Lee’s short film has won multiple indie awards and features a who’s who of local VIPs.

Few authors have a more rabid fanbase than Stephen King, and his stories and novels have been made into dozens of movies and miniseries. Most of these have been mainstream, such as The Green Mile, Misery, The Shining, It, and Pet Sematary.

However, lurking in the film world are a handful of short films created by up-and-coming film students, made possible by a program called “Dollar Baby” deals in which King grants permission to these students to adapt one of his short stories for $1.

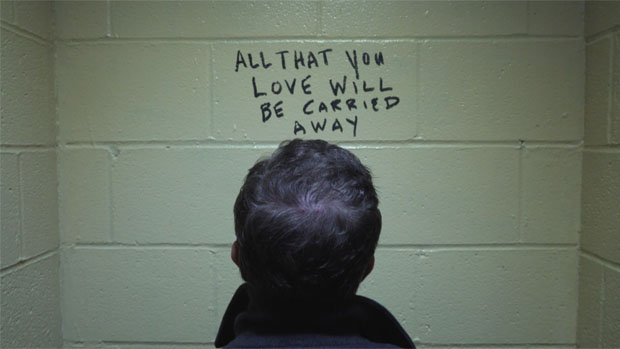

Thad Lee, local filmmaker and longtime friend of The Local Voice, is one of those lucky few. His adaptation of “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away” was finished in time for this year’s Oxford Film Festival (OFF), but in Oxford, the big screen has evaded the work due to the festival’s move online following the pandemic.

“All That You Love WIll Be Carried Away” was included in OFF’s virtual film festival as part of the McPhail Block earlier this summer, and now fans will have a chance to see the film at the OFF to the Drive-In pop-up theater on Sunday, August 16, where it will screen right before the feature Shawshank Redemption, another King adaptation.

Lee’s film has already made waves in the festival circuit, winning “Best Thriller” at the New York Film Awards and six awards at the Los Angeles Indie Short Fest (Best Short Film, Best Indie Short Film, Best Director: Thad Lee, Best Actor: Rhes Low, Best Cinematography: Matthew Graves, and Best Adapted Screenplay: Thad Lee), among many other accolades.

One stipulation of the Dollar Baby Deal is that the film may only be shown publicly for one year after completion, so this could be your last chance to view it. We hope the Malco will reopen in time for another showing before February 2021, but just in case, make your plans now to be at the Drive-In on August 16. The Cannon Lot, located at 100 Thacker Loop in Oxford, will open at 8 pm, and Lee’s film will begin at 8:30. You really, really don’t want to miss this one! GET TICKETS HERE

Naturally, we had plenty of questions for Thad, so keep reading for all the juicy details, and get your drive-in tickets at https://oxfordac.eventive.org/.

Tell me more about Stephen King’s Dollar Baby Deal? Why were you attracted to the program? Did you have to submit an application, proposal, etc?

I was finishing up a long-delayed MFA in screenwriting at the University of New Orleans, and one day I broke up thesis-writing sessions by driving to the Barnes and Noble in Metairie to take advantage of their 50% off Criterion Collection sale.

While I was there, I browsed the magazine stand and saw The Complete Guide to Stephen King, which I believe covered every feature film and television adaptation of his work. The Shawshank Redemption article touched on director Frank Darabont’s first film, “The Woman in the Room.” It was a Dollar Baby, which is a deal King offers film students, who can acquire the rights to one of his short stories for one dollar. One of the catches is the filmmaker cannot sell the film. Another is that it can only have a one-year life after completion to be publicly screened. Still, I thought the idea of King giving film students a chance to work with his material was interesting and generous.

After I defended my thesis, I drove here to Oxford and talked to Carlyle Wolfe about my future. The aughts had kind of been a lost decade for me, and she suggested that I might make a film to steer my career back in line. I knew she was right but couldn’t afford to make anything longer than a long short. I left her to go visit my parents in Hattiesburg for Thanksgiving. As I was driving, I brainstormed possible short film ideas that I could carve out of some of my feature scripts. None of them really seemed to fit into the shorter shape.

