Article & Photos by Rebecca Long

As a teenager, I swore I’d leave Mississippi one day, move to a “cooler” place—I had almost no pride in my home state because we’ve been so close to last on so many lists. After a few years living in Oklahoma, though, I moved back to the Delta in my early twenties, and my attitude changed almost immediately. The weekend after I got back to my hometown of Greenwood and got settled in, there was a free Blues festival scheduled in Whittington Park. What the heck? I thought. There’s nothing else to do on a Sunday in Greenwood.

The Blues changed my life, beginning that weekend. It was exactly the right time in my life to get introduced to this “old-timey” music from my stompin’ ground. I think people’s tastes in music change over time, and if I’d tried to listen to the Blues before that weekend, I doubt I’d have found it as profound and as important as it really is. I finally began to understand that the Blues is truly American music, and that so many other types of music draw heavily from the Blues. And I was learning that this all started in my home state, right down the road.

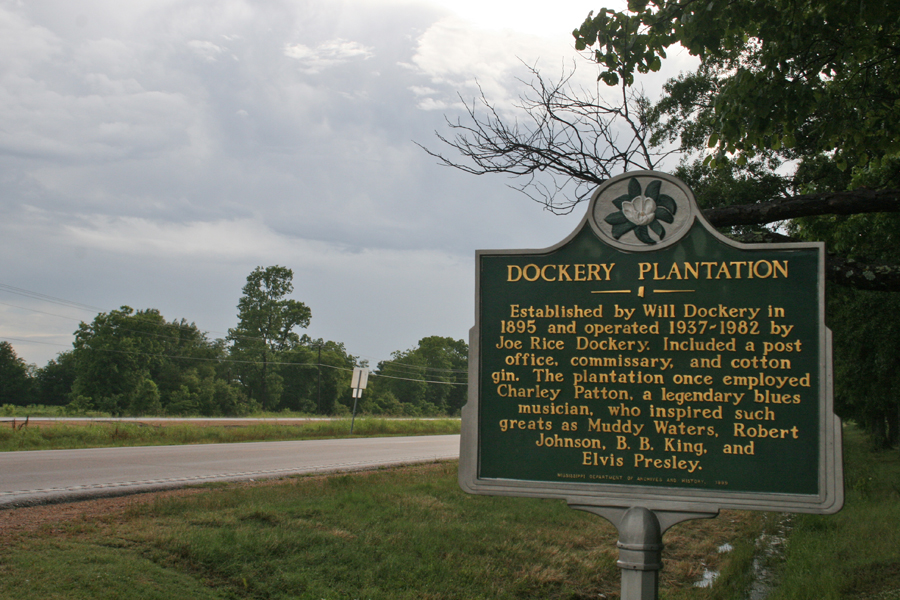

On the day of that fateful 2002 festival in Greenwood, I met a handsome hobo Blues musician from Seattle, Bobby “Blues” Rutledge. We began dating soon thereafter, and in the time I spent with him, he showed me things in my Mississippi Delta I didn’t know existed. On one trip to Clarksdale, years before the Mississippi Blues Trail was established, he directed me to drive through Tutwiler to see the spot W.C. Handy was first sitting when, as legend has it, he heard a lone guitarist who struck his heart’s chords so loudly that Handy became known as the “Father of the Blues.” He took me to Dockery Farms; on the way he explained that Charley Patton, “King of the Delta Blues,” had learned to play guitar in this tiny once-plantation-town. Soon thereafter we went to a tribute for Patton in Holly Ridge; the guitarist spent his last year there and is buried beside Willie James Foster and Asie Payton.

