GEDSC DIGITAL CAMERA

Flying through the night and deep into the following day on beer and reefer and Charlene’s diet pills (she never took them, carried about 220 pounds on a barrel frame, not a halter-top in the country up to the challenge) Willie drove 16 hours straight hours from Baltimore to Memphis, driving the Monte Carlo into a broken-hearted city about dinner time on Wednesday, just about the time Cherry was waking up from a nap on the wrong side of the tracks.

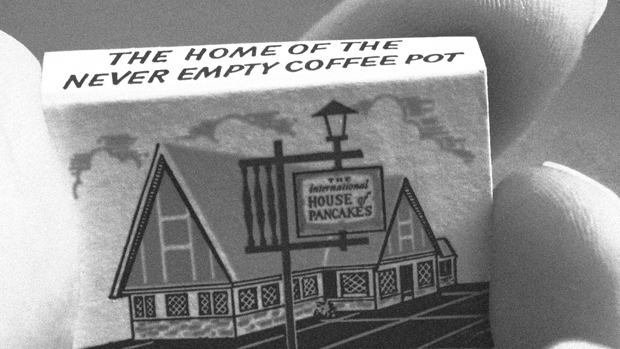

Sixteen hours and 900 miles later, the teenager passed out at the steering wheel ten seconds after turning off the ignition in the parking lot of an International House of Pancakes not more than two miles from Graceland.

Charlene left Willie slumped across the front seat of the car as she went in for her first meal since late the night before that didn’t come from a gas station. The place was packed—a zoo AND a circus and nothing close to what was brewing on the streets—and it ratcheted up her despair with her hunger.

Charlene left Willie slumped across the front seat of the car as she went in for her first meal since late the night before that didn’t come from a gas station. The place was packed—a zoo AND a circus and nothing close to what was brewing on the streets—and it ratcheted up her despair with her hunger.

“Just one,” said Charlene, scanning the packed restaurant, looking forward to a tall stack of buttermilk flapjacks with fried eggs, toast, and a double side of bacon, hoping she might see somebody famous to take her mind off of the loss of the most famous. “Anywhere you can squeeze me in is fine.”

The red-neck who picked up Cherry in Humphreys County some 150 miles ago drove right past the IHOP where the Monte Carlo sat parked for hours. The driver even pointed the place out, said he used to mess around with a waitress who worked there, laughed lewdly and made a joke about pancake syrup, but since the parking lot was around back, all Cherry saw was a line of people waiting to get in.

On that parking lot, Willie was so deep in his bottom-fell-out-of-the-amphetamines exhaustion that he slept for six hours as Charlene went back to graze the fixins bar, coffee and pie and more coffee to wash it down and decided to “walk it off”—“Christ, she told Willie later, “was I BLOATED!”—heading north on Highway 51 to Graceland on foot.

“Be careful honey,” said the waitress, recognizing kinship in the washed-out, 30-year-old peroxide blonde from the hillbilly section of South Baltimore. “The pick-pockets and muggers are having a field day with all of this carrying-on.”

“It’s a goddamn shame,” said Charlene, leaving a generous tip.

“Don’t ya know, darling?” said the waitress, clearing the table. “Whole world’s gone crazy.”

Cherry and his quarry—the 16-year-old he called brother, a distinction determined solely by the generosity of the woman who’d raised them as siblings—were never more than five miles away from one another as Memphis swelled by 100,000 pilgrims over the day leading up to the funeral.

Cherry and his quarry—the 16-year-old he called brother, a distinction determined solely by the generosity of the woman who’d raised them as siblings—were never more than five miles away from one another as Memphis swelled by 100,000 pilgrims over the day leading up to the funeral.

Cherry didn’t see Willie or the Monte Carlo that he hoped to take from the teenager, not at first anyway, but as he wandered the city in search of flesh and metal and eventually shelter—not long before dawn on Thursday—he did see a drunk driver of a 1963 white Ford Fairlane leave the highway and ram a crowd holding candles outside of the Music Gates.

The man’s name was Treatise Wheeler and after watching the Fairlane slam, drag, and mangle two young women to their deaths and nearly maim a third—lipstick and chewing gum and house keys from their purses strewn along the roadway—the crowd began chanting for the driver to be lynched.

At which point Cherry went to find a tree to slump beneath for some shut-eye, using his canvas satchel to rest his head.

Did he dream beneath the great magnolia?

Yes, something about going to see a drag race by the ocean with Judy Apicella.

Did he remember the details?

Not really, needle-nosed dragsters flashing by like arrowheads, the relentless surf and Judy as she looked six years ago when he took piano lessons from her in a church group at Our Lady of Pompeii, the church where they had her funeral Mass after her husband shot her in the kitchen, the .22 bullet going through her body and into the still-open refrigerator where it shattered a jar of pickles as easily as the Fairlane had smashed Tammy Baiter, Alice Hovatar and Juanita Johnson.

In about five hours, a hundred cargo vans would begin delivering flowers to Forest Hill cemetery, a train of coaches and limousines and policemen on horseback that surely, thought Cherry as he fell in and out of sleep—“You messed me up, Judy, you really messed me up…”—would include a gold 1970 Monte Carlo with a black vinyl roof. ![]()

–

Previous Installments of “Cherry in Magnolia”:

Part 1: Who Died and Made You Elvis

Part 2: Getting There Is Half The Fun

look for Part 4 in TLV #232

–

This article was printed in The Local Voice #231 (published June 11, 2015).

To download the PDF of this issue, click here.

Wonder-filled, very evocative writing. Love the imagery and the crazy, humbly human characters.