writing about the Civil War?

I’m a Faulkner scholar; when I first read Faulkner over twenty years ago, I was fascinated by his version of the Civil War. I grew up in Texas and usually Texas history kind of supersedes anything like the Southern roots of Texas—it’s all cowboys and ranching more than anything Civil War related. But that whole trauma Faulkner wrote about really fascinated me. It showed up obviously here where I’m writing about the aftermath of the Civil War. Part of what drew me in was reading novels like A Light in August, where you can just see the shambles that their whole lives are afterwards.

I had a really good history professor of the Civil War named Alwyn Barr. He was great because he exploded a lot of the myths that usually were kicked around—that it was just some states’ rights issues, if it was a football game, and he was like, “No.” Every argument he could trace back to slavery in this matter-of-fact way, so any of the mythology was kind of taken out of the equation as I was doing my research. He taught at Texas Tech. He was a Civil War scholar; he also wrote an amazing work on black Texans’ history, and he started getting me fascinated about black cowboys as well. There’s a slave from a cattle ranch who’s a cowboy, and that shows up in [the novel]. I’m really indebted to a lot of professors I’ve had over the years, whether they’re creative writing instructors or scholars, because they really had an impact.

I understand that you travelled to a lot of Civil War sites in Georgia.

I did a whole driving tour of Sherman’s March—Atlanta to Savannah—but also through the Carolinas. You have something as simple as the hoofmarks embedded in a small church in some small town in Georgia, because the officer decided to stable his horses [there]. Little details like that were really important to pick up on. And I got the lay of the land in a way that you just can’t do any other way.

I’ve found that with the Civil War, it’s one thing to read about it, it’s another thing to go there and see where it actually happened.

Obviously Shiloh, because this is where my central character, Cat Harvey, goes through the battle when he’s a teenager and gets the shellshock, which was called nostalgia or soldier’s heart back then. Scouting out that whole well-preserved battlefield was really amazing. I even brought my wife out there, and she doesn’t have much of an interest in the subject necessarily, but she really appreciated it.

Everything changed when I stood on that battlefield. You were talking about PTSD, how does that relate to this book and the Civil War?

After 9/11, I had a talk with my father, whom the novel’s dedicated to, about whether I should drop out of graduate school if they call for troops and enlist, which is something I was kind of cagey about. But that was such a shock. I had a neighbor who [said], “It’s like Pearl Harbor all over again.” He was a World War II vet, and I [thought], “Alright, what do I do?” My dad [encouraged] me to ask questions and hold off on running out and signing up. So, while there’s quite a number of people who were able to forget about Afghanistan and Iraq and things going on there, I’d stay up on it. The thing that really struck me is that you had troops coming home [who], because of advances in medicine, survived their wounds; whereas before they’d have been dead. On the one hand, that was a good thing. On the other hand, you had these wounded warriors suffering post-traumatic stress disorder and it was something that I got really fascinated with, because the one thing that Civil War histories—whether they’re memoirs or letters—they’re not able to talk about that. Because of the language of honor and glory, they have to mask a lot of that stuff. When I read about the regiment that Cat Harvey is from, Terry’s Texas Rangers, it was like wholesale slaughter at Shiloh.

They were using Napoleonic tactics with back-then modern weaponry, so horses and soldiers alike were just butchered. So that got me thinking. You’re supposed to think of war in these particular terms, but war in fact is waste. Or as Sherman said, ‘It’s all hell.’ So how do you reconcile those two things? As I kept reading, I discovered about a death squadron, kind of like a black ops organization called Shannon’s Scouts. There are a few websites on them, and what little diaries they kept, they were doing a lot of extermination against Sherman’s bummers during the march—it was really a horror show. I thought, “How would a teenager metabolize all that? Committing war crimes?” That’s what led me into those directions—different soldiers would come home, and you hear about the suicides, or about them committing crimes, or acting out in domestic violence, and all sorts of horrific stuff. That’s something I was aware of in a way that I probably wouldn’t have been had I not been giving it serious thought after 9/11.

Re-examining that idea with the Civil War?

Yes, just kind of filling in the blanks. In the 19th century, if you admitted that you suffered those traumas then you were admitting you were a coward instead of actually admitting you were wounded—you were suffering a brain injury or simply doing something that we’re not supposed to be doing, which is killing and being killed, and some things that go against why we’re here on earth, I think.

You read a lot of Civil War diaries. Could you find that in there?

