The deadline for Theatre Oxford’s 2014 National 10 Minute Play Contest is February 15, 2014, and writers from across the country are submitting their best short pieces in hopes of winning the coveted L.W. Thomas Award.

The deadline for Theatre Oxford’s 2014 National 10 Minute Play Contest is February 15, 2014, and writers from across the country are submitting their best short pieces in hopes of winning the coveted L.W. Thomas Award.

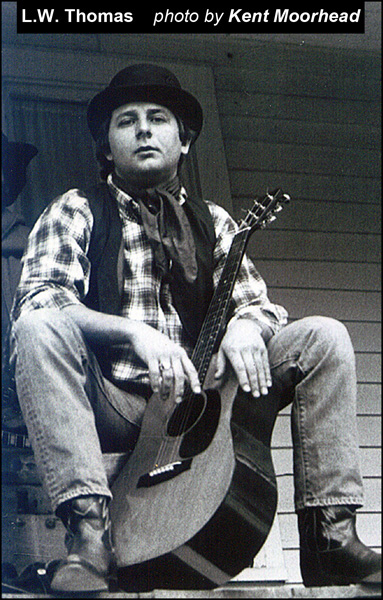

L.W. Thomas was one the most colorful and iconic figures ever to appear on the Oxford scene. A writer, actor and director, L.W. was a key player in Theatre Oxford for many years. According to publisher Neil White, the 10 minute play competition was established by him and L.W. in 1998.

“I’d read about a relatively new concept that had been developed by the Actor’s Theatre in Louisville, KY, the 10 minute play,” White said. “I mentioned it to L.W. He said, ‘I think I can do that,’ then, according to L.W., he went home and wrote a play (Talking to Jack) that not only lasted ten minutes, but took just ten minutes to write. When I proposed a national ten minute play contest, L.W. thought it was a great idea. He had starred in two full-length plays I wrote — Lepers & Cons and Paper (he also directed the latter). He said he would direct the winners, if I would produce them. I said ‘sure’. We had no idea whether it would catch on.”

“We produced the first winner in 1999,” White said. “The first winning play was directed by Jennifer Mizenko. Since that time, over 1000 original short plays have been submitted to the contest and nearly 90 have been produced in Oxford.”

Submissions can be mailed to: Theatre Oxford – 10 Minute Play Contest, PO Box 1394, Oxford, MS 38655. For more information, e-mail the Contest Director at 10minuteplaysATgmail.com (replace AT with ampersand when sending mail). Click here to read the contest rules.

Larry Wayne Thomas breezed into my life on a random wind, and we sailed together happily for many wonderful years.

Larry Wayne Thomas breezed into my life on a random wind, and we sailed together happily for many wonderful years.

We first met in April, 1976. I was a freshman at Ole Miss, where L.W. was teaching English. My roommate, a dissolute mental lightweight who went on to serve two spectacularly disgraceful terms in the Mississippi legislature, was his student. He paid me to write his term paper for L.W.’s class. Not only did I write it, but I was prevailed upon to deliver it to his teacher’s office at the last minute. L.W., a handsome young man in a tiny office in Bondurant, received the paper and my lame excuse about the roommate being called home due to a family emergency with undisguised ill-humor. The paper got an “A”, the roommate passed the class with a “C” and I walked away with thirty bucks. When I finally got around to telling L.W. this over twenty years later, he said, “I knew that idiot couldn’t have written a paper that good, but I couldn’t prove he didn’t.”

He and I came to know each other well during the intervening years, seeing one another around town, mostly at watering holes such as The Rose, The Gin or Ireland’s, among many mutual friends such as George Kehoe, Jere and Joe Allen and his future bride, Jean Tatum. L.W. began working at The Warehouse about that time while I bounced from one ill-fated restaurant to another. After the failure of Audie Michael’s, I found myself unemployed. Shortly after that, L.W. came to my apartment and offered me a job at the Warehouse. I don’t know whose idea it was, his, Frank Odom’s or Don Carlisle’s, but of course I took the job and for years he and I worked shoulder to shoulder in Oxford’s best-known and most respected dining establishment.

L.W. was my boss, the primary liaison between the kitchen and the floor, a job that’s bound to make anyone a nervous wreck, and L.W. was no exception. Busy nights reduced him to fussing and fretting to no end. My job, as I saw it, was to keep the kitchen working smoothly, which involved a minimum amount of interference from management. L.W. and I had our disagreements (most notably over his insisting on adding bell peppers to a shrimp boil), but after the last tables were served, everything was rosy. Outside the kitchen doors, with his droll wit and unfailing good humor, L.W. was the most congenial, amiable restaurant host possible. He knew everybody and everybody knew him, and (for the most part) their knowledge of one another was infused with warmth and life. L.W. and I usually travelled in different circles, but we would often bend elbows together; he was smart, funny, a joy to be around, and I basked in his company. I began to call him Uncle L., a sobriquet some of our friends adapted as well, to his wry amusement.

The morning after the Warehouse burned, twenty-seven years ago this February, we met one another on the northeast corner of the Square and walked east on Jackson Avenue. We barely spoke until we got to the smoking ruins of Country Village. We stood there for a moment, and L.W. gave voice to what was running through both of our minds: “It didn’t start in our kitchen.”

We both moved away after that; me to Florida, L.W. to Colorado. I returned to Oxford after four years and re-entered Ole Miss, but I got L.W.’s address from a mutual friend and wrote to him, saying how much I missed him and half-jokingly urging him to move back. Well, he did, and though I have a feeling that he was just as miserable in Colorado as I was in Florida and my plea was just added incentive, he later told me on more than one occasion that my letter made him so homesick he just had to return.

It wasn’t long afterwards that I moved from Oxford again. To my everlasting regret, I missed his wedding to Jean, and as fate would have it, I never saw my Uncle L. again. How I wish I could write him another letter and tell him to come back to us.

–