Then I remembered the Dollar Baby. Graduation was two weeks away, so while I was still technically a student, I found King’s website and browsed the available Dollar Baby story summaries. I applied for “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away,” mainly because it seemed the least spooky. A day later, I received word from King’s people that I had the rights to the story, as long as I signed the contract and sent the dollar. I did, and here we are.

How did you select which short story you wanted to adapt to film? Were there any restrictions in place—such as which stories you could use; how much you could alter the plotline, characters, setting, etc? Did you get any feedback from King’s company about your finished product?

There was a selection of short stories that I had to choose from, and I believe they change somewhat regularly. Each one had a little summary, so I read them all. Most of them were classic Stephen King nightmares, but I didn’t want to make a horror movie. I knew I could put my energy into the one-line summary of “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away,” which was: A man checks into a Lincoln Nebraska Motel 6 to find the meaning in his life. It wasn’t until a week later that I got a copy of the book and realized that the story was about bathroom graffiti and suicide.

There were no restrictions that I read concerning how to adapt the story. It is a real licensing deal. You pay for the property, and it is yours to remake. That’s probably why the restrictions on the exhibition end are so stern. There have likely been some real Dollar Baby lemons. You can’t put them on You Tube or screen them outside a film festival, so if it doesn’t play at festivals, it won’t be seen.

As far as feedback from King’s company, I haven’t sent him his copy yet. I know I need to, but part of me wants to send it closer to the end of the year, when the film’s one-year life is all-but-over. That way I can tell him in a letter how the project fared in the world. And I hope he likes it.

I watched your film at the beginning of the virtual fest when it was in the McPhail Block. I watched it again a couple nights ago and I also read the short story. The main difference is Johnny’s character as the narrator. Tell me a little about the screenplay adaptation and how you approached writing it.

When I read “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away” for the first time, I was concerned about how dependent the story was on the narrator. If I had constructed it the way it was written, the film would pretty much have been the Salesman staring at a notebook in a hotel room surrounded by voice-over. I wanted to make something more cinematic, but I also didn’t want to lose the rich interior that the narration provided, so I created Johnny’s character, the Traveler, to be that voice. Going there helped me create an origin story for the graffiti-filled notebook that is central to King’s story.

Talk about some of the techy details about the film? Any funny stories on set? Significant setbacks?

I really wanted to weave as much of the language and settings from the story into the film as possible, so I was dead set on actually filming in a Motel 6 in Nebraska. I used Google maps to get overlook views. None of them really seemed to match up with one in the story that backs up to a farm. Then I realized all the cast and crew I wanted, with the exception of cinematographer, Matthew Graves, lived in Oxford or Memphis. Paying for their travel for a week in the dead of winter to the Midwest became obviously asinine, particularly for a little film like this one, which had no way of ever making a dime.

So, I spent about a week driving to every Motel 6 between Pine Bluff, Arkansas and Pulaski, Tennessee; taking pictures, scouting the landscape, and talking to the people who ran the hotels. The one in Pulaski was a real contender. It backed up to a corn field, and its owner wanted ten rooms booked for a week. He put me in touch with Motel 6 Corporate. They wanted to know if the Motel 6 property, its employees, other guests, or their automobiles would be filmed. I sent them the script and the storyboards, which had the hotel, its employees, and other guests’ automobiles in honest sight.

I then sent them a standard location release but never heard back. I was disappointed, but it was really a blessing. It made me look at Clarksdale again. Its flat highways could be Nebraska. Its cornfields may not back up to a hotel, but we could cheat that. So, we did, and found the hotel we needed in Oxford at the University Inn. They let us film in the lobby and in the parking lot with actors screaming at each other in the wee hours. No one seemed to mind. It was perfect.

But the thing I really hated losing more than anything about Motel 6 was its spokesman, Tom Bodett’s line, “We’ll leave the light on for you.” Our story ends with the Salesman’s life depending on whether or not he sees a farmhouse light across a field during a snowstorm. I wanted to work that into the film badly, just on signs on the wall or on No Smoking signs, so I wrote Mr. Bodett himself, thinking he’d get the story and maybe even wrangle me a little money from Motel 6 themselves to help make the picture. I am sure it was the weirdest email he has gotten in years, and I was surprised not to hear back from him.

