A few weeks ago, a secret tunnel that runs between the lowest level of what is now City Hall and the phone booth at the corner of East Jackson and Courthouse Square was discovered. Prior to 1885, when the structure was built to serve as the Federal Building and Post Office with a few jail cells tucked away in the basement, Homer Ox had a root cellar there where he and his fiancée, Native American Pontiac Ford, had secret rendezvous. (The town was actually named for Ox and Ford, but that’s another story for another day.)

The tunnel was dug during the Civil War as a repository for secret documents and emergency munitions. It was found through a vague reference in the will of an obscure Oxford resident, the Civil War veteran and cousin of Princess Hoka, Chief Crooked-Tongue Patawfa (1850–1965, give or take). Amid the documents safely stored in hermetically-sealed mayonnaise jars were ole Crooked-Tongues’ chronicles of disasters that occurred in the long-forgotten early days of the Double Decker Arts Festival.

The first Gone-But-Not-Forgotten (GBNF) event was held in 1865 to memorialize the 1864 burning of Oxford. Townspeople gathered to sing, pray, and otherwise honor the dead. Disaster struck when the juvenile delinquent Baer boys decided it would be funny to shoot off a bunch of fireworks at the end of the singing of “Dixie Land,” when everyone shouted “The South shall rise again!” resulting in the trampling deaths of 17 innocents and six of questionable character. The Baer boys were tried and found not guilty due to the precedent-setting “boys will be boys” defense. They were, however, publicly whipped on the Square with their pants down at every GBNF event for the rest of their lives. After the death of the last Baer in 1902, a reenactment of the whipping, called “The Beatin’ of the Baer Butts,” became a staple of the annual GBNF event.

In 1873 a fancy-pants chef came to Oxford to test the waters for a restaurant specializing in gourmet locally-grown foods. The Yankee scalawag planned to introduce his delicacies of collard greens, chitterlings (upscale for “chitlins”), and flash-fried cornbread at the GBNF. Disaster struck when one of his employees used the slung-clean technique on a ten-foot long chitterling packed with swine poo. As he slung the poo-tube like a lasso, huge poo pones were hurled out and plopped into the deep fryer, knocking it over and spreading deep-fried footlong poo pones everywhere. The chef hastily skewered the poo pones with sticks, shoved them back into the chitterlings, dipped them in the pot likker, deep fried them again and sold them under the name “Double Deep Fried Pot Likker-Dipped Chitlin’ Surprise on a Stick.” The chef was summarily run out of town that evening. He returned to New York City where he amassed a fortune selling his new delicacy to the elitists.

In 1899 the Carpenter family, local musicians and wood smiths known for their pre-fab Never-Fail Gallows, used one as a stage for the annual GBNF pageant. The Carpenter Family Band took their seats on stage and played. One-by-one the contestants sashayed across the stage in their oversized hooped skirts, ringlet wigs, and heavy make-up, looking more like the “ladies” that worked in Miss Kitty’s House of Chills an’ Thrills on South Lamar than beauty queens.

All was well until the final contestant, Miss Scarlett-Magnolia Bovina, appeared. Miss Bovina lumbered to center-stage, an oversized thorn among roses. The Carpenters had reinforced the Never-Fail Gallows with steel rods and removed the trap door mechanism which contained a vital piece of hardware that held the trap door up. The stage creaked under the weight of the rotund Miss Bovina. The trap door suddenly splintered and she plunged through, all the way up to her hips. The Carpenters scrambled for the stairs and the contestants leapt off the stage, their landings softened by their hooped skirt parachutes that made them look like the good witch Glenda in angelic descent into Oz.

The crowd gasped. For ten or so seconds Miss Bovina seemed suspended in mid-air. Then, like a greased pig, Miss Bovina’s hips dislodged and she plummeted all of fifteen inches. She grabbed two steel rods that had popped up through the stage on either side of the trap door and held on for dear life—long enough for copious bales of hay to be arranged below her. When she loosened her grip the impact of her plunge was softened, averting complete disaster. That is how Miss Scarlett-Magnolia Bovina became the very first Steel Magnolia.