On the day of that fateful 2002 festival in Greenwood, I met a handsome hobo Blues musician from Seattle, Bobby “Blues” Rutledge. We began dating soon thereafter, and in the time I spent with him, he showed me things in my Mississippi Delta I didn’t know existed. On one trip to Clarksdale, years before the Mississippi Blues Trail was established, he directed me to drive through Tutwiler to see the spot W.C. Handy was first sitting when, as legend has it, he heard a lone guitarist who struck his heart’s chords so loudly that Handy became known as the “Father of the Blues.” He took me to Dockery Farms; on the way he explained that Charley Patton, “King of the Delta Blues,” had learned to play guitar in this tiny once-plantation-town. Soon thereafter we went to a tribute for Patton in Holly Ridge; the guitarist spent his last year there and is buried beside Willie James Foster and Asie Payton.

Even long after Bobby moved away I was attending Blues festivals and learning what I could about these musicians who invented out of the doldrums and necessity new ways to play the guitar, whose lyrics came from real-world strife (not the invented, first-world troubles so many of today’s “musicians” sing about). If there’s one thing I learned from my friend Bobby about the Blues, that was it: the Blues isn’t happy—a lot of it comes from the musicians actually living through the hardships they sing about. If you listen, the strife creeps through in the dark places of the songs.

I love the Blues. And I love driving down backroads in Mississippi. The Delta is my favorite place to drive, too, so at the beginning of May I planned to go on a road trip visiting Blues Trail markers I hadn’t seen yet. The weather was icky then, so I decided to just take photos of the sites around Greenwood, where I happened to be visiting family. The remainder of the trip finally got re-planned when I found out about the May 31 gravestone dedication ceremony for T-Model Ford in Greenville. Having seen T-Model play more times than I can count, I still get emotional when I think about his death, and I found myself really wanting to attend the ceremony. (Note: I didn’t realize until I started putting this story on the web that the first time I ever saw T-Model play was on that fateful Sunday in Greenwood!) I invited my best friend Golda/Ellie McLellan to accompany me and figured we could go see all the Blues trail markers on my list before the 4 pm dedication ceremony.

Hardly anything about the trip went as planned and we got fairly soggy with rain, but we still had an enjoyable time. At T-Model’s ceremony I had an epiphany about the Greenwood sites I had visited a month prior, and while my comrade and I learned about the Blues, we learned even more about the state of our home state.

