GEDSC DIGITAL CAMERA

First of all, this story is 100% true. My Daddy died on a Wednesday—the night before Thanksgiving. This isn’t about that, though. Not really. His funeral was held that Friday, and this is the saga of the 24-or-so hours after his graveside service, after I threw a shovelful of dirt into his grave and walked out of the cemetery. This is the story of a Friday night in my hometown, a “Massive Night” (as The Hold Steady might call it).

After the service, I insisted on a few reasonable hours of solitude, doing whatever the f**k I wanted—mostly driving on “my” backroads—one of my favorite activities. I didn’t have a car at the time, but for awhile before his passing my daddy was unable to drive, leaving an extra Chevy S-10 truck in my mom’s driveway. When I visited, she let me drive it to get to-and-fro in the Delta.

After the service, I insisted on a few reasonable hours of solitude, doing whatever the f**k I wanted—mostly driving on “my” backroads—one of my favorite activities. I didn’t have a car at the time, but for awhile before his passing my daddy was unable to drive, leaving an extra Chevy S-10 truck in my mom’s driveway. When I visited, she let me drive it to get to-and-fro in the Delta.

When I felt like seeing people again, I realized I hadn’t heard from an old friend in a few years (we’ll call him Jonah: Vonnegut said “Why not?” in the first lines of Cat’s Cradle). Jonah lived in Arkansas but I figured he might be visiting his folks since it was Thanksgiving weekend. I drove up to the huge old house his parents call home and knocked. His dad opened the door, surprised, and led me to the den where we found Jonah wandering around the room reading a book. We hugged, and after he conveyed his sympathy we made a food and booze date for seven o’clock.

All I really remember about dinner is that the Mexican food was lacking, compared to Oxford’s options. After queso and a tequila shot (because, why not?) we headed to the liquor store. It’s owned and run by my 3rd-and-4th grade schoolteacher—I always get a kick out of buying whiskey and wine from her. I bought a large bottle of Martini & Rossi Asti Spumante and…after that it gets fuzzy. Some kind of wine, though—a tradition for our location. And Jonah made a purchase.

I drove around for a few minutes, in a seemingly aimless manner. I’m a lot like Douglas Adams’ character Dirk Gently in that way; sometimes I utilize his “Zen method of navigation,” and I just follow a car that looks like it knows where it’s going. Mostly I just enjoy driving. But our destination that Friday night was inevitable. Where could we go where nobody would find or bother us?

