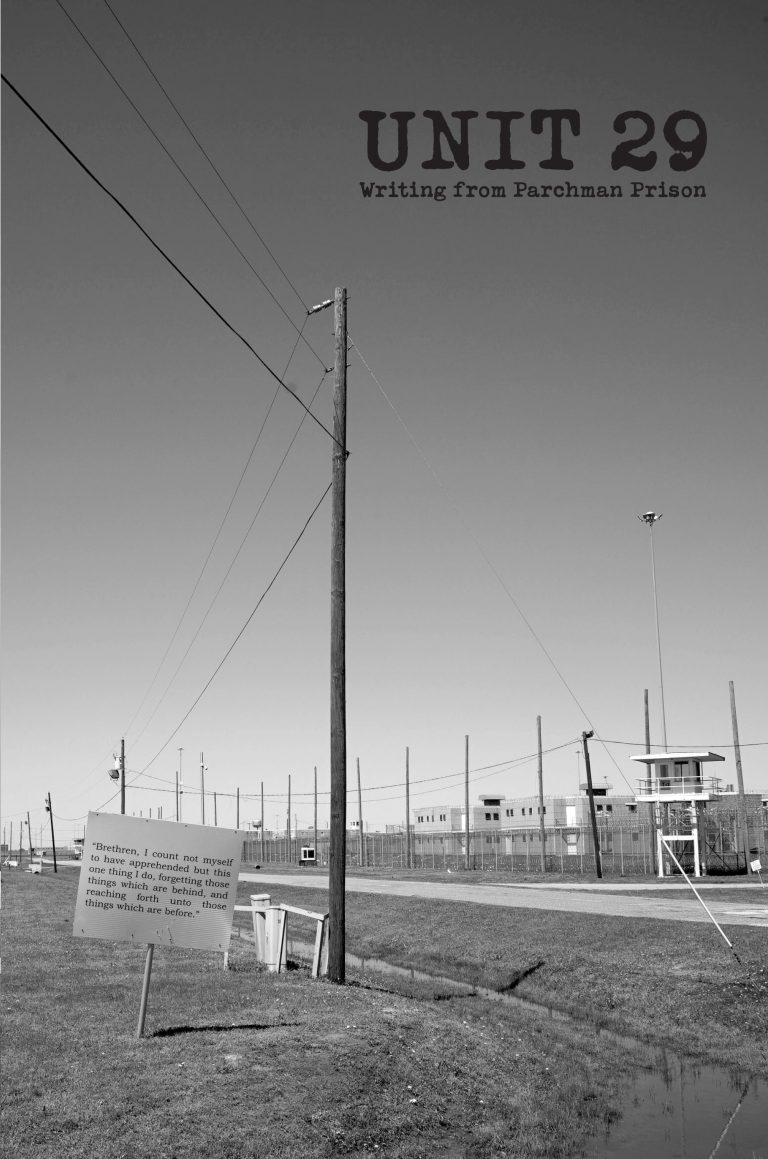

GEDSC DIGITAL CAMERA

“And my head is my only house unless it rains…” – Don Van Vliet

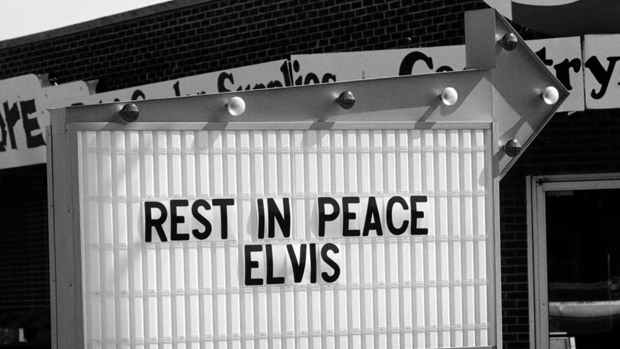

Willie had just lost his lover, to whom he’d lost his virginity before leaving Baltimore 48 hours ago (driving all night to pay respects to the King,) and he’d lost the car that carried them there, a gold Chevy for which he’d just gotten his license; turning from the rail on the Memphis & Arkansas bridge—moments after Charlene jumped into the river—to see that it was gone.