Yes. For instance, I have a whole box of material I collected from various archives, whether it was county archives, or the Austin State Archive, or various other places, and I got obsessive with all of it, and it was great. It was like a huge jigsaw puzzle that I wanted to piece together, and I even created a document where five days out of every week of the Civil War, I knew what the regiment I was researching was doing. The diaries are where you usually experience a little more honesty. [In] the memoirs, there would be an awareness that it’s a public statement of the regiment, and so you get different levels. What was really affecting was a guy named Frank Bachelor and his brother-in-law, George Turner. They join the regiment and go through maybe three years of the Shilohs and the Chickamaugas, and everything in between, and then George dies of camp sickness. That’s how most people died for the longest time—not so much on battlefields, but in the sick towns. The tone in Frank Bachelor’s letters goes from having a heroic spin on things, trying to make sense of the war in optimistic terms, to [losing] his best friend—brother, really—and how do you go on? Things like that give you access to what’s in the heart of a lot of these men. They really thought that they were fighting a second independence, they thought it originally was going to be over [in] like six months, and [they’d] be home by Christmas. They had no idea what they were getting into. Then, of course, by the end, with Sherman’s March, you inaugurate total war, and you have black ops that they’re participating in.

So that’s where your novel picks up, at the end?

So that’s where your novel picks up, at the end?

Yes, at the end of the war. I didn’t think it was going to be a post-Civil War novel. For the longest time it was Civil War, and I was doing all this writing related to that, until my dad read Cold Mountain. I think he’s the only one in America who’s somewhat dissatisfied by it, and I was intrigued. I’ve taught it; I think it’s a really great Civil War novel. So I [said], “Really Dad, why didn’t you like it?” What I gathered was that he read the back cover and had a different idea of what it was going to be, but when I pushed him a little, he said something really amazing. He [said], “I wanted a novel about what happened after these guys were done. How did they get home?” If you’re stuck in North Carolina and you’re trying to get back to Louisiana or Texas, what goes on along the way? I started chewing on that, and what was an 1861 novel flipped into a month-after-1865 story. That’s where I started seeing the shape of this one, where I had Cat Harvey and some of the guys he’s with; what they did back then was discovered the gold, which gets talked about in this novel. That whole world is kind of post-apocalyptic. I’m a McCarthy fan, too, so I enjoyed that kind of tone. That’s another reason I dedicated it to his memory—because he’s my dad, but also he was the one who really set me on a path for telling this story.

I noticed right off the bat that every chapter has a different narrator, which is very interesting.

It’s funny, the mosaic style. As I Lay Dying is obviously the most famous of that, but another novel I really love is Feast of Love by Charles Baxter, and he does that [style] as well. In this novel, you have people who show up for half a page and disappear forever, or you have widows who might recur four or even seven times in short chapters. I like that kind of style, it’s almost like theatre in the round. It made the most sense to me, and I was able to sustain it. I really enjoyed, too, [that] the portrait of Cat Harvey is fragmented, fractured, and kind of has the feel of a cubist painting, which is who he is. So I really felt like that form was the way to go, even though there are characters in there I would love to find out their full stories. My wife, who is a writer as well, wants to write about Darkish Llewellyn—and I kind of like the idea of her taking over and telling the full story of Darkish.

Without giving away too much about the book, does the posse ever make it to Ohio?

Here’s what I’ll say: They make it to Ohio, alright. And General Sherman narrates the last chapter.

And that’s all I’ll say.

And you are a painter? Would you consider that your main art, or is it more of a hobby?

I hiked northern Spain with my wife; it was her dream to do the Camino de Santiago, and it was like six weeks covering 500 miles. You get insights when you go on that kind of a pilgrimage, and you have a different mindset because you’re taken out of your norm. Some of them are not very deep, but some can be pretty profound. [For me], one of them was that I’d been working on writing as my primary identity, primary objective, for like 25 years, and painting and art had kind of taken a back seat. While I was hiking, I was thinking, “Why am I not making more time for this?” So I kind of like the idea that maybe this is the only novel I write. Maybe this is enough and [I’ll] at least take a victory lap with the book tour and anything else that comes about before I think about cranking out another one. So the time I used to spend writing, I’m now spending in my art studio in midtown, in the Cooper-Young area. It’s funny, it’s this thing I loved when I was a kid and did obsessively. Somewhere in the teenage years it got put off to the side and never went away, and I never had a good reason for it. I had to get my head clear just to examine that.

Herman Payton did the cover art for your book?

