GEDSC DIGITAL CAMERA

[Editor’s note: This is an extended version of the interview found in TLV #238 with Jon Langford. Enjoy!]

–

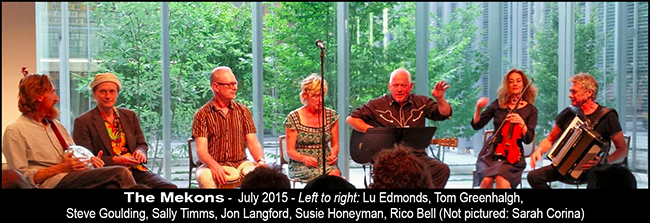

Jon Langford is a Welsh-born musician and artist who currently resides in Chicago. He is perhaps best known as a member of influential punk band The Mekons, though he has been involved in numerous other groups (The Waco Brothers, Pine Valley Cosmonauts, etc.). Langford is also a politically outspoken individual, and has campaigned against the death penalty in Illinois. A selection of his visual art is currently on display at The Powerhouse.

I noticed it was interesting group of artists and musicians that Sarahfest has brought in, because we have so many people who have been politically vocal and active. Just to get the ball rolling, could you comment on the state of women and gender in the arts these days? Is that something that you think about?

Well, you know, I’m in The Mekons, and The Mekons have always been a mixed band, with men and women in prominent roles. I think it’s kind of like there was some kind of barrier that got kicked down with punk rock around that time. It was very unusual for women to be in rock music, other than being the lead singer or the backing vocalist. While it’s not commented on that much now, that was something that was kind of fundamental [then]. It’s not such a big novelty. Yet, having said that, I still think there’s so much further to go in all stratas of society. As a male feminist, I still think it’s kind of scary how society reverts to its stereotypical posturing.

Right. It’s interesting how you have things crop up in music that are experiencing a renaissance for whatever reason, and like you say, it’s almost a little bit disturbing that this movement hasn’t said what it meant to say and been received.

Yeah, and I think that’s part of it. These battles have to be fought over and over again. You know, you feel like things have moved on, and you realize that for large portions of society, there’s been nothing… [I] mean, I grew up in a kind of socialist country in Britain in the 60s and 70s. It wasn’t until Margaret Thatcher came in – which is an interesting gender issue, you know – that [there was] the first female prime minister of Great Britain; did absolutely nothing for women. Probably put women’s cause back twenty years [laughs]. And then moving to the states, it’s interesting as well.

I don’t know. I feel like you have to be really vigilant with all this stuff. There’s this whole movement right now of political correctness: “Aren’t political people boring? Why can’t we just be glib and ironic instead?” We can laugh at everything, everything’s funny… [I] just found a few years ago that I really admire people in the pro-choice community and the LGBT community, who’ve been just constantly having to chip away at these things. You know, I was involved in the anti-death-penalty movement, which is a huge issue for me in this country, coming from somewhere where there wasn’t a death penalty. It’s two steps forward, one step back, you know? The struggle is never really over. There [are] symbolic things, but, you have to keep revisiting these things.

Speaking of the US vs. the UK, speaking of history: punk kind of came along, said what it needed to say in that time, and we’re still kind of hanging on to it. There’s something there that still resonates with us, and this is also true of American country/roots music… I wanted to pick your brain about how roots, country, whatever label you want to put on it, how does it overlap with punk? How do you think these styles mingle for you? Do they?

Speaking of the US vs. the UK, speaking of history: punk kind of came along, said what it needed to say in that time, and we’re still kind of hanging on to it. There’s something there that still resonates with us, and this is also true of American country/roots music… I wanted to pick your brain about how roots, country, whatever label you want to put on it, how does it overlap with punk? How do you think these styles mingle for you? Do they?

They absolutely do. You know, we started off as a punk band, and it was just about making your own entertainment. We were like eighteen, nineteen years old. We didn’t have a huge grasp of the traditions of folk music, country music, anything like that. All these things dawned on us later. We were trying to make music where the purpose wasn’t fame and money; the focus was political and social conversation. And that’s what, I think, a lot of the best folk music, country music, blues, reggae, it’s functional music that people were making anyway. The commercial music industry, almost throughout history, going all the way back, it’s kind of a blip on the landscape. This idea of, like, selling a million records and blah, blah, blah. I see music as very operative and a communal thing.