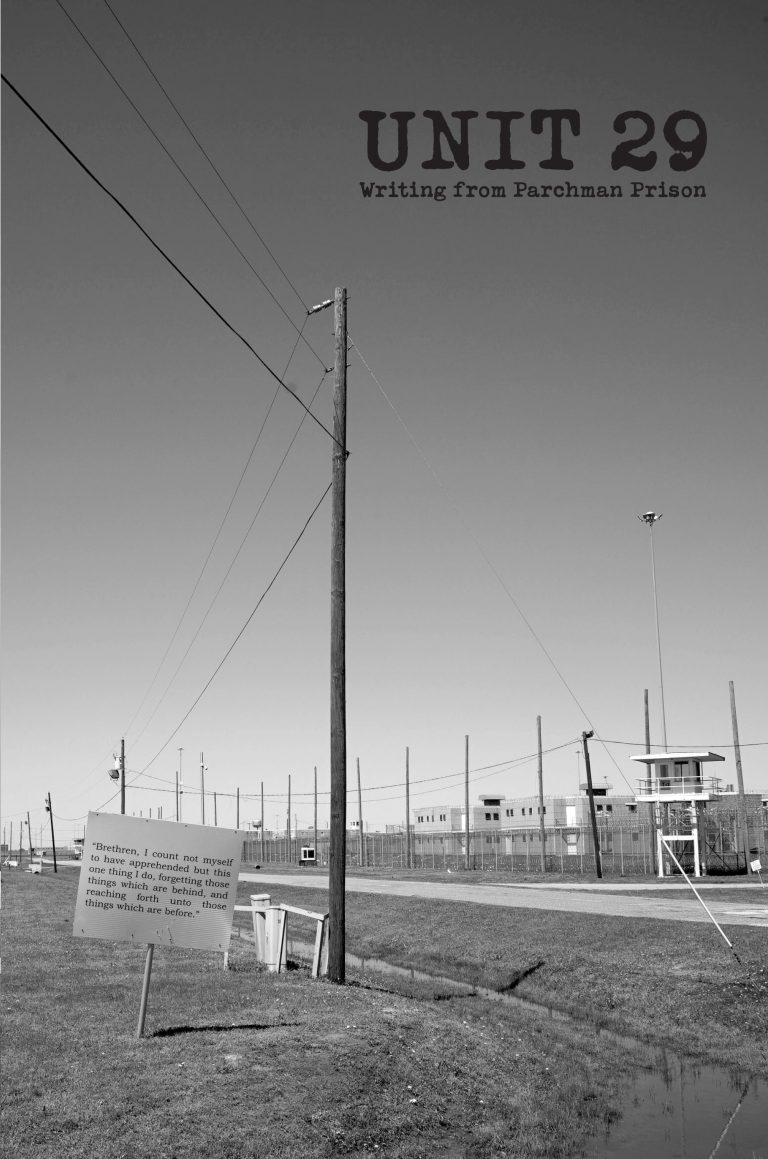

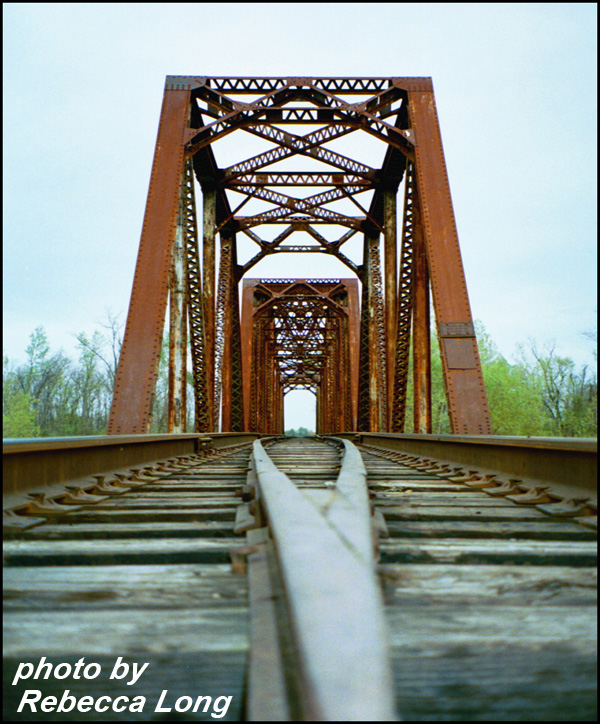

I drove just outside the city limits and parked in the same turnrow as always to visit “my” railroad bridge. It’s a swing bridge located on an active C&M track crossing the Yalobusha River. So, Step One is to park. Step Two is to walk across super old rickety railroad ties that aren’t evenly spaced for the first few hundred feet. The good news is that only walking half the bridge is required; Step Three is to stop at “The Middle” (what we’ve called this destination since I was 16).

I drove just outside the city limits and parked in the same turnrow as always to visit “my” railroad bridge. It’s a swing bridge located on an active C&M track crossing the Yalobusha River. So, Step One is to park. Step Two is to walk across super old rickety railroad ties that aren’t evenly spaced for the first few hundred feet. The good news is that only walking half the bridge is required; Step Three is to stop at “The Middle” (what we’ve called this destination since I was 16).

In the very center of the bridge is the main concrete support pillar, and on top of it lies the ironworks which used to spin the bridge for barges and whatnot to pass through. It’s easy to monkey-climb down the ironworks onto the concrete pillar and delightful to hang your feet out over the Yalobusha.

So about 11:00, we were hanging our feet, smoking weed, and drinking champagne “to celebrate the passing of my father’s suffering,” when I heard the unmistakable backup beep of a tow truck. Jonah called me paranoid for a minute (on solid grounds—I had once thrown my favorite pipe off that bridge because I thought a sheriff was spotlighting us—turned out to be a train). But I popped my head up again just in time to see my Daddy’s truck being towed away. At that point, I could have jumped up and yelled for them not to tow it, but they would have ignored that request, further charged me with trespassing on railroad property and public drunk, and I’d lose another pipe to the river.

