In the first edition of this column (ie, “Rock Around the Clock”), I wrote about my earliest sense of feeling Southern. The trigger was hearing “Dixie” played on a juke box while spending the summer of ’54 as a guest of my cousin Helen Hawkins Weber and her husband Mack, near Fontana Dam in the Great Smokey Mountains of North Carolina.

I’ve long known that Helen had two brothers, Reynolds (my namesake*) and Russell. I hadn’t known, until recently, that she had had another brother.

Back around the time of my 64th birthday, I wrote a little about Reynolds and Russell here. For awhile they lived under the same roof with my dad and his two brothers (John and Billy) in Pine Bluff.

Dad once mentioned that Russell was always playful. So much so that my grandmother, a high school teacher of English and Civics, at times would order Russell to sit still with one of his schoolbooks for an hour. If Russell exclaimed, “But, Auntie, I’m not reading the book!”, my grandmother would respond that she hadn’t said he had to read it, but rather that he had to sit still with it.

Of Reynolds, dad just said he was always the serious one. I recently learned what I believe to be a part of the reason for this. The first step on the path of this discovery came when I joined Ancestry.com

Rather than looking to confirm family lore about my ancestors’ ethnic roots (the family lore turns out to be amazingly accurate; details for a later time), my primary purpose in sending a DNA sample to Ancestry was to look for living relatives. (Of course we’re all related; but nevertheless, more closely related to some people than to others.) I was very pleasantly surprised by the contacts I soon made — a few after a hiatus of decades, and another few for the first time ever.

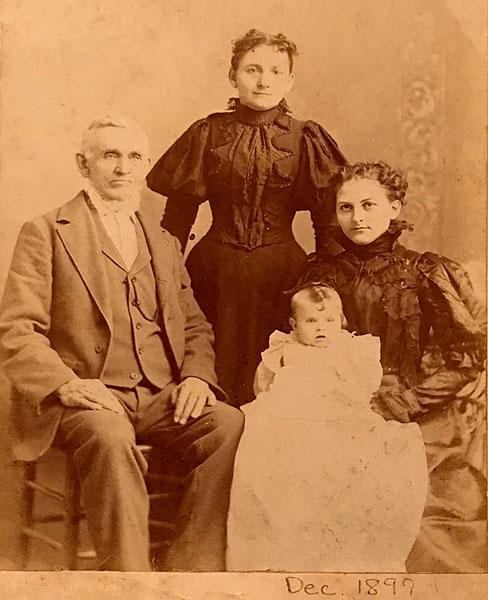

Among the first artifacts I came upon along The Southern Front† of my paternal ancestors is this photo dated “Dec. 1897”. Standing is my great grandmother, Mary (“Molly”) Reynolds Lynn (1857 – 1901) of Desoto Cty, Mississippi. Seated on the left is her father, George Alfred Reynolds (1823 – 1906) of Union City, Tennessee. Seated on the right is Molly’s daughter, my grandmother Russell’s sister May Lynn Hawkins (1877 – 1975), also of Union City, but later, as shall be seen, of Edna, Texas. ¶

I had no idea who the baby was on her lap, but I knew Reynolds was born 2 years later, and his siblings Helen and Russell were born after that.

Eventually, I learned that the baby’s name is Richard Lynn Hawkins, and that he died at age 12. I assumed he’d succumbed to an infectious disease, a cause of death much more prevalent among the young back then than now. It turns out the cause of his death was more complicated. Recently there came into my possession a copy of a letter written more than 30 years ago by cousin Helen (now no longer with us), explaining what happened [slight editing]:

Richard Lynn Hawkins 1897–1910

It occurs to me that I am the only one left who remembers Lynn, that gallant, brave, and brilliant boy, not quite thirteen years of age—who gave his life for me. The awful impact of it only occasionally hits me. I guess I couldn’t stand it if it were constant.

I was seven, Reynolds nine. We had been in Texas a couple of years, part of the time out on the ranch—the Apple T, whose cattle brand was an apple with a T imposed upon it. For us, as children, that was very heaven. I can shut my eyes now and see Reynolds flying across the open plains on his horse, “Headlight”, a beautiful brown Mustang pony. (Reynolds was riding him by age seven—a horseman.)

