Slavery. The Spanish Inquisition. The Salem Witch Trials. Nazi Germany, the Ku Klux Klan, the subjugation of women, and the Twin Towers. It should be no surprise that when we think on the negative effects of religion, we are left with a bitter taste in our mouths. How can the religious (those who claim that morality, ethics, and the sacred are well-founded in religion) care so little for their neighbor? I think maybe it has to do with mankind’s struggle to know (or not know) with certainty the Omnipotent and Unknowable. In truth, there are people in both theistic and atheistic camps alike fighting for uniformity, but can unity ever exist without uniformity? Can there be some sort of peaceful solidarity that presents itself as the solution to our problems?

Slavery. The Spanish Inquisition. The Salem Witch Trials. Nazi Germany, the Ku Klux Klan, the subjugation of women, and the Twin Towers. It should be no surprise that when we think on the negative effects of religion, we are left with a bitter taste in our mouths. How can the religious (those who claim that morality, ethics, and the sacred are well-founded in religion) care so little for their neighbor? I think maybe it has to do with mankind’s struggle to know (or not know) with certainty the Omnipotent and Unknowable. In truth, there are people in both theistic and atheistic camps alike fighting for uniformity, but can unity ever exist without uniformity? Can there be some sort of peaceful solidarity that presents itself as the solution to our problems?

I sometimes wonder if the non-believer thinks of God like the average American thinks of the banking industry: an evil conglomerate being sustained by the people’s wealth while withholding the truth from them, using and misusing them along the way. If we ask any random person to define Christianity what we’ll usually hear are words loaded with preconceived dispositions regarding the worst that religion has to offer. In spite of this, Christians by law of “adapt or die” must now separate their faith from religion and promote a type of “religionless Christianity,” a term coined by the late Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

sometimes wonder if the non-believer thinks of God like the average American thinks of the banking industry: an evil conglomerate being sustained by the people’s wealth while withholding the truth from them, using and misusing them along the way. If we ask any random person to define Christianity what we’ll usually hear are words loaded with preconceived dispositions regarding the worst that religion has to offer. In spite of this, Christians by law of “adapt or die” must now separate their faith from religion and promote a type of “religionless Christianity,” a term coined by the late Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

The problem is that our psychological motive, be it religious or not, is to set ideas on a level of being beyond criticism/humor which allows for very few people who are actually just interested in truth. Instead of practicing a type of ethnocentrism when it comes to our beliefs, we must learn to simply see that, on both sides of the gun, our beliefs are simply beliefs rather than weapons of mass destruction that define the limitations and boundaries of relationships and community. So, instead of working to destroy the psychological “other,” let’s take the human condition under the microscope and figure out exactly what it is that makes us react violently when projecting certain fears unto other ideologies.

The problem is that our psychological motive, be it religious or not, is to set ideas on a level of being beyond criticism/humor which allows for very few people who are actually just interested in truth. Instead of practicing a type of ethnocentrism when it comes to our beliefs, we must learn to simply see that, on both sides of the gun, our beliefs are simply beliefs rather than weapons of mass destruction that define the limitations and boundaries of relationships and community. So, instead of working to destroy the psychological “other,” let’s take the human condition under the microscope and figure out exactly what it is that makes us react violently when projecting certain fears unto other ideologies.

As far as this “religionless Christianity,” where we give up our dogma and tradition for the sake of our neighbors, our efforts should be wrapped up in awe for everything around us (the scientific pursuit) and of love for everyone around us (the religious or “Christal” pursuit). So, what does this mean for the future? Maybe it means instead of praying before a meal to showboat our religious fervor, we work to understand what loving our enemies really means and not using our tradition and our dogma to pit an “us against them” war.

Let us remember that the accounts of Jesus (be it historical or recorded in the gospels) show clearly that Christ did not intend to create a new religion but create a new kind of community and to challenge those powers that oppress and divide mankind in every society. Christ, instead of being glorified with his power and might, was glorified through weakness and suffering. Maybe, in the end, the death of God (this idea of a fascist, conglomerate god) can truly be our emancipation in the same way that the death of God was our salvation. Let us now begin to get outside our comfort zones, building relationships with people who have differing and challenging views and, most importantly, to love not in uniformity (when someone has finally begun to believe as we believe, or see as we see) but in unity.

Let us remember that the accounts of Jesus (be it historical or recorded in the gospels) show clearly that Christ did not intend to create a new religion but create a new kind of community and to challenge those powers that oppress and divide mankind in every society. Christ, instead of being glorified with his power and might, was glorified through weakness and suffering. Maybe, in the end, the death of God (this idea of a fascist, conglomerate god) can truly be our emancipation in the same way that the death of God was our salvation. Let us now begin to get outside our comfort zones, building relationships with people who have differing and challenging views and, most importantly, to love not in uniformity (when someone has finally begun to believe as we believe, or see as we see) but in unity.

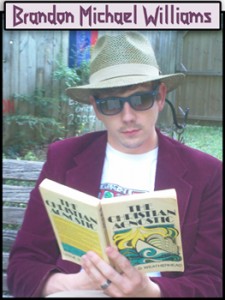

Brandon is a musician who enjoys community, listening to vinyl records, and reading religious/spiritual books. He lives in Oxford with his wife, Samantha, and works at Grisham Law Library of The University of Mississippi. Mr. Williams accepts all questions and comments. Feel free to contact him at brandon.brandonmichaelwilliamsAT gmailDOTCOM or visit his blog at www.brandonmichaelwilliams.net.

Brandon is a musician who enjoys community, listening to vinyl records, and reading religious/spiritual books. He lives in Oxford with his wife, Samantha, and works at Grisham Law Library of The University of Mississippi. Mr. Williams accepts all questions and comments. Feel free to contact him at brandon.brandonmichaelwilliamsAT gmailDOTCOM or visit his blog at www.brandonmichaelwilliams.net.

This article was published in The Local Voice #158 (June 14-28, 2012)… Click here to download the PDF of issue #158.