But the only thing the cop driving him to the police station for questioning wanted to know was also lost on him.

“If there is a car and we find it, what do you think we’ll find in it?”

Willie, 16 and a long way from home: “What?”

“What’s in the car you’re reporting stolen?”

“Flowers.”

“You a liar or a sissy boy?”

“From the funeral,” said Willie, staring at the Mississippi through the dirty window in the back of the cruiser. “Vernon said we could take as many as we wanted.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Cherry left the Monte Carlo parked behind the Kroger (it was in Arkansas and his problem was in Tennessee), locked his satchel and squeeze-box in the trunk and took a cab to the police station, asking the driver where a vagrant might be taken if he were picked up on the bridge.

“All depends,” said the cabbie.

“If he were a stupid white kid from out-of-town who couldn’t find his ass with two hands and a map, where would they take him?”

“South Main,” said the driver.

“Go there.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Cherry was waiting in a park across the street from the police station when, about four hours later, pushing close to 10 pm, Willie walked out of the building looking dazed, exhausted, inconsolable, and afraid.

Cherry got up from his bench near a statue of Nathan Forrest and his horse and walked toward the street, approaching his little brother who, standing curbside, stood immobile, staring at his dirty red and blue high-top Converse, as lost as the Confederacy.

“Willie,” whispered Cherry, crossing the street.

Willie, who had not seen the pie-anna player for three years; Willie, dumbfounded, the boy who had named his by-nurture-but-not-by-nature brother “Cherry,” back when Elvis starred in Kid Galahad, Cherry because the toddler could not say “Jerry” nor tell a lie.

Startled back to reality, eye-to-eye: “Where’s the car, Cherry?”

“Let’s go, Ace.”

Anger, a river runs through it: “Where’s the car?”

Cherry put his crippled hand on Willie’s shoulder—leggiero—and gently guided the boy away from the police station.

“I’ve got the car, which you would not have right now if I hadn’t taken it.”

“Charlene jumped.”

“I saw it.”

“You think she’s…?”

“Yes. Come on, let’s go home.”

“Where’s home?”

“Where do you think, dumb-ass? Come on, let’s go see Ma.”

“I can’t.”

Silence.

“They’re going to find her. They’re searching. I need the car to drive her home when they find her.”

“It’s a Monte Carlo, not a hearse, Will. And I’m only here because Ma told me to find you. Let’s go.”

“No.”

Cherry took $20 out of his pocket and gave it to Willie, who took it and said, “I don’t need money, I need the car.”

“Sorry,” said Cherry, and he meant it. Good Lord, was he ever this stupid, even when he was taking lessons with Judy in middle school?

“Drive to Baltimore with me and you get the car. Stay here looking for a sunk barge, shit Will, you get what you get.”

Willie jerked away from Cherry and cursed him with a venom that went all the way back to playing kickball in the alley; with all the frustration for the pain the older boy had caused Ma with his lying and thievery, the humiliation when Judy Apicella’s husband threatened to burn down their house when he found out Cherry had been sleeping with his wife, when Cherry’s explanation to Ma had been: “She taught me how to roll a bass line with my bad hand…”

But he didn’t go back into the police station to tell them what was going on.

The second time Willie cursed Cherry the musician walked away from his little brother and instead of getting a cab (the $20 he’d given Willie was the last of his cash), began walking back to the Kroger on the other side of the river, strolling past the spot on the bridge where Charlene had jumped and pausing not to pray or remember or feel bad for his brother but to think about what he might tell Ma when he pulled curbside on Iris Avenue in a day or two with the car but not her only biological child.

He played out a few scenarios, spit into the river—unable to see it land in the darkness or hear it hit the current—and made his way to the Arkansas side, the cover of darkness and a route north through Missouri to protect him from a police search for a vehicle they didn’t believe existed.

Cherry had a good friend in St. Louis, a singer he’d met on Frenchmen street. She’d put him up long enough to figure out what to tell Ma. ![]()

Part 1: Who Died and Made You Elvis

Part 2: Getting There Is Half The Fun

Part 3: Wednesday, August 17, 1977 – All Hopped Up and Ready to Go

Part 4: Thursday, August 18, 1977 — Sixteen Coaches Long

Part 5: Smooth, Fast & In High Gear