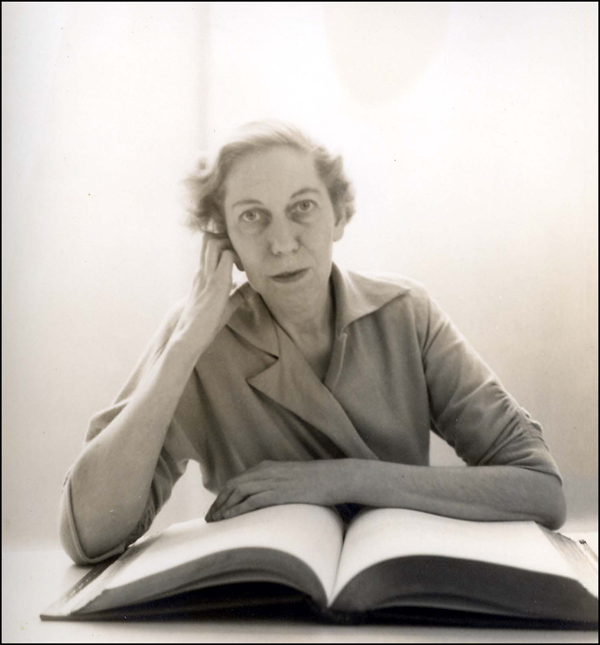

While preparing last issue’s column on Eudora Welty (Local Voice #223), I cast a wide net for anecdotes about the Mississippi author of such enduring tales as “The Optimist’s Daughter,” the 1972 Pulitzer winner for fiction.

Once deadline had passed, two pieces to the puzzle emerged: one from the stacks of the Library of Babel in a book by another great female writer—the Canadian expatriate Mavis Gallant (1922–2014); the other via e-mail from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

I was introduced to Gallant through her obituary last February and added her to my 2015 discipline to only read female authors.

In the introduction to Gallant’s story collection Varieties of Exile (New York Review Books, 2003), Russell Banks writes “… less than a handful of living story writers are her equal: William Trevor, and Gallant’s countrywoman Alice Munro, perhaps, and—since the death of Eudora Welty—no American that I can think of.”

Which is to say that when it comes to Americans who had practiced the art of the short story there was Welty and then there is everyone else. If you have the right adversary, say a champion of John Cheever, that wouldn’t be a bad game of literary badminton as we wait out another dreadful winter.

And then, Danny Heitman got back to me from Baton Rouge, where he writes for The Advocate, the daily paper in the capital of the Pelican State.

Heitman interviewed Welty at her home on Pinehurst Street in Jackson on a hot, glaring July day in 1994, about seven years before her death at age 92. Last year, he profiled the author in Humanities magazine.

Heitman interviewed Welty at her home on Pinehurst Street in Jackson on a hot, glaring July day in 1994, about seven years before her death at age 92. Last year, he profiled the author in Humanities magazine.

One of the things that caught his attention—the idea that all good narrative flows forward even when a writer digresses—was also mentioned by Banks as part of Gallant’s genius.

Heitman noted it with a passage from Welty’s 1984 memoir, One Writer’s Beginnings, which spoke of an apprenticeship that began before young Eudora had committed to the Vocation (yes, capital V) of storytelling.

She remembered: “In our house on North Congress Street in Jackson where I was born, the oldest of three children … we grew up to the striking of clocks. There was a mission-style oak grandfather clock standing in the hall which sent its gong-like strokes through the living room, dining room, kitchen, and pantry, and up the sounding board of the stairwell.

“Through the night it could find its way into our ears ….”

Welty then mentioned that her parents’ had a second clock—smaller, similarly striking—“that answered it.”

This was a good lesson for a future writer of fiction, she observed, “being able to learn so penetratingly … about chronology. It was one of a good many things I learned almost without knowing it; it would be there when I needed it.”

It was a lesson which Banks believes Mavis Gallant knew as well, whether learned or intrinsic.

Gallant, he pointed out in the same introduction that lauds Welty, keeps “the story flowing, like a meandering stream crossing a broad plain to the sea, like consciousness.”

I have yet to discover enough about Mavis Gallant to know much about her except that, like Welty she tended to be quiet and reserved. What most people didn’t know about Eudora, said Heitman was “the wry edge to her humor.”

I have yet to discover enough about Mavis Gallant to know much about her except that, like Welty she tended to be quiet and reserved. What most people didn’t know about Eudora, said Heitman was “the wry edge to her humor.”

Looking back on his visit to her house—now a museum—some 20 years ago, he said that she had taken to “using one of those lift chairs with a mechanical cushion that rises up to help convalescents to their feet.

“She told me it was a bit like an ejector seat, and that she occasionally wished for one over on the sofa, to help get rid of the company.”

At the time Welty confided this, Heitman was sitting on the sofa.

“Her meaning was subtle yet clear,” he said. “It was my cue that our interview had gone on too long.” ![]()

–

This article was originally printed in The Local Voice #224 (published March 5, 2015.)

To download a PDF of this issue, click here.

1 thought on “Eudora the Great and Humble Pt. 2”