Courtney Roper (right), assistant professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Mississippi, helps a student set up air quality samplers on the roof of Faser Hall on the Ole Miss campus. Roper and postdoctoral research associate Hang Nguyen recently studied air quality samples from across Mississippi to determine the rate of black carbon pollution in different locations. Submitted photo

Increase in cancer risk, climate warming associated with high concentrations of tiny particles

Two University of Mississippi researchers have found dangerously high levels of black carbon at several Mississippi locations, according to research published in the fall in the journal Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health.

Black carbon, commonly referred to as soot, is a contributing factor to global warming and poses health risks to populations exposed to it. The small air pollutants are released by activities such as driving vehicles, burning wood or fossil fuels and some manufacturing processes.

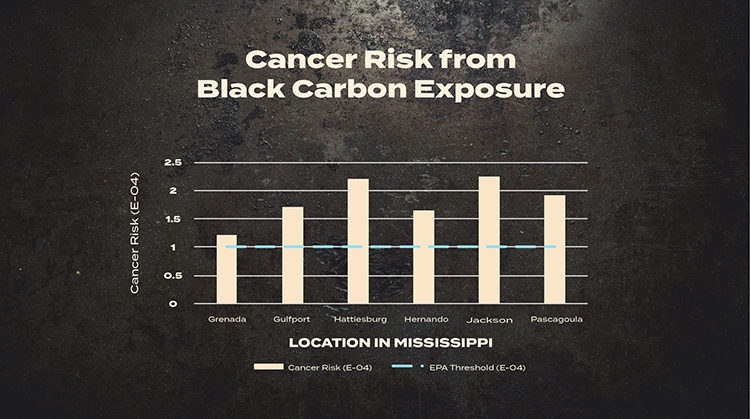

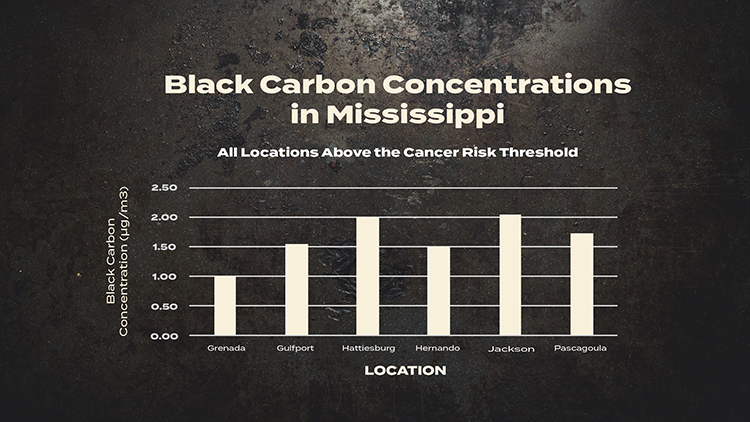

Researchers Courtney Roper, assistant professor of environmental toxicology, and postdoctoral research associate Hang Nguyen found that black carbon levels in Mississippi exceed health recommendations in Hernando, Grenada, Jackson, Hattiesburg, Pascagoula, and Gulfport, six locations surveyed by the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality.

“What we found in adults with that level of exposure to black carbon is above the EPA’s recommended threshold,” Roper said. “At all six locations, it was above the EPA’s threshold of what is a normal cancer risk.”

Black carbon is a component of PM 2.5 air pollution, which means that particles are 2.5 microns or smaller. This type of pollution is regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Approximately 4 million deaths worldwide are attributed to long-term exposure to PM 2.5 air pollution, which is also linked with increased risk of cancer, heart attacks, strokes and lung disease. According to the American Heart Association, Mississippi has the highest death rate from cardiovascular disease in the country, and the Mississippi State Department of Health reports that approximately 6,500 people die in the state each year from cancer.

Black carbon also contributes to climate change, Nguyen said. Black carbon absorbs light from the sun and releases that heat back into the atmosphere, causing greater warming effects than carbon dioxide.

Jackson, the state’s largest metropolitan area, had the highest concentration of black carbon at 2.04 micrograms per cubic meter.

Though soot is visible to the human eye, individual black carbon particles are approximately 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, smaller than a single grain of sand.

“The small size of black carbon allows it to penetrate very deeply into the respiratory system,” Nguyen said. “This can affect human health.”

Most black carbon pollution is created while producing energy for homes and commercial areas through coal, wood or fossil fuel burning, followed by transportation and industrial emissions, according to the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. Natural causes of black carbon pollution include wildfires and volcanoes, Nguyen said.

Not all of Mississippi’s black carbon originates in the state, however, Roper said. Because the lifetime of a black carbon particle is approximately two weeks, wind currents can carry black carbon from other states and even countries to Mississippi.

“Air pollution doesn’t have state boundaries,” Roper said. “Wildfires in Canada can affect air quality in Mississippi.”

Roper and Nguyen studied air samples the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality collected between September 2013 and December 2014.

“The reason we care about this is black carbon has known human health effects,” Roper said. “Black carbon is specifically health-relevant and relevant to climate change.”

The Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality releases its air sampling data years after collection, meaning Roper and Nguyen’s research is based on data that is more than 10 years old. Roper said she hopes in future research to gather real-time data about black carbon emissions in the state to better understand the health and climate risks in Mississippi.

“One of the reasons we want to continue this research is we’re taking a snapshot,” Roper said. “Maybe black carbon levels have dropped substantially or increased substantially since then.

“But the more data that we can collect on this, the more we can make better estimates of the risk of these things.”

By Clara Turnage