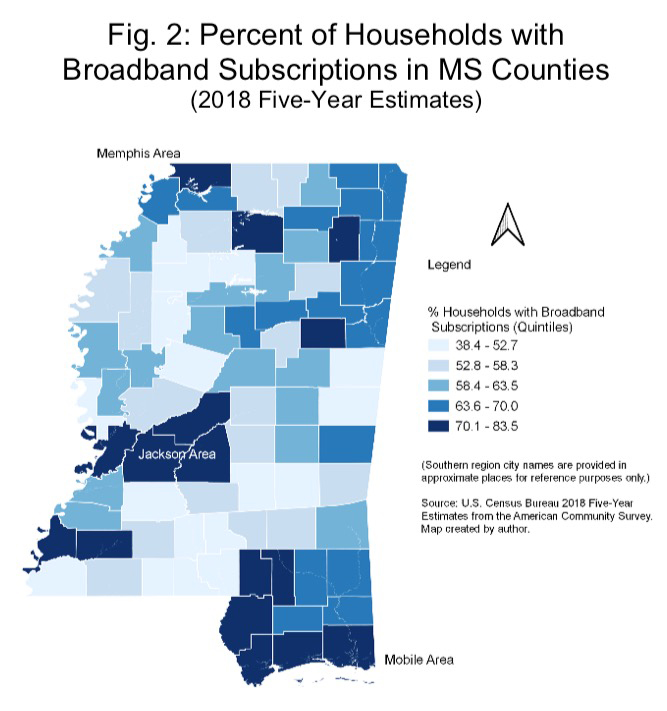

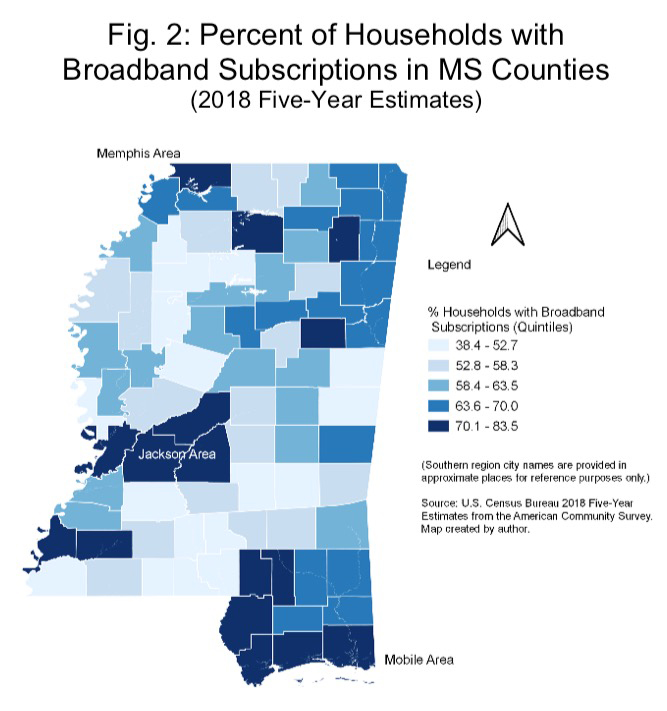

Better access to broadband internet service is one key to attracting and retaining working-age people in the state's rural areas. Graphic courtesy UM Center for Population Studies

Population researcher, political science professor examine possible outcomes from census

Shifting demographics and a general population decline in rural areas have created a real possibility that Mississippi will lose a congressional seat when data is compiled from the 2030 U.S. Census, a University of Mississippi population researcher warns.

Mississippi was one of only three states to lose population in the latest census, conducted in 2020. If this trend continues through the 2030 census cycle, Mississippi could be left with only three seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, said Anne Cafer, director of the UM Center for Population Studies.

A loss of influence in Washington would be felt if this happens, Cafer said.

“The loss of a congressional seat is a loss of voice,” she said. “Mississippi is an incredibly rural state, and half of our population is rural-based. The folks from Mississippi and all of its congressional staffs are the most attuned to the issues of rural people because most of their constituents are rural.

“To lose a seat means rural Americans lose a seat at the table.”