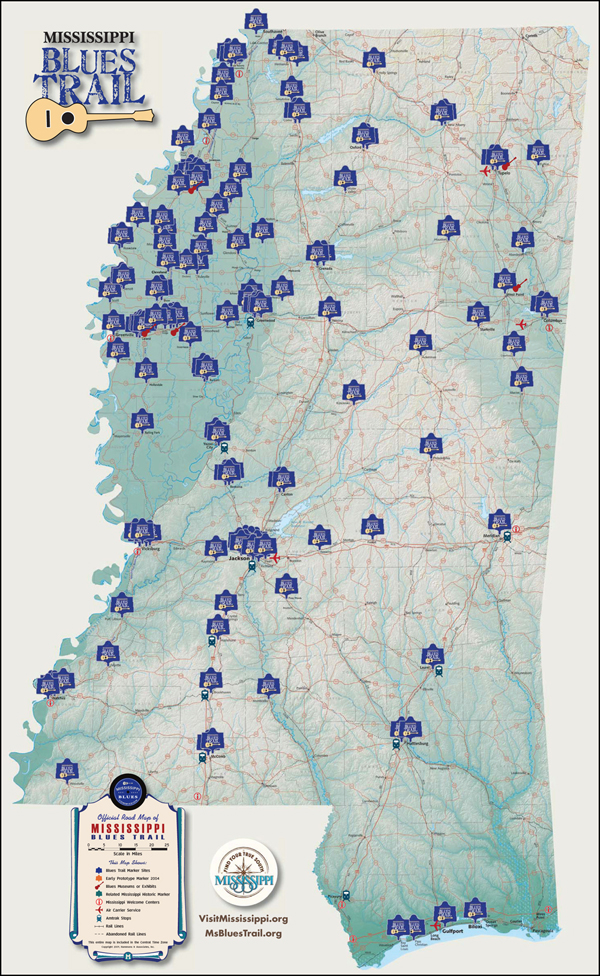

First of all, the number of markers is remarkable—at last count there are 165 markers scattered across the state, and 11 more out of state. (You can visit www.msbluestrail.org for a list of markers and info about each one.) When I was deciding what route I would take to get from Oxford to Greenville, I became really thankful for Google Maps. It displayed that I basically had three routes from which to choose; it estimated that each route would take almost exactly the same amount of time, so it wasn’t an easy decision. The first of the three would have taken me through Greenwood (where I’d already been). The second route would have had us heading West on Highway 6 through Marks and then South on Highway 49, passing through towns with markers like Tutwiler and Ruleville, and hitting Highway 82 in Indianola to see all the B.B. King markers. But I chose the third route, with the markers I most wanted to see: we headed West on Highway 6 through Clarksdale, and then South on Highway 61 until we finally hit Highway 82 in Leland.

My advice is to have an entire day for this trip—it’s easy to misjudge how long your adventure will take, and it’s a lot less fun if you’re rushed. A great idea Nature Humphries had was to drive down to the Delta on one highway and return on another, to maximize the number of markers you might see. And take some music —the radio stations in the Delta are fairly awful (though we heard perhaps the most amusing religious ad ever, since my CD player is broken).

On our way to Greenville, there was little of interest until we got closer to Clarksdale. I had decided to see if The Dutch Oven in Clarksdale was open; we were famished and this Mennonite-run restaurant has amazing food. A lesson you can learn from our trip is: The Dutch Oven is closed on Saturdays and Sundays. But if you do get to eat there, I recommend the Reuben, and you shouldn’t skip the pie!

I hadn’t planned to stop in Clarksdale at all until my hunger got the best of me—exploring all the Blues history in that one town can take all day! But I figured as long as we were downtown we would stop in Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art, because Ellie had never been. I describe Cat Head (not related to the vodka) as kind of like a “home base” for Blues enthusiasts. Owner Roger Stolle is usually there and it’s always good to see him. This time, however, Preston Rumbaugh was running the shop and telling a group of teenagers all about Charley Patton.

I hadn’t planned to stop in Clarksdale at all until my hunger got the best of me—exploring all the Blues history in that one town can take all day! But I figured as long as we were downtown we would stop in Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art, because Ellie had never been. I describe Cat Head (not related to the vodka) as kind of like a “home base” for Blues enthusiasts. Owner Roger Stolle is usually there and it’s always good to see him. This time, however, Preston Rumbaugh was running the shop and telling a group of teenagers all about Charley Patton.

Ellie and I browsed for a few minutes and as I listened to Rumbaugh talk I realized these kids would be on the same part of the Blues Trail as us—he was drawing them a map to maybe the most important Blues site of them all, Dockery Plantation. I paid for my bumper stickers and when asked, told Rumbaugh why we were headed to Greenville. We left “home base” and had what should have been a quick lunch across town. When we were done eating, I realized exactly how little time we had before the 4 pm ceremony. We headed straight to Greenville from Clarksdale, not stopping once, and were still fifteen minutes late.

Ellie and I browsed for a few minutes and as I listened to Rumbaugh talk I realized these kids would be on the same part of the Blues Trail as us—he was drawing them a map to maybe the most important Blues site of them all, Dockery Plantation. I paid for my bumper stickers and when asked, told Rumbaugh why we were headed to Greenville. We left “home base” and had what should have been a quick lunch across town. When we were done eating, I realized exactly how little time we had before the 4 pm ceremony. We headed straight to Greenville from Clarksdale, not stopping once, and were still fifteen minutes late.

We did arrive late for a ceremony that was fairly short, and moments after the gravestone was unveiled the rain began. One of the awesome things about the Delta is that you can see the weather coming and going from miles away, because the land is so flat. We knew it would start to storm soon, and I needed to visit more trail markers to finish this story, so we opted out of going downtown for the reception and headed back down the Blues Trail. The weather cooperated for the most part—it rained cats and dogs on the way to our first stop but slowed to a drizzle when we got to Leland.

