As a signature herb, bay laurel has no peers. The leaves of this tree have not only adorned the brows of kings, but they have also provided a savory and aromatic stamp to mankind’s foods for thousands of years.

As a signature herb, bay laurel has no peers. The leaves of this tree have not only adorned the brows of kings, but they have also provided a savory and aromatic stamp to mankind’s foods for thousands of years.

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis, of course) wears the crown in the laurel family’s royal culinary heritage, but two of its close American cousins can claim coronets at the very least. The first of these is the red or swamp bay (Persea borbonia) that grows all along the Gulf Coast. Before the advent of imported bay, swamp bay brought the essence of laurel to our regional cuisine, but is largely neglected now. The American cousin of L. nobilis that deserves a more senior status in that branch of the family is sassafras.

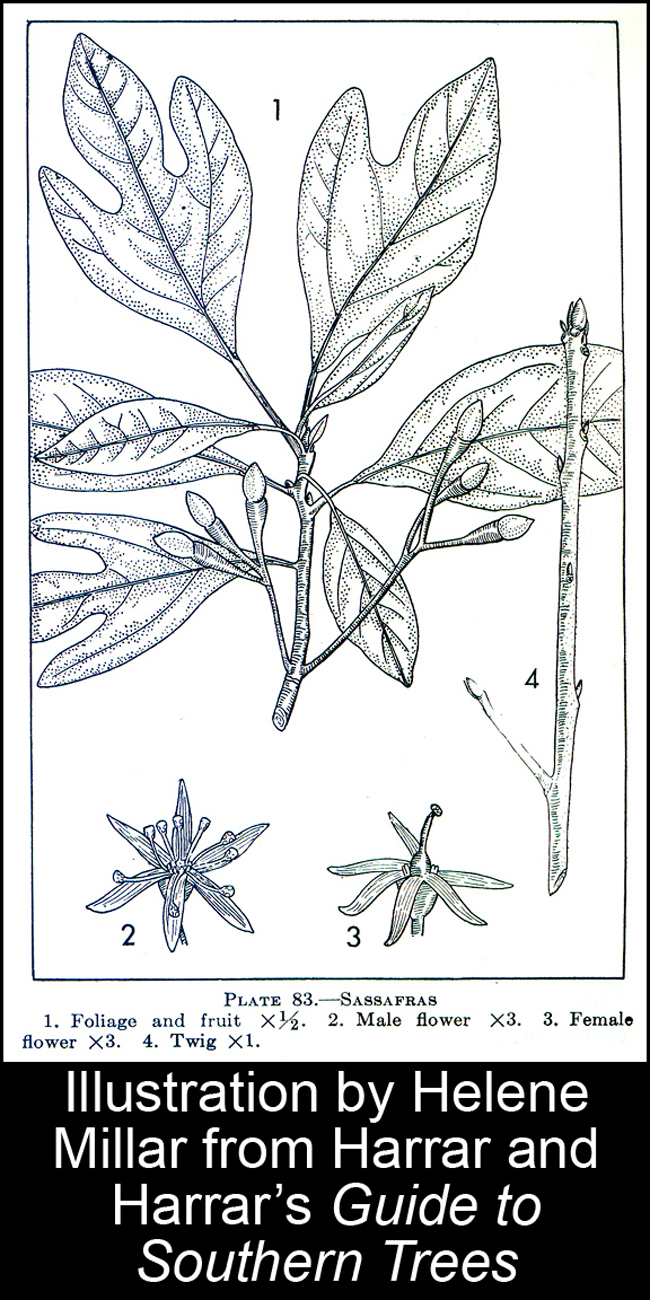

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) is the most widely-known laurel my part of the world, that being the American South. Heather Sullivan, curator of the herbarium at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, said, “Both older and younger trees have the aromatic oils that are associated with this family, which you can generate by either scratching the bark on the younger trees or cutting the bark of the older trees.”

Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) is the most widely-known laurel my part of the world, that being the American South. Heather Sullivan, curator of the herbarium at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, said, “Both older and younger trees have the aromatic oils that are associated with this family, which you can generate by either scratching the bark on the younger trees or cutting the bark of the older trees.”