Well, one night I told Carlyle I was changing Motel 6 to Hotel 7, and that I needed an advertising line that had light in it, something like “Hotel 7, a well-lighted place.” She said, “Oh, like the Hemingway story.” I didn’t know what story she was talking about, so she fetched it from her shelf. I read “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” later that night and felt a wonderful synchronicity between it and King’s story, for they are both about suicide. So A Clean, Well-Lighted Place became my hotel’s catchphrase.

Next I made a crude logo, which insulted Carlyle’s creative sensibilities, so she had mercy on me and re-made it into something any motel chain in the world would be lucky to have.

Any special shout outs to your crew?

This was an ambitious shoot. There were lots of locations. There were lots of set ups at each location. We shot in June outside in the afternoon and February outside at night, so the weather was extreme. I can never say enough about the talent and temperament of Matthew Graves. He never got overwhelmed and delivered not only what is on the storyboard but also gave me some great ideas to consider that made it into the film. I hope he feels like this story is his, too, for it would look completely different without him. I am so glad I could lure him back to Oxford for two weeks.

But Greg Gray, Laura Cavett, Matt Wymer, and Parker Hobson, who was still in high school when she did makeup for us, were all dependable. They each made key contributions. As hard as we worked and as tired as we were when it was over, I think they’d all say it was a good set. Even when we had flat tires at midnight in little towns that don’t have streetlights.

Talk about some of the locations where the film was shot.

We shot at six locations in and around Clarksdale: the highway, a former gas station called Bruno’s Quick Mart (in Alligator), the Bargain Barn (in Tutwiler), Mount Horeb Church (in Claremont), which was the farmer’s field, and Morgan Freeman and Bill Luckett‘s Ground Zero Blues Club .

In Oxford we filmed at the University Inn, The Chicory Market, Blue Creek Cabin, the Oxford High School cafeteria, and Off-Square Books. I was really lucky to get that last one, for we needed a bookstore for a quick cutaway shot. Lyn Roberts sighed when I asked her and said that Richard Howorth really didn’t like film crews to interfere with customers’ browsing. I told her I understood and that we’d be out of there in fifteen minutes, and we were. That shot with Rebecca Jernigan is one of my favorite ones in the film. Where would Oxford be without Lyn and Richard?

Where were those bathrooms? Did you have to add your own graffiti?

The bathroom when the Salesman is younger is at Ground Zero, and 99% of that graffiti is theirs. We added our very crude Hellen Keller and Jim Morrison graffiti, but I didn’t want it to be permanent, so we wrote on Clear Ultra Cling sheets with magic marker and slapped it on the wall. I don’t think anybody took the sheets down. I wonder if they are still there.

The bathroom when the Salesman is older was at Wall Doxey State Park, though I am not sure if I should reveal that. The Cling sheets showed up on their yellowish walls, and we had to actually write the last two bits of graffiti on its walls. We scrubbed off what we could. I should really go back with some heavy-duty cleaner and finish the job. Carlyle thinks I need to repaint it.

Talk about some of the music and the score.

When I wrote the script and location scouted I had very specific songs on the stereo by people like Rev. Gary Davis, John Lee Hooker, Brian Eno, Vern Gosdin, The Statler Brothers, and of course, “As Long As I Can See the Light” by CCR. I had never officially licensed music in a film before, so I was a bit shocked and disheartened when I heard how much it would be just to get a festival license (which is one year and just festivals) from people in Los Angeles and New York who are in the business of licensing music for films. In the end, I could only afford one, so we got “Flowers on the Wall” by the Statler Brothers.

The rest of the music I had to replace, and boy, am I lucky I live in Oxford. Cary Hudson, Lyon Chadwick, and Eric Carlton, who helped me with films in the past came through again, as did musicians who I had never worked with before like Kell Kellum, Nate Robbins, and Winn McElroy, who was traveling with Moon Taxi and still delivered something that was better than what I was asking him to replace. And George Shelton! He let me use Jeffrey Reed’s great recording of “S.O.B.” from Black Dog Records’ Rock N Roll Summer Camp ’98.

