GEDSC DIGITAL CAMERA

[Editor’s note: This is an extended version of the interview found in TLV #238 with legendary performer and activist Amy Ray. Enjoy!]

–

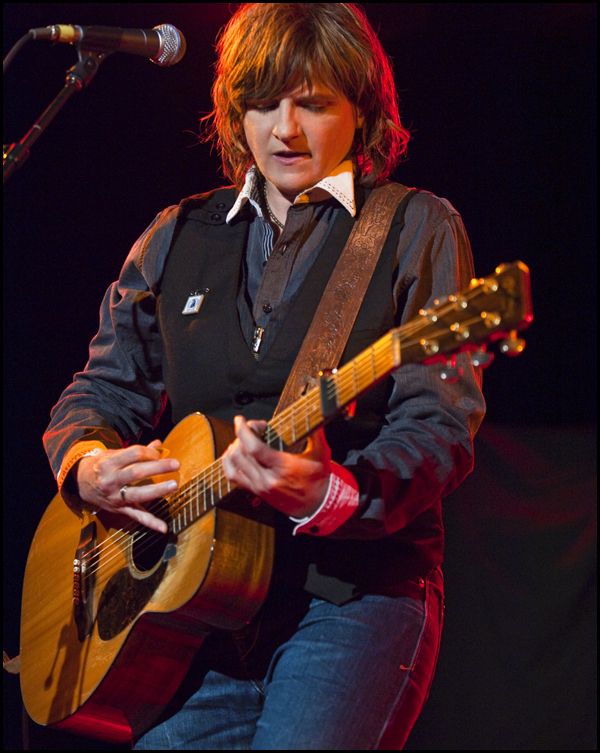

Amy Ray is a singer-songwriter and record producer who came to prominence as one-half of The Indigo Girls. She also founded the not-for-profit Daemon Records label in her hometown of Decatur, Georgia. She has a noted track record of support for women’s and queer rights movements, indigenous peoples, and environmental concerns.

How did you get involved with Sarahfest?

Initially, I came into an event with the Thacker Mountain Radio show with T. Cooper, the writer, and then I was talking to Theresa Starkey. She was like, “let me do this thing,” because we were waxing poetically about all the musicians we both loved, and it was like, Kelly Hogan and Jon Langford and Neko Case. She was like, “I’m gonna put this festival together, do you want to come do it?” And I said, “if I can get the day off, I’ll totally do it!” Mostly because I think that the [Isom] Center is such a great place. You know, it’s hard to keep a community space at a college in the south – I know because I’m southern – open and thriving in [that] subject matter. I think Oxford’s a pretty cool town in that way, and I loved being there just generally speaking. So of course, I wanted to come do it. I love Kelly, I’ve known her for a long time, and I’m a huge fan of Jon Langford, so for me it’s just a great opportunity to actually just go see everybody else.

Initially, I came into an event with the Thacker Mountain Radio show with T. Cooper, the writer, and then I was talking to Theresa Starkey. She was like, “let me do this thing,” because we were waxing poetically about all the musicians we both loved, and it was like, Kelly Hogan and Jon Langford and Neko Case. She was like, “I’m gonna put this festival together, do you want to come do it?” And I said, “if I can get the day off, I’ll totally do it!” Mostly because I think that the [Isom] Center is such a great place. You know, it’s hard to keep a community space at a college in the south – I know because I’m southern – open and thriving in [that] subject matter. I think Oxford’s a pretty cool town in that way, and I loved being there just generally speaking. So of course, I wanted to come do it. I love Kelly, I’ve known her for a long time, and I’m a huge fan of Jon Langford, so for me it’s just a great opportunity to actually just go see everybody else.

You mentioned the fact that you’re obviously southern. I wanted to get your thoughts on that southern identity, and how it informs you socially, mostly, but also creatively.

I’ve played everything from folk, to punk rock, and then solo I did a country record, it’s my last record. A lot of mountain influences in it. And those are just all the different kinds of music that I like. I find that, definitely, the south informs your images and the way you write, and kind of the way you move in life. It’s not as competitive; it’s more community-based, in some ways. When you find your people, and people that want to work for good, and really feel a kinship to the south – but not the negative things of the south – you find each other and you sort of influence each other, and take inspiration from that. It’s just like a different vibe, I think, than other places. I’m not sure how to describe it, but there’s more of a spiritual attachment I think. Whether you’re religious in a Christian way, or Jewish, or whatever you are, there’s a spirituality that runs through everything. That’s part of the civil rights movement, and part of what you do, and there’s a sacredness to everything.