“In March, sassafras bear tiny yellow flowers grouped in clusters, and appear before the leaves emerge. When the tree is in leaf, sassafras is one of the easiest trees to identify, as it usually has three different leaf shapes: a mitten, a glove, and a solid leaf, which are spicy and aromatic when crushed.”

Sullivan said that a large sassafras might reach two feet in diameter and 80 feet in height. “The tree has not had much use in modern landscaping,” she said, “which is unfortunate, because the fall color is a party of reds, oranges, yellows, and browns.”

She also adds that sassafras “is familiar to many older residents in the state,” (thanks, Heather), but given my hillbilly ancestry, I find it appropriate that sassafras became familiar to me very early in my life as an ingredient for a tea that was used as a spring tonic. According to The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Cookery (a must-have for any Southern kitchen library), roots and twigs gathered in the spring are washed, pounded to a pulp and boiled, then strained and sweetened. A little later on, I found out about sassafras beer (call it fate), and even later found out that it’s an ingredient of sarsaparilla, too.

Now, a quick caveat of sorts; sassafras oil, derived from the roots and bark, is a main source of safrole, a phenylpropene also found in cinnamon, black pepper, nutmeg, and basil, that was banned by the FDA because of its carcinogenicity in lab rats. Safrole is also classified as a List I chemical by the USDEA because of its role in the manufacture of MDMA (ecstasy). But you know what? I wouldn’t worry about it too much; it’s been proven that safrole is about as dangerous as the limonene found in orange juice and the caffeic acid found in tomatoes, and I’m damn sure not going to give up eating tomatoes on account of lab rats. I still don’t drink orange juice.

Naturally, I grew up listening to Hank Williams, and while I knew all about lost highways early on, it took me many years to discover that the filé gumbo he sings about is made with powdered sassafras leaves, which is exactly what filé is. The word “filé” is the past participle of the French filer, meaning “to spin thread,” and that’s precisely what filé does when added to a hot pot of gumbo, binding the liquid, thickening it and adding the essence of bay. Of course, you’re also going to have a few L. nobilis leaves in there as well (preferably fresh, of course; it does grow here in central Mississippi with shelter from the very coldest conditions). Sassafras adds a pungency all its own, robust and heady.

Given that sassafras is the definitive American laurel, you should not be surprised to learn that filé was used as a thickening/seasoning agent in potages long before gumbo came along. In Spirit of the Harvest: North American Indian Cooking by Beverly Cox and Martin Jacobs, the authors cite an article in the 1929 edition of The Picayune Carole Cookbook explaining that filé was first manufactured by the Choctaws in Louisiana.

“The Indians used sassafras for many medicinal purposes, and the Creoles, quite quick to discover and apply, found the possibilities of the powdered sassafras, or filé, and originated the well-known dish, Gumbo Filé.” They also add that though the Picayune was on the right track when crediting the Choctaw with filé, “it might have gone a bit further in crediting them with the invention of gumbo and the general use of powdered sassafras in cooking.” After all, “if the Choctaw had not set the precedent, it is doubtful that even the intrepid Creoles would have used a medicine to thicken their stews.”

Even after the rest of us got here and cultivated okra, filé remained an essential element of what came to be known as gumbos. Both filé and okra render a liquid thicker by means of strands of gelatinous (if not to say mucilaginous) substances I can’t even begin to describe, and for this very reason, they should be used sparingly together. Okra takes to stewing, but filé does not. If you’re using filé as a primary thickening agent, use a little in the last few minutes, and then offer a small bowl around the table for dusting.

Filé is available in most supermarkets, but look at the label. If it doesn’t say “sassafras,” don’t buy it. A far better option is to make your own, which is easily done by finding a tree and gathering the young summer leaves (under a full moon, of course). Dry them, crush them, and then put them through a fine sieve. Store as you would any powdery substance. You know the drill.

–

This article was originally printed in The Local Voice #201 (published April 3, 2014). To download a PDF of this issue, click HERE.