We did arrive late for a ceremony that was fairly short, and moments after the gravestone was unveiled the rain began. One of the awesome things about the Delta is that you can see the weather coming and going from miles away, because the land is so flat. We knew it would start to storm soon, and I needed to visit more trail markers to finish this story, so we opted out of going downtown for the reception and headed back down the Blues Trail. The weather cooperated for the most part—it rained cats and dogs on the way to our first stop but slowed to a drizzle when we got to Leland.

The Highway 61 Blues Museum was closed when we arrived but it’s a pretty cool place; the Blues Trail marker for James “Son” Thomas stands in front of it and the Johnny Winter marker is across the street. Around the corner is the “Corner of 10 & 61” marker, with a wall of Blues folk art beside it. The rain stayed calm through our visit to the graveyard in Holly Ridge. I paid my respects to Charley Patton and headed back up 61 towards Clarksdale.

The Highway 61 Blues Museum was closed when we arrived but it’s a pretty cool place; the Blues Trail marker for James “Son” Thomas stands in front of it and the Johnny Winter marker is across the street. Around the corner is the “Corner of 10 & 61” marker, with a wall of Blues folk art beside it. The rain stayed calm through our visit to the graveyard in Holly Ridge. I paid my respects to Charley Patton and headed back up 61 towards Clarksdale.

Then the bottom dropped out. The rain made visibility really poor but luckily it let up before we went through Shaw. While headed through town to find the marker we saw a train painted on a building’s outer wall. Not only in Leland and Shaw but in other towns too, notably Clarksdale, the towns embrace Blues tourism with art like this—look for it! As I was driving up to the Blues Trail marker in Shaw for Honeyboy Edwards, I saw a place called “Bear’s” with guitars and music painted on the outside so I snapped a picture. The guy who had been sitting on the porch asked me why I was taking pictures and I told him I once saw Honeyboy play in Clarksdale and that I respected him a lot. He said “Alright” and seemed less affronted, but he guy sure scowled when he first saw me.

