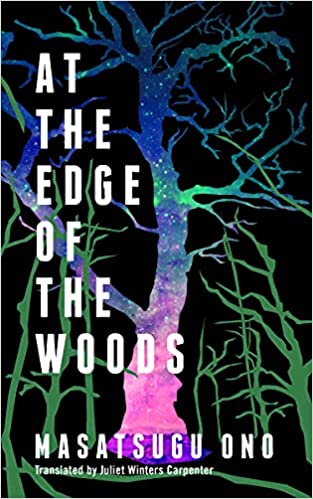

Two Lines Press ($16.95); Available April 12; preorder at Square Books

Masatsugu Ono’s latest novel, At the Edge of the Woods, is an unsettling domestic odyssey about the fear and uncertainty abounding in the mundane. A father, mother, and young boy live in a house deep in the woods. There are four chapters, each titled after their focus: “A Breast,” “The Old Leather Bag,” “The Dozing Gnarl,” and “The Cake Shop in the Woods.” In the first story, the mother leaves the father and son for the evening at home. The son has previously “begged his mother for a grandmother”:

“You already have a grandmother and grandfather,” I said. “Two of each, in fact!

You can have your pick.”

“Nooo,” he whined, near tears. “I want a grandma that’s all mine!”

What begins a relatable, slice-of-life episode ranges into the darkly mythic when the son goes to play in the woods and comes back with a mostly naked elderly woman, his very own “grandmother.” Here the story becomes a masterwork in suspense and tension derived out of the minutest interactions. The fairytale underpinnings elevate the warped nature of the plot. Not to spoil anything, but the ending of the “A Breast” section is disquieting in that most perfect way of classics by Poe and Hitchcock.

Ambiguity and anonymity also help to create suspense out of seemingly nowhere. No one is ever properly named, and the geographic setting of the book is totally unknown. So, on top of the layers of the everyday and the fable, there is an atmosphere of unreality. Ono shows a wide dexterity in tone, as well; some passages choose to underscore neutral, or even light-hearted, qualities, while others highlight mundanity. The copy on the back of the book claims it is “an allegory for societal alienation and climate catastrophe,” which is certainly a valid interpretation. While I didn’t come to that idea naturally in my reading, the human world and the natural in At the Edge of the World are certainly at odds; it appears that Ono’s characters cannot make sense in the context of Nature. However, the true pleasure of this book isn’t its message, but its method. Ono writes understated, almost minimalist stories that compel in a way that defies understanding. If you sometimes don’t feel quite right where you are, this novel will suck you in.