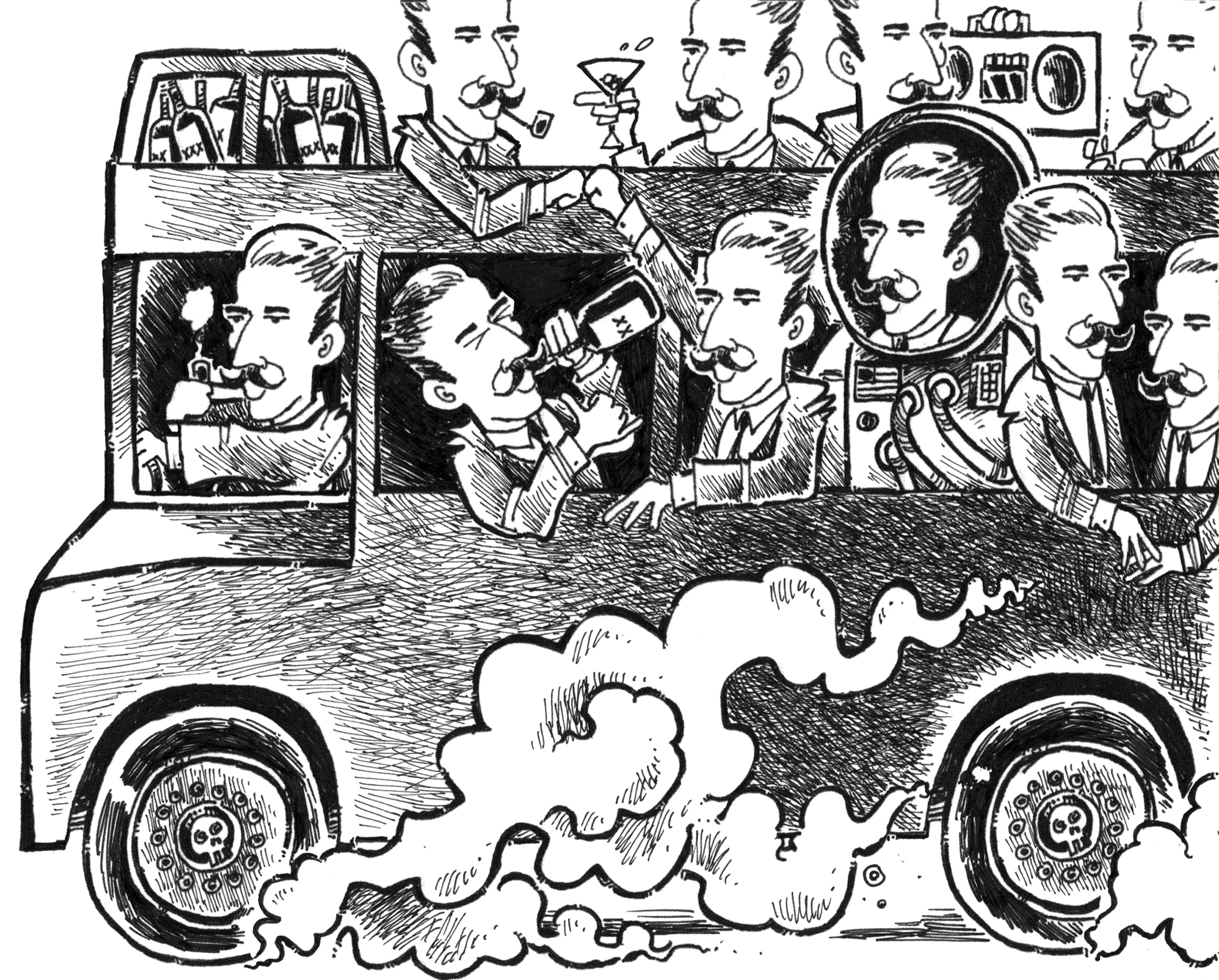

There were other catastrophes through the years: the tornado that made the head on the statue of the Confederate soldier spin like a roulette wheel; the food fight remembered as “The Battle of the Great Turkey Legs”; the failure of the first carnival ride, Quasimodo’s Escape, a zipline between the top of the courthouse clock tower to the steeple on St. Peter’s Episcopal Church; the saga of the runaway top-heavy double decker bus; to name a few.

Enjoy this year’s DDAF, but be on guard. Pictures are being taken from the sky and the NRA has declared open season on drones.

In two weeks: “The Untold History of the DDAF.”