“Smile at trouble and walk on by.”-Eric Deaton

This review was originally published in The Local Voice #94½ – December 3, 2009.

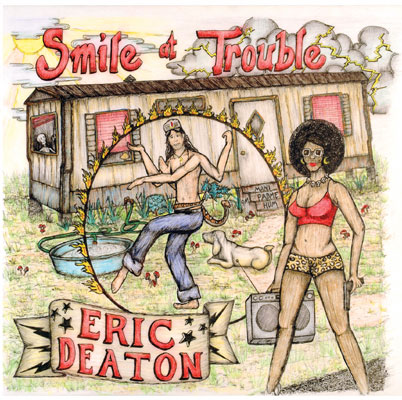

OXFORD, MISS. (TLV) – Expect more than a typical blues record when you listen to Eric Deaton’s latest effort Smile at Trouble. Your first clue is the sort of Hindi/hillbilly hybrid scene on the front cover: a multi-armed figure (think a cross between some guy getting arrested on Cops and the Hindu god Shiva) with a snake wrapped around his waist and the Sanskrit mantra “mani padme hum” written of the steps of a trailer.

The next hint that Deaton is up to more than just the blues comes on the first track, “Alap,” a droning Indian-inspired instrumental. Twangy strains of the sitar are right at home with Deaton’s achy refrain: “I’m so tired of cryin’, things are lookin’ up at last.” His use of a shruti box, a simple Indian hand-pumped instrument, provides the rich droning tapestry he weaves throughout the album.

In “Marrakesh Moan” he offers the line that gives the album it’s name: “Smile at trouble and walk on by.” This track, like the others, pulses fluidly, languidly marrying the sounds of the East and the West. Similarly, the instrumental “It Must’ve Bentonia” manages to be distinctly southern as well as otherworldly.

Somehow the juxtaposition of these seemingly dissimilar forms of music works beautifully, inspiring listeners to consider the possible connections between the Blues and Hindu music. Both the Blues and Hindu music (which is mostly songs of praise and devotion to one of the millions of deities) are steeped in age-old mythology: from Robert Johnson’s devil in “Crossroads Blues” to Hindu songstress Mirabai’s passionate odes to mischievous god Shiva.

Whatever Deaton’s reasons or inspiration for this album, it’s so interesting (and refreshing) to hear the Blues paired with a genre other than rock-n-roll. Produced by Jimbo Mathus with assistance from Deaton and Justin Showah, the album was engineered at Delta Recording in Como and mixed by Winn McElroy at Money Shot in Water Valley. Mathus and Showah also play on the album along with Kent Kimbrough, Tyler Rayburn, and Charles Gage.

Equal parts Indian drone and Hill Country moan, Smile at Trouble gives Deaton’s already impeccable musical sensibilities a new depth and resonance.

Order Eric Deaton’s compact disc, Smile at Trouble, at HillCountryRecords.com.

__________________________________________________________

A Brief History of the Shruti Box

The origins of the shruti box can be traced back to the Chinese sheng, an ancient wind instrument still in use today, which makes sound when air passes through small bamboo reeds. These freereeds were later to influence a new family of Western instruments, including the harmonica, accordian, and harmonium.

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (1723-1795), Professor of Physiology at Copenhagen, was credited with the first free-reed to be made in the Western world after winning the annual prize in 1780 from the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg. The new metal reeds were used in the harmonium, a foot-operated bellows instrument invented in Paris in 1842 by Alexandre Debain. The harmonium proved to be very popular in small chapels and churches as it was smaller and much less expensive than the pipe organs of the day.

A later version of the harmonium was developed which enabled the bellows to be operated by hand, and which featured a smaller keyboard and less stops (the small knobs pulled out to create a sustained note). This lighter, more portable instrument was taken by travellers to India where it was adopted by the native musicians and further refined to suit the folk and classical music styles. The keyboard was finally removed to make a new, smaller instrument designed solely for the purpose of producing sustained notes and chords to accompany singers and musicians.

It was called the sur-peti and later became known as the shruti box. In the 1960s travellers to India began bringing shruti boxes back to the West. The poet Allen Ginsberg was one of the earliest well-known players to use it to accompany his poetry readings. Since then the shruti box has slowly crossed geographical boundaries and musical genres to become a true world music instrument