Data from the U.S. Census is used to establish the U.S. House of Representative districts, and the new data is used to redraw lines. The House has 435 voting seats, with each seat representing about 711,000 people. States each get two senators, regardless of population.

Mississippi’s largest population loss in the 2020 count was in working-age people, Cafer said. Generally, people are moving to areas with better amenities and economic opportunities that residents want.

The state’s small towns lost population, while larger, more populated areas, such as the Jackson metro area, the Gulf Coast and DeSoto County, saw growth in the latest census. Oxford and the surrounding area also have experienced steady population growth for the last few decades.

Between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, Mississippi lost 0.2% of its population. The new data shows that 64 of Mississippi’s 82 counties saw a decrease in population during that time, while only 18 counties recorded increases.

The following counties saw the largest population loss: Hinds County lost 17,543 residents; Lauderdale County, down 7,277; Washington County, down 6,215; Coahoma County, down 4,761; and Warren County, down 4,051.

Counties experiencing the largest gains were DeSoto, up 24,062; Harrison, up 21,516; Rankin, up 15,414; Madison, up 13,942; and Lamar, up 8,564.

Hinds County, with 227,742 residents, is the state’s most populated county, and Issaquena County, with only 1,406 inhabitants, is the least populated.

Workforce development to produce more skilled workers, in an attempt to lure employers, has been a focus in recent years. But the state needs better health care, stronger schools and more access to broadband internet technology in communities where those workers would live to help attract and keep them.

“If you are wanting people to relocate here, you have to make rural spaces in Mississippi attractive to young folks,” Cafer said. “They want hospitals and good schools and broadband.”

Bringing broadband internet into the communities that lack it is an important tactic to staving off some of the population loss and building back vibrant communities. Cafer’s office is involved in several projects to help expand the technology in rural areas.

“People will commute,” Cafer said. “I think the new model coming out of community development is that people will move to areas regardless of the type of job, if the community offers the kind of environment that is attractive – which includes access to services and leisure.

“They are moving to a place because of the amenities. They want to be there and they can see themselves staying there.”

Jim Steil, director of the Mississippi Automated Resource Information System with the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning, also has been involved with the census. He noted that the pandemic has affected counting, and counting rural populations has been historically challenging anyway.

It’s still somewhat hard to tell if Mississippi could lose a seat in 2030, but it’s definitely not likely to gain one, he said.

“Our potential gain or loss of a congressional seat in 2030 is largely dependent on the trending and 2030 population status of other states,” Steil said. “Caveats: A shrinking or statistically flat population is highly unlikely to ever obtain an additional seat.”

Marvin King, associate professor of political science at Ole Miss, has been watching the situation. He believes the population issues will become an increasingly hot topic for state political and business leaders in the next few years, as the 2030 census approaches.

“It is a wake-up call to our business and political leaders,” King said. “There is time to forestall it if the state can grow, but it needs to grow quite a bit. Economic development officials are working on it, but I do think everyone needs to realize the predicament the state is in.

“This a big, hands-on problem.”

From 1855 until 2003, Mississippi had five seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The 2000 census confirmed enough population loss to leave the state with only four.

Before the Civil War, Mississippi had as many as nine representatives, King said.

“It has been a steady decline ever since,” he said. “We were one of only three states to lose population in the latest census. This means we could go from having four out of 435 reps down to having three out of 435.

“This means our senators will be everything to us. We will have very little institutional clout in the House.”

This is noteworthy for many reasons. Perhaps largest, the House is where the appropriations process begins and major funding decisions are made, King noted.

States have dealt with a loss of clout, or have survived like Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Delaware, each of which has only one representative in Congress each. Fewer representatives from a state means fewer House committee assignments; therefore, less of a voice in the process.

With the need to maximize the impact of fewer voices in the House, establishing seniority will be critical for Mississippi’s elected officials to be effective, he said.

“This kind of incentivizes our voters to keep the incumbents in office,” King said. “I don’t want to say you are picking at scraps, but it is harder to make your state’s priorities known when you are institutionally invisible.”

By Michael Newsom