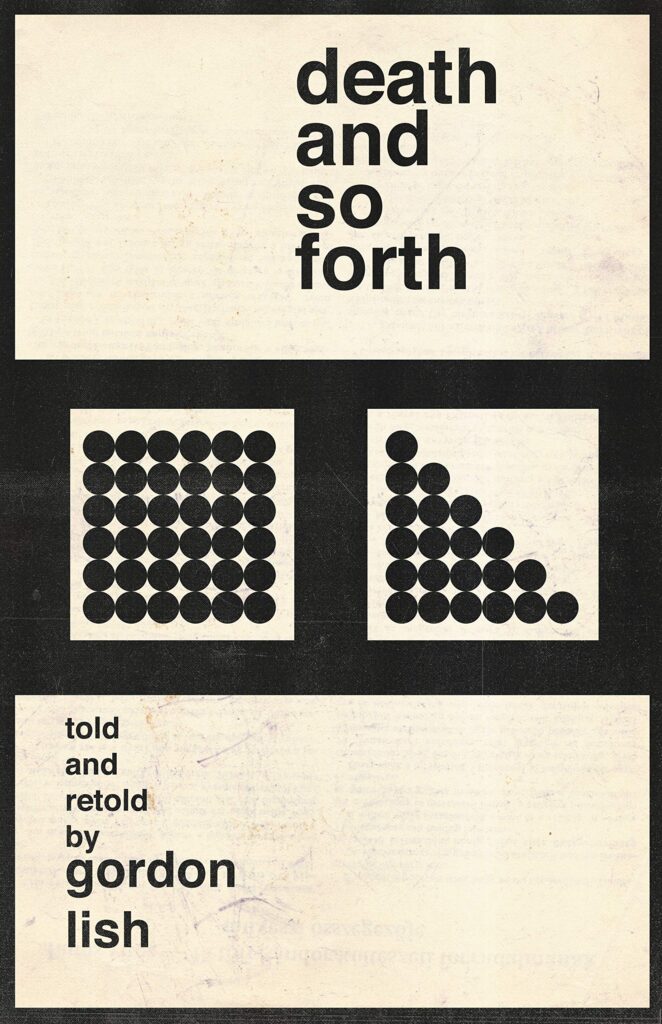

Death and So Forth

by Gordon Lish

Dzanc Books ($24.95)

Available at Square Books

click here to order

Longtime former editor at Esquire and Knopf, “Captain Fiction” Gordon Lish, hardly needs an introduction in most literary agoras, so I’ll keep this one short. He has championed an impressive list of writers, including Don DeLillo, Cynthia Ozick, Joy Williams, and Mississippi’s own Richard Ford and Barry Hannah. His severe edits of Raymond Carver’s short stories are as legendary as they are controversial. He taught creative writing at Yale, Columbia, and NYU for many years, influencing writers such as Ben Marcus, Sam Lipsyte, Diane Williams, and Garielle Lutz. His son, Atticus Lish, is a widely acclaimed novelist whose third book, The War for Gloria, came out this past year to enthusiastic praise. And throughout his career as an editor and teacher, Gordon Lish has been steadily releasing his own novels and short stories. Death and So Forth (2021) is his latest collection.

To say that this book, if you choose to read it, will be unlike anything else you will read this year, is an intractable oath, a sober prophecy, and an easy bet. Lish’s affinity for experimentation and distaste for the commonplace are clear in every story, and even outside the bounds of the text. On the latter: the front cover has written after the title “told and retold by gordon lish.” The inside flaps, instead of the usual sales copy and author photo, have a short dialogue: “Hold it a sec! Where do you suppose this ‘so forth’ is coming from?” “There is no so forth. Nor neither is there any ‘and’ either.” To replace blurbs, the back has a cryptic and self-aware short story. Even the introduction is refashioned into a monologue. The acknowledgments page looks more like a poem, and thanks a few people for “invaluable considerations involving the formation and, accordingly, deformation of holes, hollows, cavities, hosts, circumflictions, and circumflexes.” The author bio is likewise a story in verse:

At the gravesite

of a friend,

a man is asked

by the rabbi presiding

to say a few words

regarding the deceased.

The man says,

“His brother was worse.”

Now onto the meat of the text: Lish has an uncanny ability to move a story along through the sheer power of voice, while the typical conventionalities of the form, so comforting to readers, are abandoned for newer lands. Several stories, like “Naugahyde” and “Speakage,” work like dramatic dialogues. “Does This Mean Anythugng?” tries to wrestle meaning through typos, humorously and recursively. But when the experimentation gets too much, Lish knows how to go for the heart, and thereby center the reader. “Grace” is a tragic piece of autofiction, focused on the author’s feelings being stood up by two writers for dinner, while his wife is on her deathbed. There are also eulogies for Harold Bloom, Denis Johnson, and others.

Their perspective and diction make these stories unique, truly sui generis (Lish has few obvious literary ancestors you can anchor him to, and he freely admits those that he has, namely Beckett), but their subjects are seen to be those that have haunted our language forever: personal history, work, love, death, and so forth, etc.