University of Mississippi doctoral student Kayleigh Mazariegos shows off some of the equipment she used to capture the sounds of underwater creatures in the Gulf of Mexico at the Mississippi Aquarium. Mazariegos partnered with the aquarium on the study, which aims to determine whether fish vocalizations can be used to identify various species. Submitted photo

Doctoral student uses noninvasive method to determine species found on reefs

Grunts, purrs, barks and knocks – it may be surprising to learn that these noises can come from fish. Known as fish vocalizations, these sounds are the subject of a new study at the University of Mississippi Department of Biology.

Kayleigh Mazariegos, a third-year doctoral student in biology, is leading a project to determine whether fish vocalizations can identify fish species. The Acworth, Georgia, native is focusing her research on artificial reefs in the Gulf of Mexico.

“I’m interested in artificial reefs because I used to fish them,” Mazariegos said. “Research on artificial reefs is limited. While people are able to catch fish on them, we don’t know their ecological role. We don’t know if they help increase fish and their relationship with ecological processes.”

Mazariegos received funding from the American Museum of Natural History and the university’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Research to conduct this work.

The research seeks to apply the principle of island biogeography to reefs, said Richard Buchholz, professor of biology and Mazariegos’ adviser. The theory examines why some islands have a certain number and diversification of species and others do not. However, specific challenges coincide with exploring this in the Gulf.

“The problem with the Gulf of Mexico is that you can’t put cameras down there because the water is too turbid and cloudy,” said Buchholz, who is also CBCR director.

“An alternative to catching is using acoustic sampling. It is a sophisticated method that has been used in animals like bats and birds for 10-15 years but hasn’t been widely used in aquatic habitats.”

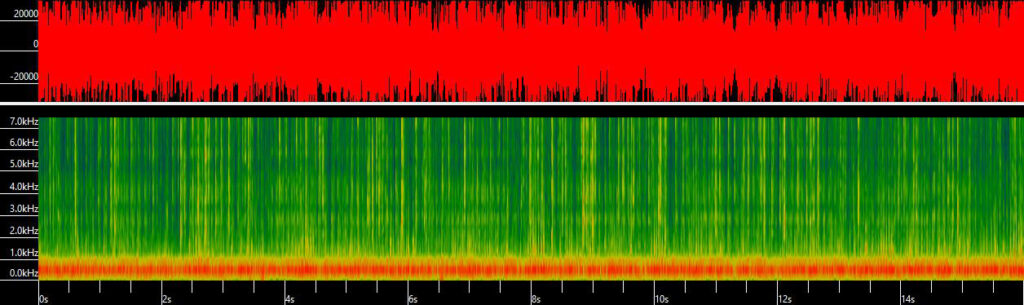

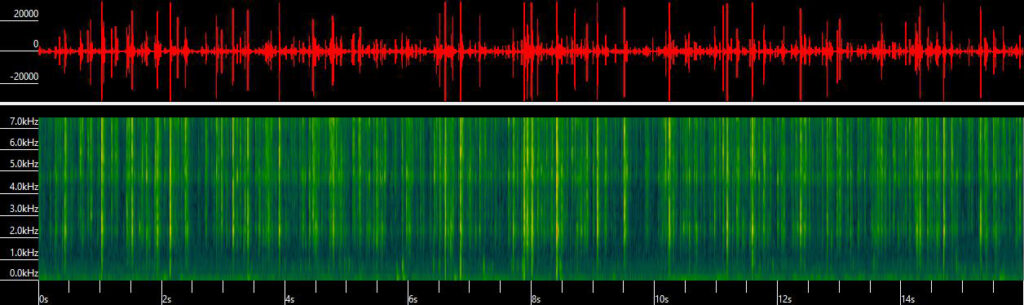

This summer, Mazariegos partnered with the Mississippi Aquarium in Gulfport to record the sounds of various species. She then placed small recording devices – about the size of a GoPro – on 12 reefs off Cat Island, a Mississippi barrier island.

Mazariegos is conducting a complex analysis of data from those weeklong recordings with help from the National Center for Physical Acoustics at Ole Miss.

“For some fish, you can get down to a specific family or genus, and others you can see that it’s this specific fish,” she said.

Despite just beginning to learn how to analyze acoustic data, Mazariegos expects her preliminary data set to spawn results by December.

An important element to the project is utilization of the GulfSeeLife app. The UM-developed app, funded via a RESTORE Act grant from the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, allows “citizen scientists” to record observations about plants and animals in the Gulf of Mexico.

Mazariegos is using the community science feature of GulfSeeLife to collect fish capture data that can be compared to the diversity of fish identified through acoustic recordings on the reefs.

The researcher said that her favorite aspect of the project is the noninvasive nature of this approach.

“The usual way is capturing them or using cameras,” Mazariegos said. “You could miss a lot because there are a lot of species that are more cryptic – they may be scared away or too small to be caught on hook and line.

“With vocalizations, you don’t have to have an eye on them, and you can tell what’s there based on how they are behaving naturally. I think it’s a good idea to make these data more accessible and easier to collect.”

The Gulf is still feeling the effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, plus consequences from unprecedented warm waters and the influx of tourists to its beaches, Buchholz said. Mazariegos’ efforts to determine the role of artificial reefs could have important conservation implications in the face of those challenges, he said.

“Artificial reefs could be constructed in a way that is helpful to biodiversity – to things that fish eat and even things that eat fishes,” Buchholz said. “If you can maintain that food web in the face of all those challenges to living things in the Gulf, then we can protect that biodiversity.”

This research is supported by the Lerner-Gray Fund for Marine Research of the American Museum of Natural History.

By Erin Garrett