So we stayed at The Middle, though we immediately climbed off the exposed concrete to hide amongst the defunct, camouflaging ironworks underneath the track. Once tired of crouching down, we returned to the edge of the pillar and realized after the sheriff’s car had passed by with a spotlight a few times that they could not indeed see us sitting there, and that they were too lazy to get out of the car and come closer.

They kept driving by for what seemed like an eternity after the truck was towed, though it was probably only 30 minutes. But we disregarded them anyway, since we were apparently invisible, and consumed most of the intoxicating substances we had with us while we reminisced over old times and caught up on more current times. I hadn’t forgotten that I had to deal with the truck, but spending time with an old friend possessing a commensurate soul and lifestyle, after one of the worst weeks of my life, was more important than being in a rush for more unpleasantness.

They kept driving by for what seemed like an eternity after the truck was towed, though it was probably only 30 minutes. But we disregarded them anyway, since we were apparently invisible, and consumed most of the intoxicating substances we had with us while we reminisced over old times and caught up on more current times. I hadn’t forgotten that I had to deal with the truck, but spending time with an old friend possessing a commensurate soul and lifestyle, after one of the worst weeks of my life, was more important than being in a rush for more unpleasantness.

A few hours went by—some of that time spent sobering ourselves a little—and our cigarette supply dwindled, so we decided to walk about two miles to the highway and, once there, maybe catch a short hitchhike (a mile, tops) to the towing place. I wasn’t about to call my mom, or let Jonah wake up his folks.

After we’d been walking for about 30 minutes, a sheriff car passed us, headed towards town, and didn’t stop. We thought, WTF? Ok. It turned around once out of our sight and returned a moment later. The officers questioned us and I told them we were walking to town since my daddy’s truck had been stolen. One of the two had known my father and that he had passed that week. But he just told us that the truck had been towed and where to find it, and when I asked if we could get a lift, he said no, that it was against policy. “To Serve and Protect” is definitely not decaled on the side of their cars.

We walked on, calling the tow guy as the walk quickly turned into a trudge. After several moments on the phone and many protests from a guy we’ll call D.B., it was decided that if D.B. wanted the $150 he was demanding, he needed to come fetch us from a mile and a half down the road. I gave D.B. cash and got my G.D. keys, driving Jonah home and then home, to my mom’s house.

We walked on, calling the tow guy as the walk quickly turned into a trudge. After several moments on the phone and many protests from a guy we’ll call D.B., it was decided that if D.B. wanted the $150 he was demanding, he needed to come fetch us from a mile and a half down the road. I gave D.B. cash and got my G.D. keys, driving Jonah home and then home, to my mom’s house.

We had what would have been our Thanksgiving lunch the next day. I wasn’t going to tell my mom what happened, just let it vanish, but she dragged it out of me—she knew I was upset about something (despite that morning’s consumption of the quarter of the solitary bar of Xanax I somehow—thankfully—managed to make last for the four-day hell week). She shook her head, was glad I didn’t get arrested, and let it go when I asked if I could help her make the stuffing and get the table ready. My brother-in-law, also in the towing business, swore he was going to tear D.B. a new one and get some money back for me, but I guess that never happened, which is fine.

We left the head of the table empty for my daddy that morning. I can’t remember if there was a place setting or not—I think that probably would have been too much. It was too much for my mom and sister when I put pennies on his eyes when he passed at the nursing home (they made me remove them, but the few moments were certainly enough payment and time for Charon to ferry him to the afterworld). We were all saddened, but relieved that he wasn’t trapped inside a body with a mind that had forgotten how to live—he had Alzheimer’s. He was a good man and a hell of a father.

“Thanksgiving” lunch was delicious (always, at mom’s house) and we were indeed thankful for the time we had together that day. And I think we have appreciated each other’s time together ever since—it’s a shame to think we were ever any less than happy to have family time. It’s important, seemingly more so as we all grow older. We share blood—we’re alike—whether we share the same political views or live the same lifestyle or not. Just as Jonah and I are kindred souls, my family is quite literally kindred—the natural affinity is a different sort, but the tie is still there. I wouldn’t trade the 24 hours after my daddy’s funeral for anything—I learned too much about life to abolish those memories. But I sure would like that $150 back. ![]()