Definitely what the similarities are between punk rock and country music specifically [are] like: these very simple forms, egalitarian, inclusive, easy to pick up an instrument and join in. And you know, the songs tried not to pander to escapist notions, but tried to deal with everyday life in a conversational sort of way. I never really liked the aspects of punk rock that were sort of lecturing, preaching, political stuff. We always try to steer away from that. For us, it was about… everything’s kind of like an exploration, kind of a conversation. Having discovered all the other music over the years, you find a lot of parallels between what we started out trying to do when we were kids, which still holds true. You know, there’s a thread that goes all the way back to those days, definitely with what The Mekons have been doing and with what I’ve been trying to do with other bands: to try and make something that exists outside the bounds or limits of just trying to make a few bucks [laughs].

Have you ever been to our part of the country before? What influence has, say, the Mississippi Delta had in your playing or your art? I notice a little bit of folk art touches that crop up.

I was down in Oxford a couple of years ago. I did an art show in a gallery just off the square, and I played at a sushi bar. That was pretty wild. I just played on my own, acoustically. I had a great time. I like Oxford. It’s kind of startling to me, a lot of the “southern” thing. It kind of freaks me out. I went to the Ole Miss campus and saw the statues of the first black guy who went – what’s his name?

James Meredith.

That’s right, James Meredith. And you know, it’s kind of like this ambiguous, weird piece of public art: this guy walking through a door, and it’s not in any way, shape or form explained with historical context, having what’s really going on in the picture. And then, the street has, like, these giant statues of Confederate soldiers paid for by the Daughters of the Confederacy, whoever they are. [laughs] Basically saying, “remember back when we had slavery?” I found it quite raw when I went there. I do realize quite how much these arguments are still alive, and how, again, there’s another victory in the ‘60s: James Meredith getting to Ole Miss, and then black people still fighting over and over again, still trying to get something resembling equality in this country. Women, as well.

You’ve got a guy running for president, the front runner of the Republican Party, who said if he was twenty years younger he’d be dating his daughter because she’s so hot [laughs]. That’s pretty f****d up.

Yeah, I think in the history books, Donald Trump is going to be a hard one to explain to my kids.

Somebody said to me the other day, it’s probably just because he says what he thinks; it’s what he thinks that’s the problem! [laughs] You know, he’s like a breath of foul air.

Well, you know, you’re stepping back into Mississippi during another controversy. I guess you’ve heard about the Mississippi state flag?

You know, you started the conversation talking about all these political things that just keep going and going. You can’t take anything for granted. The rich and the powerful are pretty f*****g tenacious.

That aside, you’re going to be playing on the lawn at Rowan Oak, is that right?

Yeah, we’ll be there for Thacker Mountain Radio. I actually did that show once before, when it was in the bookstore. I got to visit Faulkner’s house as well.

Are you a Faulkner fan?

Yeah, to be honest. I read Faulkner when I was quite young. It was a real insight into a totally different view of America than what I was getting watching F Troop and The Munsters. I was probably about eighteen or nineteen. I was reading, like, Graham Greene and people like that at the time…

[T]hat’s another thing that’s interesting about Oxford: the way people talk about Faulkner. Faulkner’s kind of like, he died last week or something, you know? I’m from Wales, and we have a similar relationship with Dylan Thomas, I think. You know, he’s kind of like “ours,” and it’s hard for me to tell how good he is. But for me, he’s really, really good. And if I was from the south… Well, i think Faulkner’s really good, but i’m from South Wales [laughs].

Since you are from Wales and then decided to come over here, very generally, what was the appeal of this quintessentially American style of music? What was it for you that made you say, “this is something that really resonates with me, this style of music is something I really want to pursue?”

I think that, for a time, when the first kind of wave of punk rock crashed against the rocks, we all felt a bit lost and didn’t quite know what we were doing. So we suddenly starting looking around and finding these new things, and there was something about classic ‘50s and ‘60s honky-tonk music that I thought was really strong. You know, I knew about Johnny Cash, I knew about Elvis and people like that. But I’d never heard this stuff, and I liked the way it was talking very directly to its audience. A lot of things were like parallels to what [The Mekons] didn’t really know we were trying to do, but we have been trying to do. And it was great to put that in a context. I also kind of fell in love with the cool civilian uniform. Getting to wear cowboy shirts… British people don’t have a cool uniform. Like, in Wales, you wear a rugby shirt or something like that. But definitely, we’ve swallowed the whole thing, The Mekons coming over to the States. You know, going to western wear shops. We wanted to feel the part.

