The Trials of Oscar Wilde

In the 1890s, Oscar Wilde’s poems, books, and plays were everywhere from London to New York, Sydney to Paris. The Irish-born Wilde was arguably the most famous person in the world.

Wilde was married with children but was also attracted to other men, and he openly (some say recklessly) engaged in same sex activities.

In Victorian England, same-sex sexual acts were illegal, punishable by two years in prison with hard labor. Wilde was known to sleep with young (17–20) lower-class boys—hotel attendants, delivery boys, bell hops, waiters—and he made no effort to keep it a secret.

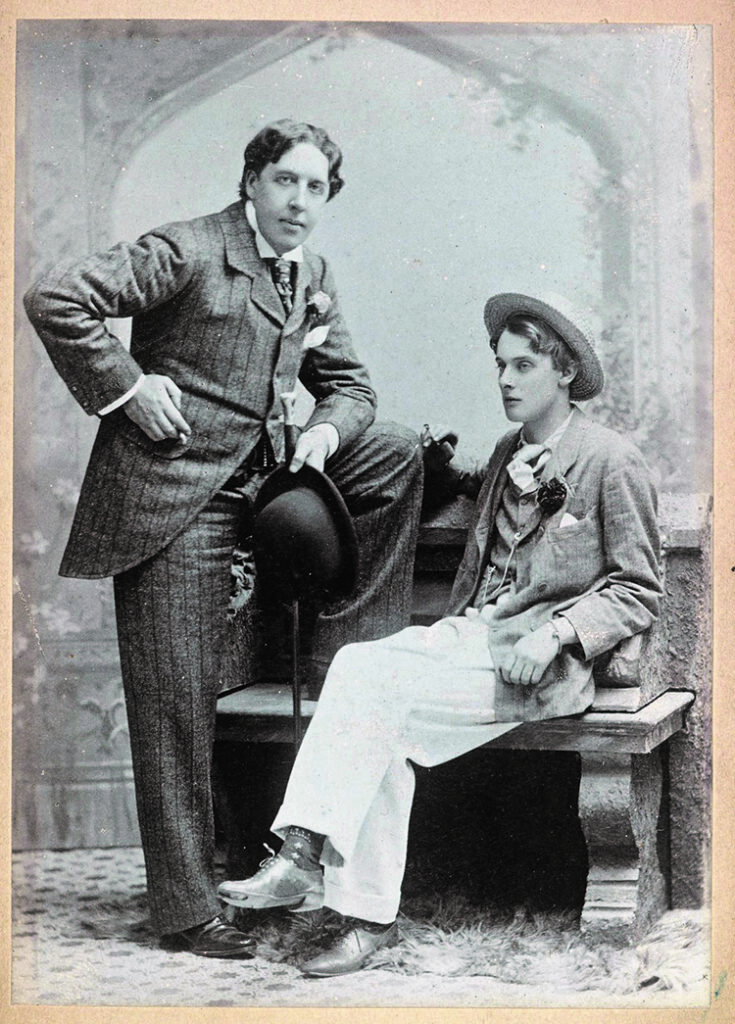

Wilde’s love was Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed “Boosy,” a 20-ish-year-old aristocratic son of the Marquess of Queensberry.

Queensberry was rugged type, a world-class boxer who developed the rules of boxing that are still used today. Queensberry did not like the fact that his son was romantically linked with the most famous man in the world and blamed the older, more sophisticated Wilde for Boosy’s sexual orientation (in fact, the opposite was true, Boosy taught Wilde to be unashamed of his sexuality). Queensberry publically called Wilde a sodomite.

Wilde and Boosy hated Queensberry and took the opportunity to punch back. Wilde instructed his lawyer to sue Queensberry for criminal slander. Wilde’s lawyer reminded Wilde that the statement was true, but Wilde figured that, since he and Boosy would deny their sexual relationship, the lawsuit was a good idea and filed the lawsuit against his lawyer’s advice.

The trial was like the O.J. Simpson or Johnny Depp/Amber Heard trial of its day. Newspapers and tabloids around the world covered every word of it.

Wilde and Boosy denied a sexual relationship and said Queensberry could not prove otherwise. Queensberry’s lawyers conceded that point, but then they started calling as witnesses the delivery boys, hotel attendants, bell hops, waiters—the lower class young men that Wilde had slept with—to testify in graphic terms that calling Wilde a “sodomite” was 100% true, not slander in the slightest.

Wilde’s lawyers tried to paint these young men as liars, but then Queensberry’s lawyers called hotel maids and other witnesses from the servant class who testified about Wilde’s not-so-secret lifestyle (a lifestyle Wilde should not have had to keep secret, assuming his partners gave valid consent, but Wilde himself was denying that lifestyle in his slander lawsuit).

Wilde lost his slander lawsuit and, in the process, publically proved he had engaged in sexual crimes. The Courts could not turn a blind eye or it would look like it was playing favorites to the rich and famous, and Wilde was charged with “buggery,” i.e. sodomy, shortly after the slander lawsuit was over.

Boosy immediately took off to France, outside of English law jurisdiction. Wilde was notified of his pending arrest, and his arrest time was scheduled for several hours after a ship to France was leaving out of London on the Thames River—an opportunity to escape to France, too.

But Wilde stayed. At trial, the Judge tried to help Wilde out and told the jury that it was hard to believe that Wilde, the brightest, smartest person in the world, was so dumb to openly and recklessly commit the crime of buggery with strangers he could not trust and leaving witnesses to boot. With the Judge’s help, the jury could not make a decision in the first criminal trial; but Wilde was tried again and public outcry against the Judge’s favoritism caused the Judge to withhold help in the second trial. Wilde was convicted, sentenced to two years in prison, but the Judge took it easy on Wilde and did not sentence Wilde to the standard “hard labor” punishment.

Wilde was treated like a celebrity in prison, given a private cell and allowed books, writing supplies, special food, and unlimited visitors. Wilde moved to France after release and lived the life of a Victorian aristocrat until he died of meningitis at the age of 46.

In modern times, the criminal trial of Oscar Wilde is cited as an example of discriminatory prosecution, and that is accurate, to an extent. It should not be ignored that no one went looking to prosecute Wilde for his sexual activities—Wilde opened up that can of worms himself in an ill-advised slander lawsuit. Also, it is rarely mentioned that Wilde was given special treatment throughout the process—opportunity to escape, helpful Judge during trial, light sentencing, and special treatment in prison.

Modern people often portray the prosecution as the criminalization of Wilde’s consensual relationship with Boosy, another aristocrat, but Wilde was actually on trial for his relationships with lower-class boys over whom Wilde held social and economic power, and many of those relationships would be criminal today on the issue of consent.

Perhaps this is a cautionary tale of failing to follow your lawyer’s legal advice—find a lawyer that you trust and follow his or her advice on legal matters. The trials of Oscar Wilde aside, do yourself a favor and read or watch a production of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. Timelessly witty and funny. I am sure Queensberry hated it.

Mitchell Driskell practices law with the Tannehill & Carmean firm and has been an Oxford lawyer for twenty two years. You can call him at 662.236.9996 and email him at mitchell@tannehillcarmean.com. He practices personal injury law, criminal law, and family law.