It was love at first listening when, at age 6, I heard the words “In Dixie’s land I’ll take my stand to live and die in Dixie!” The timeframe was the summer of ’54. The place was Fontana Village in North Carolina’s Great Smokey Mountains. My cousin Helen Hawkins Weber had invited me to spend the summer with her; her two daughters, Elizabeth and Gracie; and her husband, Mac(beth), who was working at the resort.

I’m pleasantly surprised that the resort’s website still has a few photos from that era, including a shot of their rec room. Just to the left of center can be seen the jukebox on which I first heard the song “Dixie”. I knew at once that the words “I’ll take my stand to live and die in Dixie!” were directed to me. (But I didn’t know that it would be another 56 years before Grace would lead me home.)

The title of this column also alludes to the book I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition by Twelve Southerners (as the authors of this collection of 12 essays style themselves). In the song, “stand” is a metaphor for son or daughter (as it’s been explained to me—as in a corn stalk standing in a field). But the book’s authors mean “stand” in the sense of their Agrarian stand on political and social issues.

As with Capitalism and Communism (and Judaism and Christianity), there’s no single definition of Agrarianism. With apologies for oversimplification, a useful way of looking at Capitalism is that it was originally the application of industrialism to free trade, and now also brings information technology to the mix. Free trade, in turn, is the idea that if I buy a can of Diet Coke for a dollar from a local store, I’m better off because I wanted the Diet Coke more than I wanted that particular dollar, and the store is better off for the converse reason. In other words, win-win.

As Capitalism is the ultimate form of free trade, Communism is the ultimate form of Marxism. For now, I’ll just say that Marxism as currently practiced is the belief that all inequality derives from social injustice, and only social injustice. Further, that any means necessary are justified in the cause of eliminating that inequality. If circumstances permit, I’ll have much to say in the future about Capitalism and Marxism as they apply to contemporary America in general and Southern Agrarianism in particular.

Note that both Capitalism and Marxism are godless—everything about them operates according to mechanical laws. (The spectacular predictive success of Newton’s physics strongly influenced both.) In my reading, Agrarianism asserts, by contrast, the primacy of traditional values of Faith, traditional values of Family, and traditional values of Patriotism, ie, loyalty to the soil you were born and raised on.

“Dixie” isn’t the only song I remember coming from that jukebox. There’s another: “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and his Comets. It had been released only a few months before. It’s widely recognized as the first rock ’n roll tune to reach the general public (ie, the White majority).

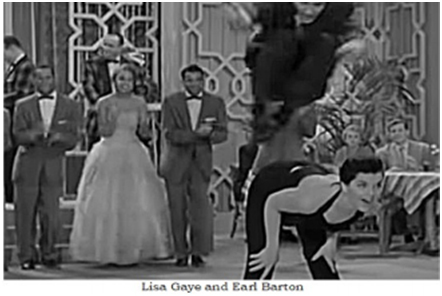

Compare and contrast that performance with the “Jumpin’ Jive” segment from the movie “Stormy Weather” made 11 years earlier. Surely Cab Calloway and his orchestra out-jived the Comets; and the Nicholas Brothers out-jumped the White couple. (Are the two men standing in the background in black face?)

My personal feeling about the “Rock” video is: Wow! That looks like fun! Whereas my feeling about the “Jumpin’ Jive” clip is: Goodness Gracious, great balls of fire — that’s impossible!!!

I think a reasonable person could assert that Bill Haley and his Comets had engaged in cultural appropriation (from many Black predecessor-performers). That their status as “pioneers” are analogous to claims that Europeans “discovered” the Americas (though people had already been here for some 15 millennia). That, as such, they have greatly benefited from White privilege (notwithstanding that they worked very hard to get where they got). It could even be said that the System itself tilts in favor of the White majority (as would likely be the case with any majority tribe anywhere).

But, beyond academic debate, the practical question is: What is to be done? Aye, there’s the rub. Because, whatever is done (or, not done), some will benefit more, or be harmed less, than others. I’m tipping my hand a bit by predicting that, if past be prelude, those who will benefit less, or lose more, will not be part of the pool of talent from which The New York Times and NPR (to name just two examples) draw their opinionators.

I hope to have the opportunity in future editions to explore these and other issues from a candidly Southern-partisan perspective that nonetheless seeks to be sensitive to more progressive sensibilities.

Oh, before I go, I need to mention a mystery that’s been plaguing me while writing this piece. Away from Fontana Village’s rec room, during mealtime at cousin Helen’s home, aside from becoming acquainted with Spam (about which I remain agnostic), I was introduced to saying Grace before eating. (It was not practiced in my parents’ home because, as an old ditty has it, Me father, he was Orange, and me mother, she was Green {in the denominational sense}.)

For related reasons, it was in Helen and Mac’s home that I was also introduced to spiritual music. There’s only one song I clearly remember hearing there: “The Bible Tells Me So”, if not in the voice of Dale Evans (who composed the song), then a voice remarkably similar.

I have carefully reconstructed the timeline (based upon other events the date of which I am certain) that places me in Fontana Village in the summer of 1954. Consistent with that placement, Wikipedia confirms “Rock Around the Clock” had been released that spring. And yet, according to the omniscient Internet, “The Bible Tells Me So” was not released until the late summer and early fall of 1955—in both cases by a male vocalist. Dale’s own recording didn’t come out until 1960.

Perhaps a more knowledgeable reader could resolve the puzzle for me. Or, maybe my memory has played a trick on me all these years.

Either way: Happy trails, until we meet again.