I am also proud of the musicians who acted in the film. Austin Marshall was the Radio DJ. I knew he could knock it out because I filmed his and Newt’s interview with Cary Hudson for the Blue Mountain documentary on the Local Mail Radio Show the week of Double Decker, 2011. I told him I needed that golden radio voice, and he still had it.

Jimmy Phillips played the disgruntled Hotel 7 Manager. I knew that he once worked at the Inn at Ole Miss and thought he might be able to bring that experience with him to the film. I was on my way to the Inn in hopes that Jimmy still worked there. I stopped at The Chicory Market on the way for groceries, and Jimmy happened to be in there shopping. I gave him the script, offered him the part, and he said yes. His character was based on Bob, the hotel manager at the Knights Inn in Lebanon, Tennessee. That is where I stayed during the Great American Eclipse of 2017, partly to see if Ron Sexsmith’s description of the town held true.

I asked Bob if I would be able to keep my room another day, and he told me that the room was mine until the next morning and that as long as I kept paying him by the next morning that room would stay mine. When I asked him, “What’s that supposed to mean?” He said, “People have been here for years.” It sounded like a line fit for The Shining, so I included it into the script. We even got Pinter Office Supply to make our room keys replicas of The Overlook Hotel.

What is your favorite Stephen King story or novel? Film? Are you a fan?

Yeah, I am a fan because of the movies. “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away” is the only prose of King’s I have ever read that wasn’t a quote or tweet. I would like to read more, and I will at some point.

As the films go, I love The Running Man, The Shining, Misery, Stand By Me, The Green Mile, and most of all, The Shawshank Redemption. The scene where Andy Dufresne plays that duet from Marriage of Figaro on the record player is sublime. Oh, and I really liked The Dead Zone, Christine, Carrie, but not It. Both the new one and the one with Tim Curry are just too tough for me.

When did you start this project and how long did it take until completion?

I got the rights to the story the day before Thanksgiving of 2017. We shot the first part of the script in June of 2018. The Salesman was to have aged seven years between the two parts, so we took off till February of 2019 so that Rhes Low could get “in shape.” Matthew Graves and I finished a rough cut of the film in September of 2019. The final cut with all the licensing set came in around the time the film was first screened at the Black Hills Film Festival in South Dakota on February 22, 2020. It is crazy that it took that long to make a short film. It doesn’t feel like there was so much time between birth and completion. But I was also busy with other things like getting married.

You mentioned that you can only show the film publicly for one year after completion. How has the pandemic affected that deal? What are your plans to show the film? What is going to happen to the film after it shows for one year?

The pandemic has affected the release of the film tremendously in some ways. One of the reasons King started the Dollar Baby was because of the impact films made on him growing up. Making this deal with outsiders was a way to open doors for them that might not be open otherwise, so not being able to travel with the film and meet industry people who might be looking to give somebody like me writing, directing, or producing jobs in some ways sabotages the purpose of the Dollar Baby Deal, for it is so much about the year of exhibition.

On the other hand, we live in a remarkable time. The internet has made it possible for 24 of the 26 festivals to screen the film since late February. It has won awards or honorable mentions at eighteen of them, including five for Best Film. That doesn’t mean that I will be directing a feature film by the end of the year, but it is encouraging. And I will make a film. And after that I will make another film.

As far as what happens to the film after February of 2021? I guess it will be shelved, unless I get written permission by King to show it somewhere.

What were some of the challenges with making the movie?

I wore four hats on this film. The most pleasant was that of writer because I was alone and quiet. The editing job was hard because Matthew Graves lives in South Carolina and I live here, but we worked it out together. What made it endurable was knowing what we had in the can. Getting the most out of it is a grind, but in many ways the fight is over. You are piecing the story together the best you can, the way a reporter, historian, or detective might do.

Directing is hard and exhausting because the fight is with the story and the players in real time, but it is rewarding beyond measure, especially when the shots and performances work like you hoped.