Not that everything has to be so reverent. It can still be funny, because things can be so absurd, but it’s not as secular and dry and intellectual. That’s what I love about southern art, generally, is that there’s a sense of humor in all the heaviness of it. There’s still a sense of humor, and an absurdity that I find really appealing. I guess for me, because I’m queer and pretty left-wing, I’ve always had a lot of things to rub up against being southern – and in a way, it’s what I’m used to, and what I feel comfortable with. As opposed to being in a bubble and everybody agreeing with exactly my perspective. I actually like the idea of having this incredible space in the middle of a very conservative area that informs that space in some ways, too, because you learn to dialogue with people that feel so differently from you, and you learn to build bridges. So, you might work with people that have different political views, but you’re making a farmer’s market. Or, you’re creating a Habitat For Humanity space, or whatever it is. In the south, in order to build anything, you have to have people that have different perspectives from yourself.

I like that. I like the fact that you don’t just have this vacuum of liberalness with nothing that informs it, and nothing that makes you understand the context that you’re working on your issues in, you know? It’s amazing for one area to have such a rich heritage culturally, anyway, and I know the university has a lot to do with that. It’s always interesting to see the dynamic between a rural area and a university, and the small town, and how all the different populations mix together. I find Oxford to be fascinating in that way. I live in north Georgia, actually, and it’s a very rural area, too. There’s actually a college in the town.

Sarahfest, and the Isom Center more generally, are looking to celebrate the achievement of women in art, and they also deal very heavily in the LGBTQ community. What’s the state of women today in popular music, and particularly LGBTQ concerns? Do you think it is different? Is it a question of the audience having changed over the years? Or is it just not a factor at all?

I think it’s a factor. It’s a big factor. I think the audience tends to change faster than the industry does, in terms of their willingness to be open, and more diverse, and accepting. Also, just generally, listening to different kinds of music. Not being so closed-minded. I think a lot of marketing people in music… for a long time, there was always research, research, research about what stations should play, and it was very segregated at some point in the mid-90s when everything changed with the Telecommunications Act. But, I think what you see with the internet and younger generations coming up is that there’s so much cross-pollination. And that also breaks down barriers with racism and homophobia and sexism, because I think when the music is passing through these non-gatekeepers, if you will, it’s not filtered the same way. I’m not talking about Sirius/XM-type stuff. I just mean, like, the way people get their music through YouTube, word of mouth, whatever. There’s not the same packaging and sort of image associated with it. So, often times, people are just listening to things because they like them, which is kind of cool.

I think it’s a factor. It’s a big factor. I think the audience tends to change faster than the industry does, in terms of their willingness to be open, and more diverse, and accepting. Also, just generally, listening to different kinds of music. Not being so closed-minded. I think a lot of marketing people in music… for a long time, there was always research, research, research about what stations should play, and it was very segregated at some point in the mid-90s when everything changed with the Telecommunications Act. But, I think what you see with the internet and younger generations coming up is that there’s so much cross-pollination. And that also breaks down barriers with racism and homophobia and sexism, because I think when the music is passing through these non-gatekeepers, if you will, it’s not filtered the same way. I’m not talking about Sirius/XM-type stuff. I just mean, like, the way people get their music through YouTube, word of mouth, whatever. There’s not the same packaging and sort of image associated with it. So, often times, people are just listening to things because they like them, which is kind of cool.

But I think women, generally, have a long way to go still in the music industry, even though I think it is better than it was. There [are] more women, and more women in technical positions, too; and the youngest generations that are in their teens now, like my nieces and nephews, they’re just totally different in the way they see things. So that’ll help. But I think that there are still a lot of dinosaurs in the business, and they need to die off, basically. That probably includes me! [laughs] “Make way!” You know?

Oh, I don’t know about that.

You know, if you’re in an airport, and there’s a display about rock n’ roll in that city, it’s all men. That kind of thing is still pretty much the norm, and it takes such a huge shift to change that, because it has to do with how women are archived, and how they’re written [about], and how the media covers them, and whether they’re put into books and put into greatest hits collections from certain time periods. Whether they’re seen as influential in the history of music. And that takes so long. So, when you look at it from that perspective, we’ve got a long way to go.

But from the perspective of, like, infrastructure, and the ability to access things, it’s so much better than it used to be, because we don’t have to wait for somebody to tell us we’re okay and we can do this. We can do it ourselves. That was happening when Emily [Saliers of The Indigo Girls] and I were coming up. The DIY movement of the punk scene, especially, inspired us a lot. Even though we were playing folk music, we took all of our cues from the punk movement, you know? What they were doing, how they were achieving what they were doing, and I think that still rings true for girls, for women, for the trans movement, for the Homocore movement, the Queercore music movement. If you’re like, “this is never gonna be in the mainstream, and it’s never gonna be this or that,” you just go for it, and sometimes you break through.