So it was more of an aesthetic thing than it was necessarily a musical thing?

No, it was a mixture. I just would have felt like a bit of a wanker getting up and singing a blues song. I love reggae music, but I didn’t want to start putting on a fake Jamaican accent like Sting. We’ve incorporated blues and reggae and all sorts of music into what we do, but you know, I feel like at a bar like the Sundowners’ ranch or the Double-R Ranch in Chicago, I think it feels so weird getting up onstage and singing a Johnny Cash song. I didn’t feel like some kind of cultural imperialist or something. It felt alright. It’s strange.

Having said that, I sang a Jimmy Reed song at Rose’s, which is a great blues club in Chicago, the other night. That was great, as well. So i’m branching out [laughs]. I played with the Kinsey Report, have you heard of them?

No, I haven’t.

They’re a fantastic blues band in Chicago, and I jammed with them. They were like, “you should get up and sing with us, man!” So I did. And it was great!

You’ve been in Chicago how long?

23 years.

Can you put your finger on the pulse of Chicago art and music for me?

I think the thing, when I moved here… there was a lot of space here. It wasn’t quite as gentrified. A lot of artists were moving here because it was cheap to live, and there was a lot of structure that was useful, especially for musicians. Not that kind of L.A. or New York scene where people go to crawl their way over the bodies. Chicago was a place where you could come and do your own specific little thing, and be supported by journalists, radio. It’s changing all the time, but I’m in the middle of it so much, I’m the frog in the boiling water. I can’t tell how much it’s heating up.

I also briefly wanted to talk about your visual art. I was curious what some of your influences were.

I started off making little tribute pieces to country singers that I liked because I felt they were being abandoned. You know, I met [Johnny] Cash in the late ‘80s, and I did a painting of him for an album cover. And for me, it was weird to find out that his career was going down the toilet and he was really unhappy. I thought that was kind of impossible. “You’re Johnny Cash! You are country music!” and he said, “Well, I don’t get played on country radio, neither does George Jones, neither does Merle Haggard.” And these were all the guys I was listening to at the time, and I just did not compute. I think around the same time, they moved the Grand Ole Opry out to a shopping mall, and you know, it was just this kind of weird commodification of the things that I loved. So they kind of demolished country music that I liked, and abandoned it, and pushed it in a totally different direction, where [it] seemed to be fueled by this desire to be a big, giant, corporate thing. Nothing coming from the grassroots up, it’s all coming from the other way.

So it was more about preservation, then?

Really, I was just making pictures about all this music. I felt like the people deserved something. I started making all these little pictures of country singers and painting them almost as kind of like religious icons, with words like “neglect” and “doom” on them [laughs]. Cheerful guy.

Is that desire to preserve this bygone style something that –

I didn’t feel like it was a bygone style, I felt like the content and subject matter of original country music had absolutely been censored and erased, you know? I felt like what was white workingman’s blues music that told real stories of real life had been replaced by some fantasy, escapist music sponsored by the Republican Party and big corporations to make you nostalgic for an America which never f*****g ever existed anyway.

Is there something about the myth of Americana that appeals to you, or is it just kind of the subject matter of the individual songs?

Yeah, it’s the whole package, isn’t it? “Americana,” that’s a kind of a category of fairly recent invention, but this whole idea of America in the 20th century is fascinating, you know?

How so?

The country that gave us Hank Williams and Miles Davis is also the country that gave us Selma and Nagasaki. And all the movies. 20th-century America is a huge cultural explosion that dragged the rest of the world along. Everyone’s eyes were on America in the 20th century. In the 1980s, we hated it and we loved it. There was so much to discover. It was f*****g Ronald Reagan, leading the world to hell.

Do you still see a lot of that America today, or do you think it’s changed?

I live in the middle of it.

Frog in the boiling water?

Yeah, a little. Things disappear. American values are very weird. The stuff that inspired all this incredible, beautiful cultural glory is kind of evaporating. I don’t know. It’s like the death of an empire or something… I don’t know if there is a culture here at the moment that’s all that interesting. It’s probably elsewhere in the world. There’s always an underground, but I don’t know. There was great innovation right at the heart of the mainstream, because it was moving so fast that the money men couldn’t keep up with it. Now the money men have got the lid on, and it’s difficult. ![]()

–

Not enough Jon Langford? Check out this awesome link we found over at Rolling Stone:

Fear, Whiskey and Punk Rock: The Story Behind the Kick-Ass Mekons Doc[umentary]

–