Three musicians are huddled around one another with their collars turned up in an attempt to appease the bitter cold wind that was cutting right through them.

Clear Lake, Iowa, is an unforgiving environment in February. The warmth of the Surf Ballroomis behind them, as was the admiration of the fans who turned out to see them perform on the latest stop of “The Winter Dance Party.”

Earlier that night, in a side room off the stage, a young 17-year-old Californian singer and guitar player was dreading returning to a broken-down tour bus with no heat for a 365-mile journey even farther North.

The word spread quickly that the Texan, whom most fans came out to see, was chartering a plane to avoid what was sure to be a frostbitten drive. In 11 days of the tour, 5 separate buses had already been in use, causing the gang of musicians to label this as the “tour from hell.”

The youngest member of the tour approached the veteran hired guitar player, who had been assured a seat on the flight for a price of $36, and asked if he could possibly have his seat. The flu was starting to work thru his body, and he was feeling it. The singer/songwriting DJ from Beaumont, Texas, had it as well, but had been given his seat by another touring member of the band.

The youngest member of the tour agreed to a game of chance. A coin toss. The plane would seat three plus pilot, and two of the spots were already taken, so he accepted the odds, despite an innate fear of flying, and with a simple flip of a coin, won the coveted last seat. The three cold and tired musicians climbed aboard the Beechcraft Bonanza at Mason City Municipal Airport shortly before 1am and flew into the history books of rock and roll.

Hubert Jerry Dwyer, the owner of the plane, became concerned that morning when the pilot had not made contact with him since takeoff. He embarked in another of his aircraft, to retrace the flight plan of the missing Bonanza. After seeing what he thought was the plane, Dwyer contacted the sheriff’s office. Deputy Bill McGill drove in his cruiser to a field owned by Albert Juhl northwest of the airport where he found the mangled pile of metal and carnage that had carried, at the time of its crash, three of the top-grossing musicians in the country.

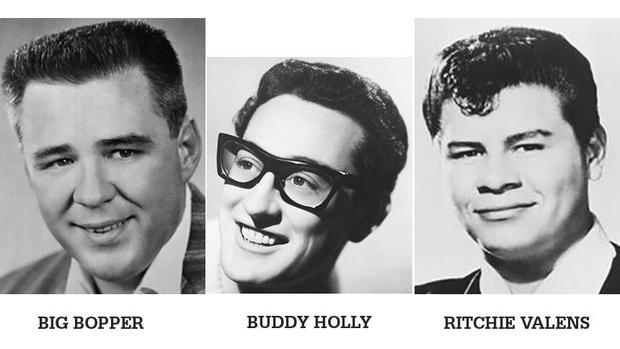

In the early morning hours of February 3, 1959, 22-year-old Texan rockabilly hero Buddy Holly, 17-year-old Chicano singer Ritchie Valens, and 28-year-old DJ and songwriter, J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson along with 21-year-old pilot Roger Peterson, died in a frozen cornfield less than six miles from their departure in what came to be known as “The Day the Music Died,” immortalized by the Don McLean 1971 hit “American Pie.”

This year marks the 60th anniversary of this tragic plane crash that claimed the lives of three musicians with multiple number one hits to their name.

Valens, the youngest of the three, was fresh off his first appearance on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and a role in DJ Alan Freed’s movie Go, Johnny, Go! The year before his fateful joining of “The Winter Dance Party” tour, Valens had a million-copy selling single with his ballad “Donna,” penned for his girlfriend of the same name.

Holly’s luck had seen a downturn after leaving his band The Crickets. Plagued with lawsuits from former promoters, owed royalties by his former manager, and being freshly married, Holly had but one chance to make some much needed money, and that was to do what all musicians do—tour.

Richardson, who had a hit with his tongue-in-cheek song “Chantilly Lace,” had just recently taken leave from his disc jockey duties to go on the road for the first time to promote his new single.

Assembled for this tour to back up the artists was a band consisting of Waylon Jenningson bass, guitarist Tommy Allsup,and drummer Carl Bunch. The tour was set to cover twenty-four Midwestern cities in as many days. It began in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on January 23, 1959.

The amount of travel soon became a logistical problem. The distances between venues had not been properly considered when the performances were scheduled, which led Holly to his fateful decision that night in Iowa, to charter a plane and fly ahead to the next stop, to get some well-deserved rest before the next performance.

The intended passengers that night were Holly and his band members, Jennings and Allsup, but Richardson was ill with the flu and Jennings gladly gave his seat to the boisterous son of a Texas oil field worker.

Valens, who had a terrible fear of flying that stemmed from a childhood friend’s death, was on the verge of falling ill as well, and asked guitarist Allsup if he could have his seat on the warm plane. This led to the fabled toss of a coin and Valens, with a “heads,” assured his seat. Years later in his native Texas, Tommy Allsup, in honor of the 17-year-old rock pioneer, opened a restaurant he simply called The Heads Up Café.

There are all kinds of misconceptions about that night. The most common is that it was Waylon Jennings who flipped with Valens for that last seat. Jennings holds a much darker and unfortunate distinction in this series of events. When Holly learned that Jennings had given his seat to Richardson, Holly jokingly said “Well I hope that ole bus freezes,” to which Jennings replied, “Yeah well I hope your plane crashes”—astatement that he would regret for the rest of his life.

The Civil Aeronautics Board, which handled accidents like this before the formation of the National Transportation Safety Board, descended on the cornfield in Iowa to start the investigation into how these three musical heroes perished, while county coroner, Ralph Smiley, had the most of unfortunate jobs in determining the exact cause of death of the four young men.

