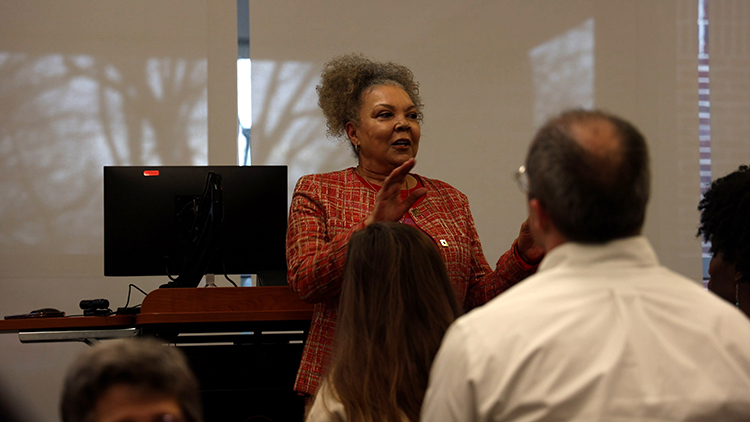

Judy Meredith, documentarian and retired professor of mass communications, discusses her film 'The Mystic, The Man: Who is James Meredith?' at a Feb. 16 screening in the Gertrude C. Ford Ole Miss Student Union at the University of Mississippi. Photo by Sam McGlone/University Marketing and Communications

Her documentary about husband James Meredith shown earlier in day

Recalling several African American firsts as if they happened only yesterday, Judy Meredith connected them to husband James Meredith‘s journey to become the first African American student at the University of Mississippi.

Before an almost standing-room-only crowd, Judy Meredith delivered the Black History Month keynote address Thursday February 16, 2023 at the university. Hundreds of UM students, faculty and staff, and local citizens filled the Gertrude C. Ford Ole Miss Student Union Ballroom to hear her perspectives on lessons to be gleaned from history.

“Knowledge of our history is important and imperative to learn for a number of reasons,” Meredith said. “It is especially important to learn about people, their cultures and their history, and about our own.

“History attaches us to a long umbilical cord, and if we choose to, we can use this connection to travel all the way back, so far back through time. Centuries across the earth and sea to arrive at this one special place called Africa.

“And as we take in the magnitude of it all, we realize that we all are an essential part of God’s plan.”

Meredith continued by quoting Pan-Africanism activist-journalist Marcus Garvey.

“‘A people without knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots,'” she said. “I say history can also help us understand the signs of imminent danger and give us answers to problems so we don’t have to reinvent the wheel.”

Meredith compared the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol to the events surrounding the 1962 integration of Ole Miss. Meredith thanked and praised her husband for making it possible for thousands of others to be able to choose whatever colleges or universities they wish to attend.

The speaker related “blasts from the past,” citing African American figures such as Katherine Johnson, a mathematician who helped NASA win the race to the moon; abolitionist Sojourner Truth; Shirley Chisholm, both the first African American congresswoman and female presidential candidate; musicians Nina Simone and Big Mama Thornton; Claudette Colvin, a pre-Rosa Parks bus rider who championed desegregation of public transportation; Mary Fields, the first African American postal worker; and the Rev. Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

She ended her message with an appeal for individuals to record their own family histories for future generations.

“Let us strive to walk down the path of equality,” Meredith said. “Living together happily is not the impossible dream. And that, my friends, is my blast from the past.”

As part of the keynote program, Phillis George, chair and professor of higher education, presented the annual “Lift Every Voice Award” to Anne Cafer, professor of sociology and director of the Center for Population Studies.

Before she took the stage Thursday, Judy Meredith stood before a crowd of more than 70 in another room of the Student Union for the first public screening of the documentary she produced, “The Mystic, The Man: Who is James Meredith?”

The documentary, a story of hope through adversity, features footage of her husband in conversation with family around the dinner table, on the Ole Miss campus during the 1962 riots and on the scene where he was shot in 1966 on the second day of his “March Against Fear,” a demonstration intended to highlight racial inequality in Mississippi.

“Thank you, wife – I guess that’s what I should call you when we’re in public,” James Meredith said with a smile after the screening. “I have to say, I think I got a better understanding about who James Meredith is today than I’ve ever had.”

Among the crowd were family and longtime friends of the Merediths, students, university officials and members of the documentary’s cast.

Donna Judd traveled from California to attend the screening and keynote event. Judd, who was a freshman during the 1962 riots at Ole Miss, kept a diary of her college years, including notes about the riot and its aftermath. Judy Meredith asked Judd to be part of the documentary after the two reconnected.

“My mother had given me a diary about a year before I went to college,” Judd said. “By the time I got finished writing about the riot, I had to add in index cards because I’d run out of paper.”

She approached the Merediths after the screening and presented the small, tattered diary she’d held onto for 60 years, still stuffed full of yellowed index cards. She asked James Meredith to sign the front page.

Pam Fingers, who first met Judy Meredith when they were 13 years old, said she and Judy grew up together, going to the same church and schools in Gary, Indiana. The two traveled together to Lincoln University in Missouri and have remained best friends for all their lives.

After the showing, Fingers held Meredith’s hand in a crowd of milling and applauding people.

“I’m trying to hold myself together,” Fingers said, putting a hand to her face. “I’m just so proud of you.”

By Edwin B. Smith and Clara Turnage