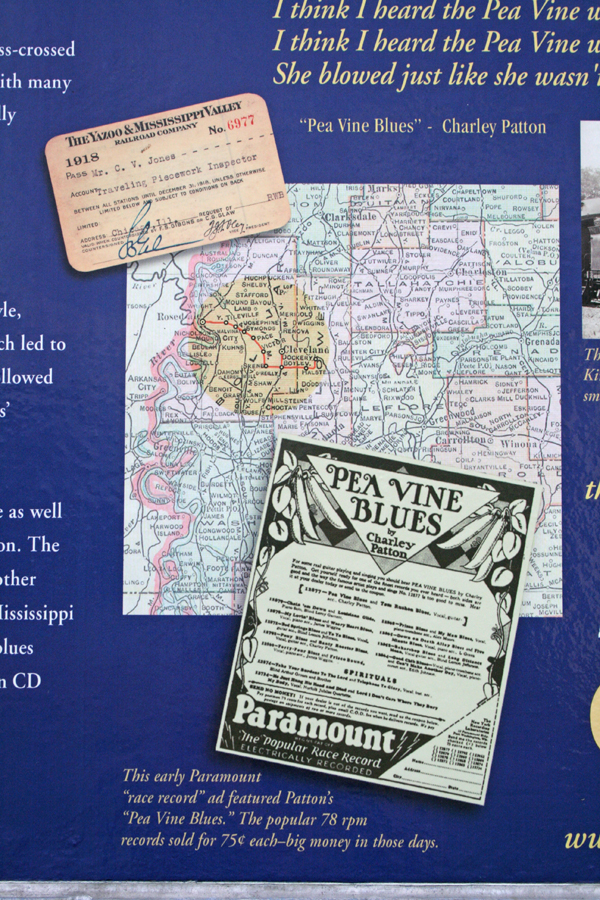

Next we visited the marker for “The Peavine” in Boyle. Charley Patton made this railroad branch well-known with his song “Pea Vine Blues,” which is a great tune with lyrics that have always touched me: I cried last night and I ain’t gonna cry no more, cause the good book tells us you got to reap just what you sow. Stop your way of livin’ and you won’t have to cry anymore. Patton has always had my heart as “King of the Delta Blues,” even though I’m from Greenwood and it would make sense for me to be a champion for Robert Johnson since we spent time on the same stompin’ ground. So this turned out to be an unintentionally Patton-centric trip; I only wish I’d had his music playing while we drove around.

Next we visited the marker for “The Peavine” in Boyle. Charley Patton made this railroad branch well-known with his song “Pea Vine Blues,” which is a great tune with lyrics that have always touched me: I cried last night and I ain’t gonna cry no more, cause the good book tells us you got to reap just what you sow. Stop your way of livin’ and you won’t have to cry anymore. Patton has always had my heart as “King of the Delta Blues,” even though I’m from Greenwood and it would make sense for me to be a champion for Robert Johnson since we spent time on the same stompin’ ground. So this turned out to be an unintentionally Patton-centric trip; I only wish I’d had his music playing while we drove around.

After we left Boyle, we arrived in Cleveland and veered down Highway 8 so we could go to Dockery Plantation, where Charley Patton spent so much time in his younger years (around 1900). Since I last visited ten years ago the site’s changed a little. I don’t remember the “Dockery Service Station” out by the road having such a shiny paint job, but it looks nice. There’s a guestbook now, protected from the rain, and mounted signs direct visitors to check out www.dockeryfarms.org.

After we left Boyle, we arrived in Cleveland and veered down Highway 8 so we could go to Dockery Plantation, where Charley Patton spent so much time in his younger years (around 1900). Since I last visited ten years ago the site’s changed a little. I don’t remember the “Dockery Service Station” out by the road having such a shiny paint job, but it looks nice. There’s a guestbook now, protected from the rain, and mounted signs direct visitors to check out www.dockeryfarms.org.

And of course, the Blues Trail marker at Dockery reads “Birthplace of the Blues?” There’s a button installed right behind the trail marker; when depressed it plays Patton’s “Spoonful Blues” and other tunes through speakers all over the farm. It was fun to tromp around Dockery, but after we left there we were soggy and ready to return to Oxford. We made one last stop in Alligator, and I not only learned that Robert Johnson once lived there, but that Robert “Bilbo” Walker called Alligator home at a young age. If you ever get the chance to see Walker, he puts on a heck of a show.

And of course, the Blues Trail marker at Dockery reads “Birthplace of the Blues?” There’s a button installed right behind the trail marker; when depressed it plays Patton’s “Spoonful Blues” and other tunes through speakers all over the farm. It was fun to tromp around Dockery, but after we left there we were soggy and ready to return to Oxford. We made one last stop in Alligator, and I not only learned that Robert Johnson once lived there, but that Robert “Bilbo” Walker called Alligator home at a young age. If you ever get the chance to see Walker, he puts on a heck of a show.

Ellie and I talked about our trip the following day, and we took away similar feelings from our foray into the Delta. She said some poignant things, and one statement that truly resonated is, “I felt like a tourist in my home state.”

What’s important to see when you visit sites on the Blues Trail is the Delta itself. The men from these tiny towns who became well-known because of their music had a lot to sing about poverty and living conditions. And if you take a good look around you’ll see that not much has changed in many of these places. I once edited a sticker that read “I Believe in the Delta” with a new phrase: “I Used To Believe in the Delta,” and I’m ashamed of ever thinking that way. Please realize as you head out of Oxford on your way to the Delta how beautiful and well-maintained things here are, and how much stuff you have access to. When you arrive in the Delta, notice the lack.