Hurray for the Riff Raff is a great example of a band. They were at the Americana Music Awards. That never would have happened ten years ago. It’s a trans-oriented group. That is showing you that something’s changing, but the reason it’s changing is in spite of the business and the powers-that-be, because of the people that took it upon themselves to do their own thing, and the audiences responded. I think, culturally, we don’t give [people] enough credit for being more open and willing to accept new things. Nowadays, culture’s so easy to access that audiences are showing that they can respond.

I mean, that’s how I feel. It used to be, probably fifteen years ago, there might be a lot of people who were not gay in our audience, and a lot of families, and a lot of straight men, for instance. They might be out there, but no one would acknowledge that our audience had that element. It was always like, “they have a gay audience, they have a gay audience.” And half of that was because people that came to see us that weren’t gay were sometimes afraid to say that they liked us [laughs]. I mean, it’s true! There’s a generation of guys who are all in their thirties who are like, “oh yeah, The Indigo Girls, I was brought up on The Indigo Girls,” things like that. I’m surprised, because I still have so much of my own homophobia. I’m like, “wow, you’re Justin Vernon! How could you like The Indigo Girls? We’re so stupid and uncool!” But there are a lot of guys in that age group who just didn’t have the same barriers. The younger it gets, the better it gets. And I’m not dissing people who are my age and older, I’m just saying, people in their late 40s or 50s, we just went through a different experience, the way demographics work, and marketing, and barriers and stuff. Some of us even had to fight our own self-hatred, you know? It’s so neat to see people who are so much freer than that.

I feel positive about it, but I’m aware that in the mainstream, and in the biggest sort of archival sense of the word, it’s still a struggle. So it’s really important to have community space that’s geared around gender and sexuality, and also geared around race, and class, and mass incarceration; you know, all these subjects that we talk about where they seem like different subjects, but they’re all linked together by a common core. I think people that are activists get that now, which is cool, too. And so, community helps community, and as soon as you get a leg up, you help somebody who needs to get a leg up. These spaces – I think it’s especially true with queer-centered activism – where all of a sudden, queers turned around and said, “wait a minute, we need to help with this immigration issue, too, and we need to help with racism, and we need to help with social justice issues, generally; we can’t just work on queer issues.” Because what is a queer issue if it doesn’t encompass all those other things?

You’ve been very active and outspoken in arenas outside of music, and I’m wondering about your thoughts on music – and entertainment more generally – as a means to affect social change. I can see arguments that it’s more effective than some sorts of activism, because it’s more visible, perhaps, but I can also see arguments that it’s more removed.

I mean, I guess it depends on the issue and how the artist is approaching their activism. I think in the civil rights era, the music was something that brought the movement together, because they were community songs that people sang together. Artists weren’t doing it from an egocentric place. When Pete Seeger got out there and played something – or whoever – it was from a perspective of really bringing people together, and really, that was the focus of it. So, music was a tool to lift your spirit, and get people really united and bonded together for something so that they had more strength to take the march.

I think Rage Against the Machine was actually really good at that, and Tom Morello himself, when he went and did some of his stuff with unions in the labor movement and really understood that approach. And I think Zack [de la Rocha] was writing about really important things early on, and people were listening and learning about the Zapatistas, or things that weren’t getting much exposure. So, the way they did it was very smart, and the lyrics were smart, and they were getting through to a bunch of people who might not have known about that anyway, because the media wasn’t talking about it that much. So it depends. You know, if an artist is just toying around and they have a couple tables in the lobby to do something or other, but they’re not really focusing on it or talking about it, or really investing much into it, it doesn’t do anything, really. So it’s just like any kind of activism; you have to have major intention behind it, and I don’t think [music] solely on its own can change things. I think there has to be intention, and the context has to be right, and everything.

I don’t think it’s the only reason to play music, either. Obviously, I think a good dance song is a good dance song. Sometimes, that’s the best form of rebellion, is going to hear a band and being with people who may not look like you, and singing along and dancing with them and getting to know each other. Live music, for instance, is such a visceral experience that we maybe don’t experience as much as we should anymore, a lot of us, because we don’t get out, or younger people do different things, or whatever is happening. So I think, as a vehicle for social change, it just depends. But I do know this: activists that I respect that have done great work in the native communities, or in the African-American communities – art and song is always part of what they’re doing. Always. It’s not the reason for what they’re doing, you know? It’s just the thing that makes it more fun, or gives them strength when they feel weak. If it’s a native group working on an issue around nuclear waste, or a coal-fired power plant, they’re gonna have a drum circle, or they’re gonna have dancing, or they’re gonna have an art presentation, because they need to. There’s gotta be something that’s not in the head, that comes from a different place. I think it’s the fabric of it, but it can’t be effective unless you know what you’re doing, you’re coming from a community point, and you’re voicing the community, not just your own ego. ![]()

–