I believe so.

I know him from way back. He used to hang out at the Hoka Theatre. It’s a beautiful cover, but I was kind of curious why you didn’t do some art for it.

That was the funny thing. We had this idea, Neil [White] and I, and my wife helped with the cover as well. I really love looking at the old tin-types that soldiers would take of themselves—usually early in the war—you didn’t have time or energy for that sort of stuff by the end. Usually as they’re about to leave for future battles, they take some type of tin-type of themselves with their firearms. So we liked the idea of doing something similar with that. We got [Brooke and Ashley Fly] together for a photo shoot. I guess it was this weird kind of 19th century Charlie’s Angels for a little while, but we actually got a lot of great shots.

Who do you think will most appreciate this book and want to read it?

Actually I have this hunch that the grumpy old men who like the typical Civil War fiction might pick it up and then think, “This is not what I thought,” because they’re looking for a football game version of events. I think that either their wives who are better read or their teenagers who want something more subversive might pick it up, and that [could] actually be where it carries. I was a student of Barry Hannah and Tom Franklin, and I think this is very Smonk-ish—I don’t know if Tom would want me to say that, but he blurbed it—and [it has] that kind of carnival-esque version of events, I think. I’ll tell you this much, I listen to not a whole bunch of old-timey Civil War songs to get me in the mood. I listened to 1970s and 1980s heavy metal. I used to be in a metal band when I was a kid, and that put me in the mood. So I’d listen to some Black Sabbath here, or I’d listen to Iron Maiden’s “Children of the Damned,” with my coffee and everything else, just hit the keyboard from there.

What kind of metal band were you in?

I think Guns ‘N’ Roses was our favorite band, but we didn’t approximate them, we just did what we could. We still talk and I’m going to give them copies of my novel.

What was the band called?

High Treason.

Where were you from?

Houston. We never made it out of Montgomery County. But it was almost like my first love. Some people had a girlfriend in high school…my girlfriends were great, but my band, we just had all that passion and breakups, and the bromance, or whatever you want to call it. My wife wouldn’t let me bring drums into the home, I kind of miss them.

You’re also doing an audio book. Tell me the characters you’re narrating.

I’m doing three of the narrations: Smit Harvey, who’s a drunk, a gambler, and he would rather be in the 17th century—and that was a lot of fun to do.

I also narrated the Ringmaster, who—I would give too much away if I try to explain who he is—but that was a lot of fun, being him. I also narrated Sherman.

I hired actors in Memphis and Oxford, and even one in Tupelo, and they’ve been great. Rory Ledbetter did Ethan Briarstone, which was a really important part, plus two of his students—Rachel Stayton (no relation), and Darby Burghart. Rachel’s doing Brianna O’Quinn, so she has an Irish brogue; I was lucky to find her. Darby is doing Darkish Llewellyn, which was a very hard part for me to cast, just because my wife loves that character so much and I can’t miss-cast it, otherwise I’m sleeping on the couch. So they’re connected with Ole Miss. Whit Hubbard also read a part, he’s an instructor in the English department, and he’s a writer as well, so I gave him a small part that he had a lot of fun with, too.

In Memphis, Hattie Lou [Theater] Actors, Chatterbox [Audio Theater] Actors, played different parts. The only one I had to farm out was a friend of mine in Ithaca, New York, [who] is a really good actor. I was having a really hard time finding Uncle Calsas, the black cowboy, who’s about 60 years old, and I said, “Do you want to try it?” He nailed it, and I was so grateful, because that was a very hard part to cast.

When does the audio book come out?

I’m hoping it’ll be April or May. We’re wrapping things up in February. I love it—it’s been a lot of fun. It’s the closest I’ve ever felt to being a film director. There are all these moments where the brutality or whatever, the emotional stuff that I wrote about—I wasn’t detached writing it, but the register of it sometimes hits me when the actor or actress is performing. So something that maybe I should have felt while I was in the business of writing and revising finally hits home; that’s been an amazing process.

When I started reading the book, I was thinking that it would be a great short film or something. You get a feel for the characters right away.

That would be the best thing, seeing what would happen. How to film it? That would be the hard part. And my name’s on it, so I would be very picky about whose hands it would be in, but that would be great. Little Game of Thrones money. Neil [White] would be really happy with that, too. ![]()

–

This is the extended version of an interview which was originally printed in The Local Voice #222 (published February 5, 2015.)

To download a PDF of this issue (also the extended interview), click here.