What’s important to see when you visit sites on the Blues Trail is the Delta itself. The men from these tiny towns who became well-known because of their music had a lot to sing about poverty and living conditions. And if you take a good look around you’ll see that not much has changed in many of these places. I once edited a sticker that read “I Believe in the Delta” with a new phrase: “I Used To Believe in the Delta,” and I’m ashamed of ever thinking that way. Please realize as you head out of Oxford on your way to the Delta how beautiful and well-maintained things here are, and how much stuff you have access to. When you arrive in the Delta, notice the lack.

I missed Anthony Bourdain’s recent Parts Unknown episode filmed in Mississippi, but I read what he had to say about our state and he was right on target: “It’s a poor state—and investment in infrastructure—whether renovating your home, modernizing your restaurant dining room, redeveloping an abandoned section of town is not much of a priority or even an option much of the time. So it looks much as it did in the movies you’ve seen. That’s both curse and blessing. If you are focused on change? You will likely be frustrated. But if you like the good, old school shit—you will find it in Mississippi.”

At least one Yankee gets it. What about all the other privileged Blues enthusiasts who visit our state, though? Do they think the poverty is just for show? I read a lot of comments recently on a blog of photos taken in Greenwood’s “Baptist Town” which amounted to this: people from the outside have no idea how underprivileged a lot of communities are in the Delta, and they think the residents should just pull themselves out of it through sheer willpower…like there are jobs to be had…like the education system there isn’t completely screwed up. But those are subjects for another article, and I get overly passionate about them.

At least one Yankee gets it. What about all the other privileged Blues enthusiasts who visit our state, though? Do they think the poverty is just for show? I read a lot of comments recently on a blog of photos taken in Greenwood’s “Baptist Town” which amounted to this: people from the outside have no idea how underprivileged a lot of communities are in the Delta, and they think the residents should just pull themselves out of it through sheer willpower…like there are jobs to be had…like the education system there isn’t completely screwed up. But those are subjects for another article, and I get overly passionate about them.

I haven’t given up on the Delta, but there isn’t much I can do about most of the residents. But thinking about all this hit me especially hard when I tried to narrow my thinking to a Blues musician I knew: T-Model Ford didn’t live like a rich man. He certainly didn’t have a lot of money towards the end. If it weren’t for the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund—including Euphus “Butch” Ruth (amazing Delta photographer), “Skip” Henderson, and T. DeWayne Moore, plus Ford’s friends Amos Harvey, Alan Orlicek, and Rob Mortimer, where would T-Model’s bones be resting right now? Thank the gods for those guys, and for the Blues Benevolent Committee and Music Maker Relief Foundation who have helped artists like T-Model over the years. Without the generosity of men like these, who knows what would have happened to some of our most beloved musicians? Please keep your eyes open when you go to the Delta and remember what the Blues is all about.

I haven’t given up on the Delta, but there isn’t much I can do about most of the residents. But thinking about all this hit me especially hard when I tried to narrow my thinking to a Blues musician I knew: T-Model Ford didn’t live like a rich man. He certainly didn’t have a lot of money towards the end. If it weren’t for the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund—including Euphus “Butch” Ruth (amazing Delta photographer), “Skip” Henderson, and T. DeWayne Moore, plus Ford’s friends Amos Harvey, Alan Orlicek, and Rob Mortimer, where would T-Model’s bones be resting right now? Thank the gods for those guys, and for the Blues Benevolent Committee and Music Maker Relief Foundation who have helped artists like T-Model over the years. Without the generosity of men like these, who knows what would have happened to some of our most beloved musicians? Please keep your eyes open when you go to the Delta and remember what the Blues is all about.

–

Full Photo Gallery:

Where can I get Bobby ‘Blues’ Rutledge Cds? I heard him sing “Crossroad Blues” in 2001 in Greenville, MS in 2001 and saved a small CD I purchased from him and just found it but it will not play. Best version I ever heard!

Phil