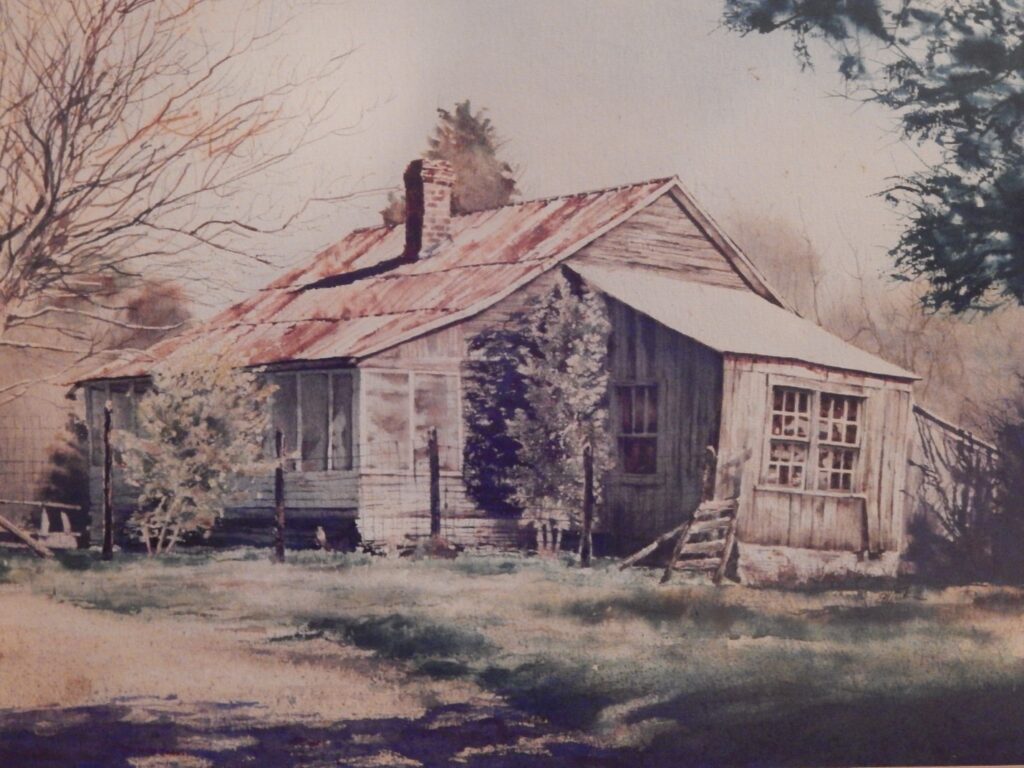

When I was a boy my grandmother told me I was just born an old man. Of course grandmothers don’t lie, so I knew it had to be true, but I didn’t understand it then. Now, a grown man—at seventy, even an old man—though not yet having achieved my grandmother’s wisdom, I still don’t know what she meant or why she said it. Maybe she said it because I’ve always liked old things—drafty old houses, decrepit barns, silent dusty churches, and cemeteries in the dead of winter. I like musty old books, records that go round and round on a record player, and old TV shows that held true to the verities of love and honor, sacrifice and duty, where the good guy always wins, but only after learning a lesson. I like doing many things the old way—pouring cornbread batter into bacon grease sizzling in a cast iron skillet, hand cranking a freezer of fresh peach ice cream, fishing for bream or perch from the pond bank with a cane pole. I sit surrounded by modern inventions—a computer, a laptop, a tablet (definitely NOT my grandmother’s letter writing tablet), a cell phone—all waiting to record my thoughts as ones and zeroes on unimaginably small transistors. I prefer my fountain pen. It may stain my fingers with ink, but it connects them to the paper (itself an ancient invention), paper that then touches someone else’s hands.

I like remembering. I can’t help but wonder if—even hope that—by remembering we are remembered, that remembering solidifies the fluid past. I wanted to say that remembering keeps the past alive, but even educated Yankees know Faulkner’s words: The past is never dead. It’s not even past. For them and perhaps many others those words represent an interesting intellectual exercise, but Southerners, especially Mississippians, know those words to be true. We know that behind the shimmer of an August afternoon, all that was still is, that beneath autumn’s leaves and winter’s frost, the past awaits, unsummoned,ready to burst forth. It’s not so much remembering in fresh growth when spring comes.

Some people say that I remember too much, that I live too much in the past. To them I quote the words of another poet, not a decadent Southern gentleman but a New York Jew. Preserve your memories. They’re all that’s left you.