Holly and Valens had both been ejected from the plane and lay nearby. Peterson, the 21-year-old pilot, was still in the twisted and battered wreckage of the fuselage. Richardson’s body had been thrown from the wreck and almost 100 feet across a fence and into a neighboring field. Smiley assessed that all four men died instantly from “massive brain and chest trauma.”

The CAB investigators estimated that the Beechcraft Bonanza had attempted to turn when the right wing clipped the ground, at 170mph, causing the plane to cartwheel into the field for over 540 feet.

The young pilot had logged 711 hours of flight time with 128 on this particular type of aircraft, along with 52 hours of what is known as “instrumental flight.” During this training, a pilot learns to fly and navigate using only his aviation instruments and no sight, the kind of skills needed to circumvent the conditions that night in 1959.

A light snow was falling with a ceiling of 3,000 feet, sky obscured, and visibility was six miles with winds from 20 to 30 mph. Although deteriorating weather was reported along the planned route, the weather briefings Peterson received failed to report that. Despite his instrumental training, Peterson had not passed the needed written examination to be certified in this discipline, and he was only licensed to fly under visual flight rules.

To further complicate the already doomed situation, the training he had received was on a different model Beechcraft, with an opposite set of instruments, including the more modern artificial horizon as a source of aircraft attitude information, while the plane he was piloting that night was equipped with an older-type Sperry F3 attitude gyroscope.

Crucially, the two types of instruments display the same aircraft pitch attitude information in graphically opposite ways. In the cold dark of Clear Lake that night, with no ground lights for guidance in the sparsely populated farm areas, no visible horizon and low clouds, the young pilot made a fateful decision to take to the skies.

In the aftermath of the crash, news spread quickly of the stars’ demise on the newswire. The headlineof the Mason City Globe Gazette that day read “Four Killed in Clear Lake Plane Crash.” News stations and reporters flocked to the crash site. Journalism in 1959 was not policed by the guidelines that we adhere to in this day and age, regarding deaths and releasing the names of the victims until next of kin has been notified by law enforcement first.

In New York City, Holly’s bride of only six months, María Elena learned of his death on a breaking news report, breaking down and suffering a miscarriage upon hearing of Holly’s death.

Bob Morales, Valens’ older brother was working on a car a few blocks away from his mother’s house, when a local DJ broke in with the news of the crash. Bob ran to the house, not wanting to believe what he had heard. As he opened the door, his worst fear had come true as he saw two of Ritchie’s friends on either side of their mother, holding her up. “Bobby, we lost your brother,” she said.

Adrienne Joy Richardson, 7 months pregnant, with her 5-year-old daughter in tow, was attempting to get the days grocery shopping done when she was approached by a friend in the market wanting to express her deepest sympathies in her husbands passing, of which she had no knowledge.

The CAB investigation determined in due time that the cause of the crash was “the pilot’s unwise decision” to fly in those conditions that night, without proper training, leading directly to the crash. Funerals were held for Holly in Texas, Valens was buried in California, and Richardson was laid to rest in Beaumont.

Holly’s widow, María, did not attend his funeral.

Donna Ludwig, the 16-year-old blonde high school student who was the muse for Valens’ million selling single “Donna,” mourned her first and true love.Donna and Valens had met at a garage party where Ritchie was playing. It was love at first sight. They shared two and a half years of memories before his untimely passing.

Two months after the crash, Adrienne Richardson gave birth to her and JP’s second child, a boy, named Jay Perry Richardson in honor of his father. The world mourned in unison for the loss of these song and dance men, who all had so much more music to share with an eager audience.

The day after the crash in New Rochelle, New York, a 13-year-old music fan folded his papers to be delivered that crisp morning and learned of his idols passing and like the rest of the country, it was an event that would set itself deep into his memory as turning point in his own life.

In 1971, the now 26-year-old musician, Don McLean wrote and recorded what was to be his opus in the song “American Pie.”In his touching tribute to his heroes, McLean exorcised the pain of the memory from that February morning 12 years prior.

“Something touched me deep inside, the day the music died,” and with that lyrical turn, he gave a name to the tragedy which is still attached to it some 60 years later and turned an entirely new generation onto the music of the three rock stars depicted in his ode.

It has been six decades since the day the music died. In those long years, the lives of those pioneers of rock, rockabilly, and country have been immortalized in many ways.

In 1978 actor Gary Busey gave an Oscar-nominated portrayal of Holly in TheBuddy Holly Story. Valens was paid tribute to in the Golden Globe for Best Drama award-winning film La Bamba staring Lou Diamond Phillips and featuring music from fellow Chicano rockers and Valens contemporaries Los Lobos.

There are numerous tributes and monuments to the trio within their hometowns, with streets and highways named for them and at the crash sight there is an even a plasma-cut steel set of Wayfarer-style glasses like those Holly wore.

Countless musicians from John Lennon and Paul McCartneyto Dwight Yoakam and Los Lonely Boys, all count Holly, Valens, and Richardson as influences and inspirations of theirs. When the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, inducted its first group of performers, Holly was among those tributed, and in 2001 Valens was recognized as an inductee as well.

Richardson, despite penning country legend George Jones’ first number one smash “White Lightning” and the Sonny James hit “Running Bear” along with his own top ten hits and with being credited as making the first music video ever in 1958 for “Chantilly Lace” has been snubbed by the Rock Hall.

Most people today know the crash and those involved, from the movies, songs and Broadway plays based on their short but meteoric rise to fame, but keeping their memories alive, in any shape or fashion, assures us that the next generation of children who pick up a guitar will never forget the trio of musicians who paved the way for so many us to pursue that ever consuming passion that we call music.