My memory of Lynn at that time was as a protector and big brother to Reynolds and me. Every day he read to us—the Joel Chandler Harris Uncle Remus stories, Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur with Sir Galahad and the Round Table. He read every word of the Youth’s Companion to us. I read the other day that the “Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag” appeared originally in its pages.

He read to us all about Robinson Crusoe and his man Friday, and Dickens’ Christmas Carol, and Bible stories too. All of this when we must have been very young. But it was from him that those beautiful classics came to me.

That July morning of 1910 was very hot. Mother had called to Lynn to take off his jacket. (Later she regretted it, because it might have been a layer of protection.)

The girl who was ironing in the servants’ house called to Lynn to come and fill the gasoline stove for her irons. I was right at his heels, as I usually was, and was by his side when he poured the gasoline into the hot little tank. The stove exploded.

“Run, Little Sister! Run!” he yelled. I was frozen in my tracks. “Jump out the window,” he urged. But I was terrified. He saw nothing to do but lift the flaming stove and run for the horse lot. By that time our screams had alerted Father and Mother, who came running. Father grabbed Lynn and threw him into the horse trough.

He was burned over his entire body. “Why, oh why,” Mother asked frantically, “didn’t you just let the place burn?”

“Little Sister was there,” he replied.

Neighbors, Dr. Radkey, the whole little town of Edna did all they knew to do. Three days—and he died. The shining hope of his loving family.

That summer, he was reading Caesar’s Commentaries. Texas at the time had only ten grades. Lynn, who would be thirteen, was to enter his junior year, with graduation at fourteen. An excellent student, the only one of us who inherited Father’s height. They had dreams of sending him to Harvard—my mother’s dreams had a way of materializing, so he doubtless would have made it.

The day he was buried, a few days before his thirteenth birthday, Reynolds wrapped his arms about me and whispered through his sobs, “Don’t cry, Little Sister, I will take care of you.” And he did—throughout the years—many, many times.

My beautiful, brave, and loyal brothers. The third brother was born in July 1911—Russell Lynn. He always said he was a replacement. He really was. Father would get astride old Prince, Russell at scarcely two, tied to the saddle on my pony, “Sport,” following him all over the place. They made a wonderful picture.

We were about settling down to a normal, happy family life when tragedy struck again. Father died on December 23, 1914, and was buried Christmas Eve.

Mother was thirty-seven. We children were fifteen, twelve, and three. As I look back now, I realize how strong she was. Indeed, she was magnificent. But I’ll write about that later.

This terrible event that happened when Reynolds was only nine, and the family responsibilities that followed, especially after age 15 when his father died, might be a large part of why Reynolds was so serious.

* My real name is Reynolds William Joseph Russell. Thus, “Billy Joe Russell” is much closer to the underlying reality than “Gaetano Catelli”, a name I used to counter NYC bias against my Southern-sounding real name (not entirely successfully; details to come) Much later, I learned that my mother’s maternal grandfather had Gaetano as his first name .

† The Southern Front is the title of a book of essays by an eminent historian of the South, Eugene D. Genovese, who was born and raised a Sicilian-American Catholic in Brooklyn, NY; joined the Communist Party at age 15; later in life evolved into a Southern conservative(!); and returned to Catholicism in his final years. He will be quoted from time to time in future columns.

¶ Names, dates, and birthplaces are per archives of the Daughters of the American Revolution, which I hadn’t yet accessed when I wrote the “birthday” piece about my namesake, Reynolds Hawkins and a few other relatives. Some emendations of the piece are in order:

Hannah was indeed the name of Reynolds’s wife — but not the name of the sister of his mother (May) and my grandmother (Jessie). The third sister was, instead, Grace.

It was according to notes that I made when my father had only weeks to live that I recorded (perhaps the mistake was mine, not his) that the mother of my grandmother Jessie and her sisters was Mary Elizabeth Lynn. In fact, their mother was Mary Reynolds Lynn, whose nickname was “Molly” to distinguish her from her mother, Mary Elizabeth Reynolds.

Last, but not least, Reynolds Hawkins was, as noted, born in 1899. So, contrary to my dad’s recollection, the unplanned baby sitting on Molly’s lap in the photo dated 1897 was the (reported) cause of her leaving college, not Reynolds.