Producing wears down a different part of your bones than the other three. It is mostly non-creative problem-solving. You have to make every deal, every rental, bargain with every authority, and ease all set tensions. A crew member gets sick the morning of the shoot. You have to the find the replacement. The set you’ve secured becomes endangered while you are shooting there because of a misunderstanding with the owner. You don’t have time to find another location. You have to make her happy, for on small scale productions like this one, you can’t afford to go back. Well, not often, for getting a cast and crew together for the huge chunks of time is hard, especially when they all have families and jobs. It really makes me happy when I run into people who worked on the film or let us film in their spaces and know they feel good about being a part of it.

Talk about some of the actors in the movie. Who all did you choose?

I wrote the Salesman and Traveler characters with Rhes Low and Johnny McPhail in mind. I tailored it to how the speak and look. I have worked with them both off and on since 2003, when they acted in my second short film, October, which won Best Short Film at the first Oxford Film Festival. Johnny was just starting out as an actor back then, and it has been amazing to watch his career unfold the way it has. He has such a presence in every film I have seen him in, and I agree with his scene-stealing wife, Susan, who played the Five & Dime owner in this film, that Johnny’s work as the Traveler is his best to date, which is really saying something because he was great in Ballast and True Detective.

I met Rhes in Los Angeles in 1997 when we were both taking acting classes at the Anita Jesse Studio Hollywood and working at California Pizza Kitchen in Studio City. He always worked hard, went to auditions, and got parts. I love having him on set and not just because of our friendship. Having someone with his experience in the room sets an example and a tone for everybody else. He’s a real pro even though he retires from acting from time to time.

I am proud to say that this film is the second time I have brought him out of a hiatus, the first being in 2008 when he helped Barton Segal and me make Mantis Rhes. I thought his work in this film was his best work to date. I am not surprised he has won Best Actor at two festivals so far. I hope he keeps working in films. Especially mine.

I knew I wanted the Salesman to have a family history that I could reveal in photographs set up around his home. It just so happened that Rhes Low and Jennifer Pierce Mathus had played husband and wife in three or four films previously, so by casting her, I had a collection of pictures of them from those other films that I could build on. In the film, they have a daughter who we see when she seven years-old and again when she is fourteen. Miriam Wicker’s daughter, Laura Lovelady and her cousin Addie Wicker are seven years apart and look alike, so they became Carlene. I cast Laura’s real grandmother, Lenore Hobbs, as the Salesman’s mother, which meant I could use real family pictures in the house.

There is another family in the story that the Salesman daydreams into existence. Wil Cook, the owner of the Southside Gallery, had never been in a film before, but I thought he had the right kind of look for the father. I was fortunate to find a real mother-daughter acting duo in Elise and Lola Fyke. I cast my friend Michael Weldy’s son, Lamar, to be the boy.

We needed a strong presence to play the Sheriff. I couldn’t think of anybody but Ace Atkins, who swung by the hotel before a trip to Los Angeles. A real news person was cast to play the meteorologist. She was going to film her scene before the station’s green screen. She got sick, so I called Micah Ginn, who stood before the green screen at the university and knocked it out for us. The man on the gas station bench was Charlie Hall. He overlooked the property in Alligator and wanted to be in the film. This worked out well because he had a great face, and we actually needed the cutaway to his close up to make the sequence work.

Then there was Susan McPhail, who I had never worked with before. There is a reason she keeps getting cast in major studio productions. She is a great actress. So is Rebecca Jernigan. The rest of the characters in the film are also part of the Salesman’s imagination. They antagonize his wife and daughter. I hired my former landlady in Taylor, Jane Rule Burdine, and Kelley Pinion to be the Whispering Women in the Grocery Store, and the Mean Girls were Addie’s friends, who met us at the cafeteria after school.

I thought this cast was a great mix of professional actors and real people. They all contributed. I hope they had fun.

“She refers to a phenomenon of moviegoing which I have called certification. Nowadays when a person lives somewhere, in a neighborhood, the place is not certified for him. More than likely he will live there sadly and the emptiness which is inside him will expand until it evacuates the entire neighborhood. But if he sees a movie which shows his very neighborhood, it becomes possible for him to live, for a time at least, as a person who is Somewhere and not Anywhere.” –Walker Percy, The Moviegoer

1 thought on “Get Carried Away at the Drive-In Sunday, August 16: Local Filmmaker Thad Lee Presents a New Film Based on a Stephen King Short Story”